Tensions between indigenous and settler history are not restricted to white, Western countries. Throughout most of Asia, indigenous peoples dominate the construction of national narratives, and in many cases, they have weaponized them to marginalise minority peoples – both the descendants of immigrants and also other indigenous peoples.

In Singapore, however, the indigenous peoples (Malays) are in a minority, albeit a much larger minority than that of Australia’s Indigenous peoples: 13.5% of Singapore’s residents are Malay in a mostly migrant population dominated by ethnic Chinese (74.3%).

Despite many differences between the experience of settler colonialism in Singapore and Australia, there are several important similarities, including in the indigenous people’s measurable disadvantages in economic and educational indicators.

The marginalisation of Singapore’s Malay indigenous history and identity is also evident in the school History curriculum. Yet, in this matter, we find a surprising difference with the history curricula devised in white settler colonies like Australia. The marginalisation of Malay history in Singapore’s textbooks marks a break – not a point of continuity – with the colonial educational record.

British Malaya (which effectively included Singapore until the mid-1950s) was a Malay-majority colonial ‘nation’, and it suited the colonial authorities to promote British-friendly Malay nationalism. The Singapore History curriculum joined the Malayan curriculum in following this Malay-friendly agenda from Malaya’s independence in 1957 until after 1965 – the year that the Chinese-majority territory of Singapore broke away to establish the independent Republic of Singapore.

Singaporean independence was preceded by a year of vicious political campaigning that was mostly framed in terms of ethnic hostility between Malays and Chinese; hostility that drew in turn upon older, colonial-era stereotypes of ‘lazy natives’ and ‘greedy’ Chinese. Singapore’s regard for its Malay community has never fully recovered from this rocky start – a reality that is starkly visible in the subsequent evolution of the History curriculum being taught in schools.

Rejecting the first draft

The first attempt to reconstruct the History curriculum in independent Singapore excluded the Malay community from the national narrative so forcefully that Malay politicians burnt copies of the accompanying textbook in protest. It seemed that the ethnic Chinese academics, who spent several years working on the draft, preferred to give credit for Singapore’s achievements to the British colonisers and their Chinese business partners rather than acknowledge Malay contributions, either before or during colonisation. Local Chinese newspapers took a different slant to both groups. They expressed mild resentment for having to share credit with Singapore’s British colonial ‘founder’, Sir Stamford Raffles.

The reception of the new History curriculum proved to be so divisive – and so distracting for the government’s developmentalist agenda – that the government cancelled all schoolroom teaching of local and national history in 1972. Then, in 1977, a new, nationalist history, written by an expat English historian named C.M. (Constance Mary) Turnbull, turned an exciting new page in Singapore historiography.

Turnbull’s A History of Singapore, published by Oxford University Press, provided solid scholarly credentials for a modernist, nationalist template that appealed to both the Chinese majority and the developmentalist People’s Action Party (PAP) government, led by Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew. It was an exceptionally thorough archive-driven history, but because the records it drew upon were entirely sourced from colonial archives, it told a British colonialist story. Turnbull’s nationalist perspective was genuine and forceful, but it expressed itself mainly in her vigorous exploration of the contributions of ethnic Chinese as the colonialists’ business partners and labour force, and her depiction of PAP politicians as nationalist heroes who were launching independent Singapore on a path of peace and prosperity. Indigenous peoples were almost completely absent.

A revised curriculum dismissing pre-colonial history

In 1984, the government introduced a fully revised History curriculum for schools. It included two compulsory years of Singaporean history, explicitly using Turnbull’s book as the template. In this iteration, Singapore’s history began with the arrival of Raffles in 1819, and five centuries of well-documented pre-colonial history were dismissed as irrelevant. During that half-millennium, Singapore had been an important naval and trading port in two Malay empires and a contested strategic prize in both intra-Asian and Asian-European imperial rivalry that appeared routinely in both Chinese and European records.

The curriculum also denied Malays a role in Singapore’s colonial achievements – thus ignoring the critical role of the ancestors of the present Sultan of Johore, who ran their hugely successful businesses from their palace in Singapore until 1889. This family arguably saved the colony from complete failure in the 1840s – when it faced a near-perfect storm of existential threats – and thereafter emerged as one of Singapore’s (and Johore’s) most important Asian business families. It played a central role in Singapore’s developmental history in the second half of the 19th century, but, in the history curriculum of 1984, it is invisible.

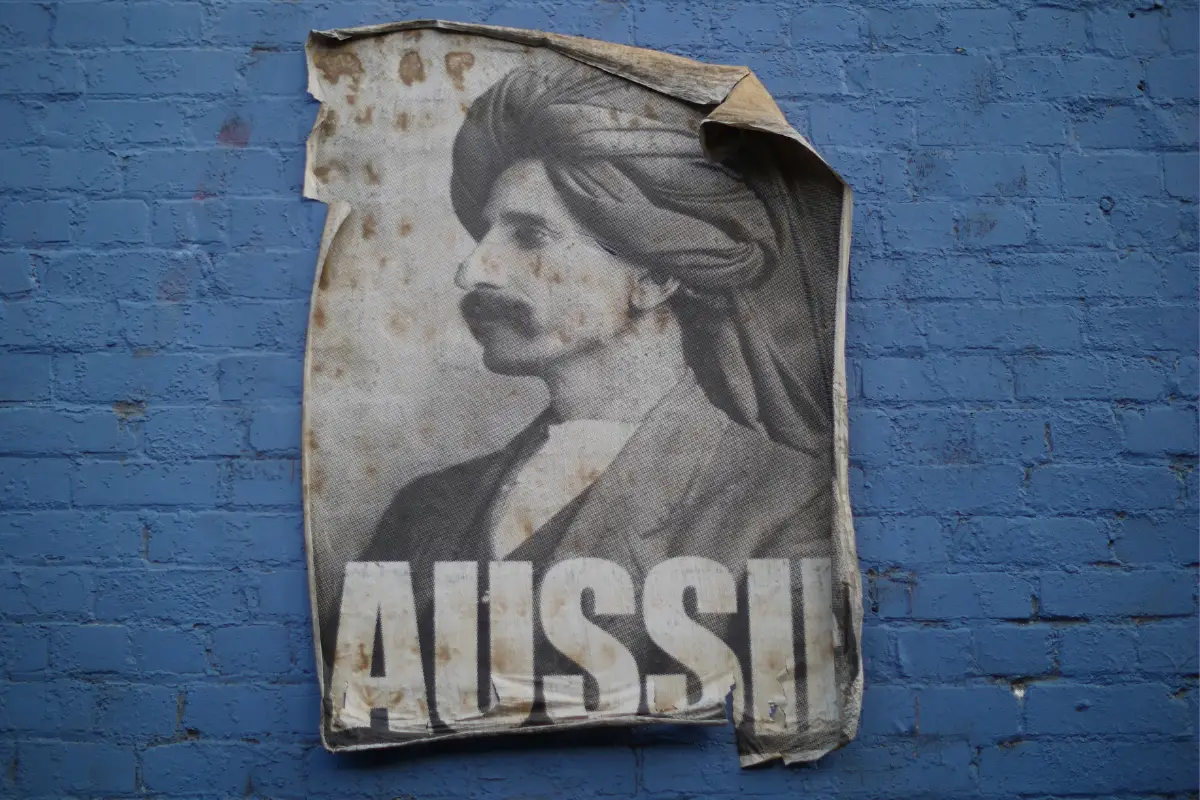

The exclusion of Malays was even more thorough in the new History textbooks than in the curriculum, extending to their near-absence in the selection of photographs and personal stories, and the inclusion of a highly offensive chapter that disparaged Malay claims of indigeneity.

The 1984 curriculum remained almost unchanged until 1996, when Turnbull’s version was overlaid with Lee Kuan Yew’s personal story. Turnbull’s book remained the foundation, but the first volume of Lee Kuan Yew’s soon-to-be-released memoirs replaced A History of Singapore as the main resource. In 1996 Lee Kuan Yew was portrayed as a second Raffles; a second ‘father of the nation’.

The ongoing fight to include pre-colonial indigenous history

This record of largely obliterating Malay contributions to Singapore’s history makes it somewhat surprising that any serious revision of the History curriculum has occurred at all. Efforts to include pre-colonial indigenous history have been due to a combination of academic pushback against Lee Kuan Yew’s overreach in the 1990s, the advent of new revisionist scholarship (mostly by non-Singaporeans) that could no longer be ignored, and the patient activism of a handful of Singapore-based historians in a position to advise the Ministry of Education on curriculum matters.

The first fruits of these efforts appeared in the 2006 version of the curriculum, but progress has been slow – and the latest textbook produced in 2021 is a step backwards, offering less coverage of indigenous history than the previous iteration. It is nevertheless clear that there is little chance of a return to the status quo ante – pre-colonial indigenous history is here to stay.

There has not yet been any acknowledgement of Malay contributions to the success of colonial Singapore, but I live in hope.

About the author

Michael Barr FAHA is an Associate Professor of International Relations (Academic Status) at Flinders University. He is the author of five monographs and the co-editor of two books on Singapore politics and history. This article is derived from a series of three recent publications (two refereed articles and one book chapter) on History education in Singapore.