Spreading the word – sixteenth century-style

It is believed to have begun with Martin Luther posting his Ninety-Five Theses to the door of the Wittenberg Castle Church, in northern Germany, and it changed the face of sixteenth century Europe, splintering Western Christianity and paving the way for individualism, scepticism, civil rights, capitalism and modern democracy.

But how did the Protestant Reformation – one of the last millennium’s defining moments, overturning the centuries-long religious and political domination of the Roman Catholic Church – gain currency among Europe’s common people?

Many historians have focused on the invention of the printing press, which enabled inexpensive copies of the Theses to be widely circulated, along with pamphlets attacking the Church and conveying the Reformation message.

The vast majority of the largely rural population was, however, illiterate. So pioneering Australian social historian Robert Scribner looked for alternative explanations for how these revolutionary ideas were spread and adopted in Germany. His research from the 1970s uncovered the powerful influence of imagery, songs and plays, street and saloon bar preaching, and communal rituals and festivities, both civic and religious.

Charting a social movement

Scribner’s work, highlighting the role of popular culture and religion, including folk beliefs and traditions, revolutionised our understanding of how the reformers won over the masses, still deeply attached to Catholic practices even if they despised the corruption of some of the church hierarchy and its institutions.

Scribner did his undergraduate and Master’s degree at the University of Sydney, and although he held academic positions in the UK and, latterly, at Harvard, he maintained close connections with, and assisted, Australian scholars and students, some of whom conducted research and gained appointments in Europe. He also returned to Australia to attend conferences and deliver public lectures and seminars, influencing the direction of Australian scholarship on Reformation and early modern European studies.

With Scribner’s emphasis on the Reformation as a social movement, not just a momentous event in the history of Christianity, he transformed the fields of Reformation studies and early modern European history.

Songs, picture books & chats at the pub

His focus on the wider social and cultural context grew out of historians’ new interest in common people as valid subjects of study.

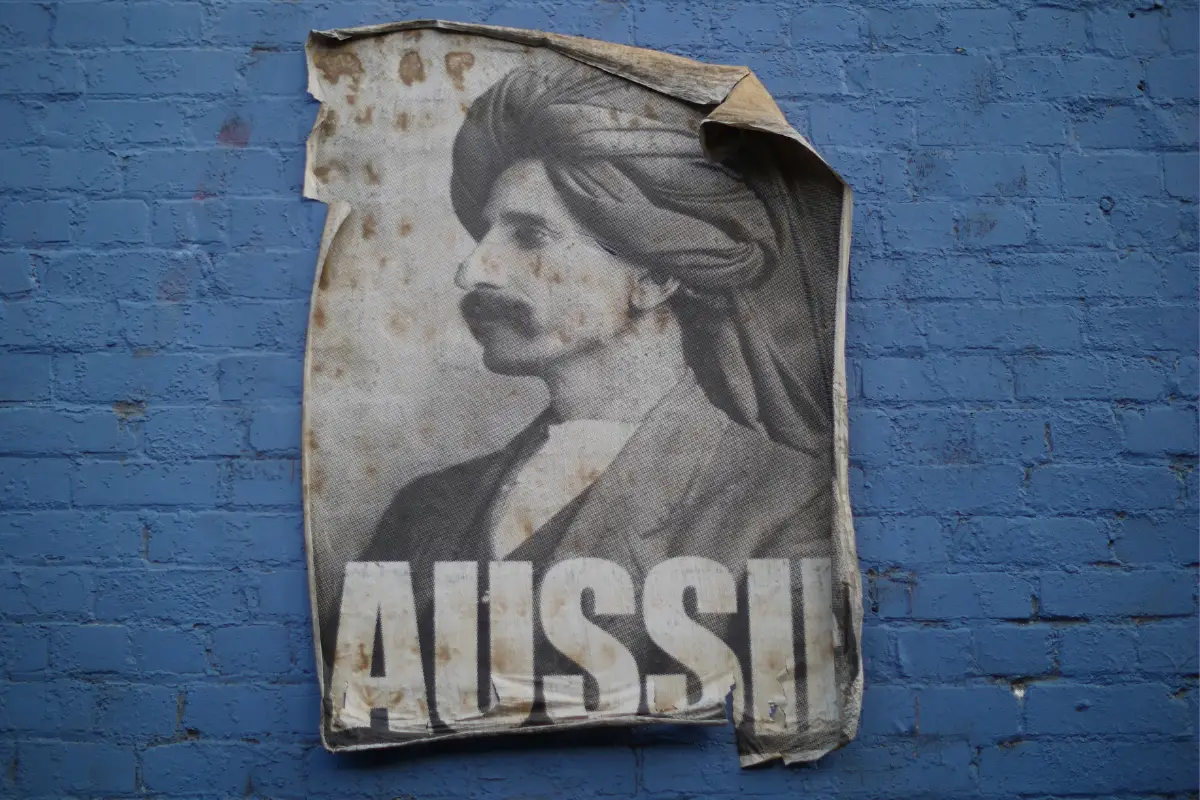

In his first, widely acclaimed book, For the Sake of Simple Folk: Popular Propaganda for the German Reformation, Scribner provided the first detailed analysis of how Protestant teachings were transmitted through polemical imagery, including book illustrations, picture books and woodcut images printed in popular “broadsheets” (single sheets sold by street vendors), many of them satirising the Pope and the clergy.

He also identified the importance of oral communication, with pamphlets read aloud or sung by more literate opinion-formers, and the new faith discussed in public forums such as pubs.

One of the few Western researchers to comb the East German archives in the 1970s, and drawing on the insights of anthropology, social and visual history, media and performance studies, he unearthed stories demonstrating how Reformation ideas appealed to different groups and were disseminated in different ways.

The German carnival, or Fastnacht, for instance, with its ritualised public displays, helped to fuel criticism of the Church and shape the Reformation as a popular protest movement, engaging people not primarily interested in complex theological arguments.

Acording to fellow Australian Reformation historian Lyndal Roper, Regis Professor of History at the University of Oxford, Scribner

“turned Reformation history on its head … He made it his business to debunk all the comfortable Reformation myths.”

His focus on visual media led to closer relationships between academic researchers and cultural institutions, and his work showed the power of culture in bringing about societal change, thereby making an important contribution to the newly emerging field of cultural history.