As news of the stabbing of Salman Rushdie reverberates around the globe, speculation in the Western press about what this violent act signifies and why it has occurred has intensified. How did Hadi Matar, the 24-year-old alleged assailant, access the stage so easily? What insights can be gleaned from Matar’s social media history, which suggests an interest in ‘extremist Shia causes’ and Iran’s Revolutionary Guard, or from his Lebanese heritage?1 Why did the event’s organisers fail to provide sufficient security measures, given the fatwa against Rushdie remains in place? Why did they disregard the violent history that has shaped Rushdie’s career since the publication of The Satanic Verses in 1988?

In an interview in 2019, Rushdie seemed to dismiss the fatwa as a live threat, expressing an understandable desire to be free of the decades-long fear of violent reprisal: ‘We live in a world where the subject changes very fast. And this is a very old subject. There are now many things to be frightened about – and other people to kill.’2 This assurance seems to be naïve in hindsight, given that the bounty on Rushdie’s head was increased as recently as 2016, and the fatwa reinforced by Abbas Salehi, the then Iranian deputy minister of culture and Islamic guidance, who proclaimed: ‘Imam Khomeini’s fatwa is a religious decree, and it will never lose its power or fade out.’ Salehi’s statement is currently being cited in press coverage and commentary alongside brief histories of the protests and riots that broke out in India and Pakistan in 1989, the banning of The Satanic Verses in multiple countries, the death or injury of various associates of Rushdie over the years, and the bombing of bookshops in the US and UK.

There are many aspects of this tragic event and the media coverage it has inspired that are striking to a researcher, such as myself, who has spent the last five years researching the complex and enduring relationship between rioting and literary writing. Here are just a few:

The event organisers’ defence of their decision not to install metal detectors or conduct bag checks at the auditorium doors tells us a lot about our collective investment in literary events (festivals, lectures, book launches) as spaces that are antithetical to violent disruption in any form. Channelling this belief, Michael Hill, the Chautauqua Institution’s president, responded to criticisms that audience members were checked for food but not for weapons, by strenuously demarcating the space of the literary event, and by implication of the literary sphere, as one of inclusive creative humanistic inquiry free from censorship and intolerance.3

Admirable though these sentiments are, they fail to acknowledge that part of the allure of Rushdie as a guest is the history of riots, protests, and censorship that have shaped his writing career since the publication of The Satanic Verses.To pretend otherwise is to discount the increasingly volatile literary and political worlds that contemporary writers, such as Rushdie, must navigate.

To quote Indian author Salil Tripathi speaking on behalf of PEN International of his hope that major publishers will continue to publish The Satanic Verses: ‘I have not totally lost hope, but undoubtedly the Rushdie case has created a mental brake. A lot of subjects are now seen as taboo.’ In the same interview, Tripathi continued: ‘In India with Hindu nationalism, people are very wary about saying things about Hindu gods and goddesses because you don’t know what might happen to you. The threat of the mob has grown phenomenally….’4

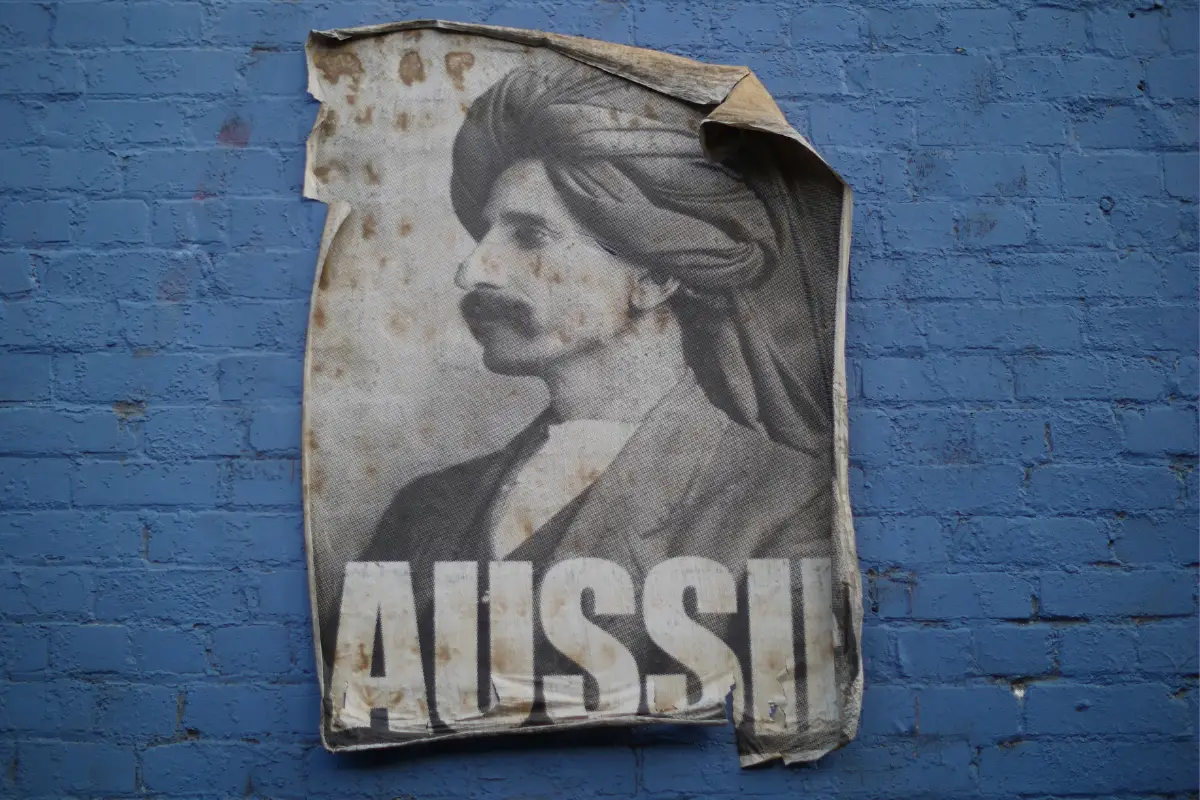

Whilst the threat the ‘mob’ poses should never be discounted, the narration of the 1989 riots in the UK and US media in recent days in the Guardian and elsewhere has mobilised the familiar polarising scenography and character types of historic riot coverage, specifically the threat posed to civil society by dangerous outside agents. In this version of the event, Matar, an American citizen of Lebanese descent, is characterised as an emissary of Iranian religious intolerance that threatens the peace and liberty of Anglo-American secular humanistic inquiry and creativity. Here the associative noise of past riots in India and Pakistan merges with allusions to Matar’s ‘Shia extremism’ to bolster familiar geopolitical divisions between a free West and a fanatical East: divisions that Rushdie has himself rejected, whilst strongly and, sometimes controversially, condemning Islamic and religious extremism.5

In his 1989 essay on The Satanic Verses, the Indian-born-American academic Srinivas Aravamudan argued that Rushdie’s satirical novel put into question the limits of Western free speech doctrine that were being mobilised in its defence.6

Accordingly, to appreciate the satirical power of The Satanic Verses, its offensiveness to the targets of its satire should not be denied or disavowed, nor its critical intervention reduced. The literary and the literal are necessarily and irrevocably intertwined in Rushdie’s case.

This returns us to the violent scene that played out on stage at the Chautauqua Institution last Friday. Such moments not only exemplify why literature’s power to criticise, incite a riot and offend must be protected, they also serve to remind us that literature’s enduring and complex relationship to political violence demands analysis that moves beyond simplistic demarcations of words and acts, literature and politics.7

References

1 Oliver Millman, ‘Salman Rushdie attack: details emerge about New Jersey suspect,’ Guardian (Sunday 14th August, 2022).

2 Julian Borger, ‘A Tsunami of outrage: Salman Rushdie and The Satanic Verses,’ Guardian (Saturday 13th August, 2022).

3 Ed Pilkington, ‘Rushdie attack prompts questions over security at New York event,’ Guardian, Sunday 14th August, 2022); see also Carolyn Thompson and Hillel Italie, ‘Salman Rushdie on Ventilator After Stabbing Attack,’ Time, August 13, 2022.

5 See Matthew Fellion and Katherine Inglis, ‘The Satanic Verses’ in Censored: A Literary History of Subversion and Control (Montreal: McGill University Press, 2017), pp317 – 335. Thank you to Laetitia Nanquette for this reference.

6 Notably, the chief editor of Iran’s hardline daily Khorasan, Ali Alavi, has international community for constructing the attack on Salman Rushdie as an attack on free speech. Srinivas Aravamudan, ‘Being God’s Postman Is No Fun, Yaar”: Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses,’ Diacritics 19.2 (Summer, 1989): 12.

7 This brief essay has been significantly improved by the generous feedback of Jumana Bayeh, Laetitia Nanquette, and Sean Pryor.