1969, Australia. More than two decades of conservative rule was nearing its end and the Nation was undergoing rapid social and cultural change following a lengthy period of post-war migration. Australians were making their mark overseas in arts, culture, media and performance.

At home, humanities scholars were conducting ground-breaking research, including the discovery of the oldest-known burials of the First Australians at Lake Mungo, new work on the foundations of Australian literary culture, and the beginning of a blaze of scholarship on women’s history, all with unfolding and ever-changing significance for the understanding of Australian character and experience. Across the country, university enrolments in the arts and humanities outstripped even those in science and technology.

The Academy's beginnnings

The idea of an Academy was first floated by Sir Robert Menzies—the Nation’s longest serving Prime Minister— with his ill-fated plan in the 1930s to create an Australian Academy of Art. It was an idea well ahead of its time, but it was one this politician on the rise would never let go. Some 20 years later, Menzies was still advocating for the importance of ‘humane studies’ writing in an Australian Humanities Research Council (AHRC) publication The Humanities in Australia that:

‘We live dangerously in the world of ideas just as we do in the world of international conflict. If we are to escape this modern barbarism, humane studies must come back into their own, not as enemies of science, but as its guides and philosophic friends…Wisdom, a sense of proportion, sanity of judgement, a faith in the capacity of man to rise to higher mental and spiritual levels; these were the ends to be served by the Humanities Council.’

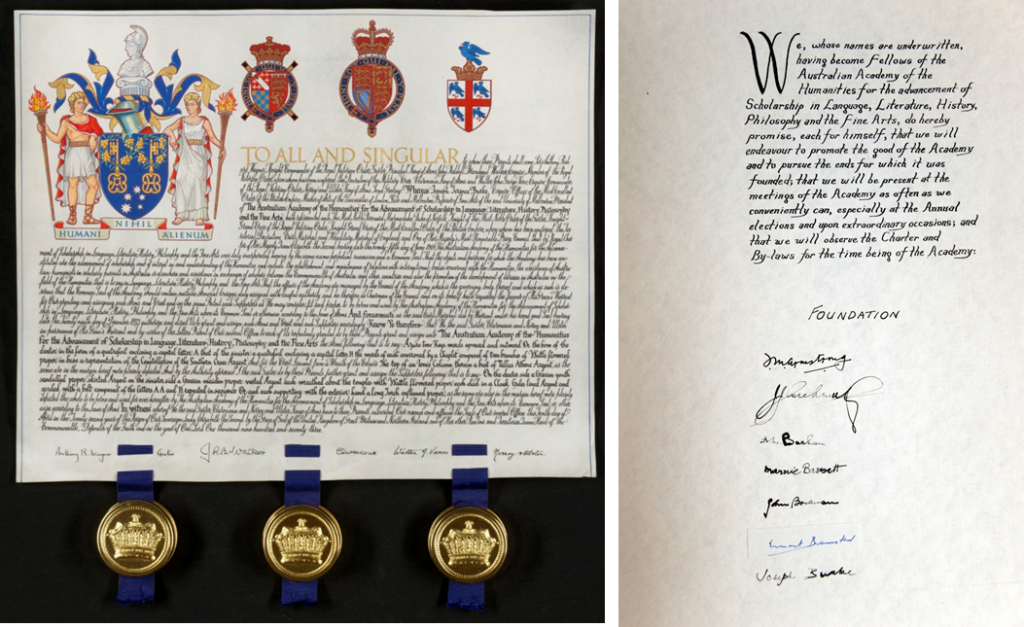

While Menzies provided the political will and momentum for the creation of the new Academy, it was two of our most distinguished historians, Sir Keith Hancock KBE FBA FAHA and Max Crawford OBE FAHA, whose combined efforts gave rise to the Academy’s creation in the late 1960s and who acted as its tireless sponsors in the world of academia. Crawford was the immediate past president of the AHRC, the entity which would eventually be transformed into the Academy. Crawford had carefully steered the Council along its path towards Academy status, culminating in its founding by Royal Charter by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, on 25 June 1969. In so doing, he provided a platform for a new era of prosperity in the humanities and its disciplines.

Those early years of the Academy weren’t without their challenges, particularly in the selection of those considered worthy to be amongst its new Fellows. Nonetheless, Hancock, who had become the new Academy’s first President, was jubilant in his letter to the by then former Prime Minister Menzies, celebrating that achieving Academy status meant:

‘The phoenix has now risen from its ashes, a lovelier bird and – what matters more – a livelier one. We have not only a new name but a new infusion of creative vigour.’

The first fellows

At its beginning, the 51 Members of the Australian Humanities Research Council which included poet A.D Hope and historians Kathleen Fitzpatrick and Manning Clark became the Foundation Fellows of the new Academy. By the next year, 16 leading scholars were elected as the first intake of Fellows, including historian Geoffrey Blainey and and archaeologist John Mulvaney. The work of the Academy at this time centred on promoting excellence in the humanities through annual events, supporting younger scholars and providing support for the publication of high-quality humanities research.

Our Fellowship today

Today, the number of Academy Fellows has grown to over 620 distinguished scholars and public intellectuals in the Humanities disciplines spanning culture, history, languages, communication studies, linguistics, religion, philosophy and ethics, archaeology and heritage. The list is a veritable who’s who of the nation’s humanities leaders and includes Honorary Fellows Robyn Archer, Kate Grenville, Barry Jones, Michael Kirby, and Alexis Wright, just to name a few.

Our Fellows are the lifeblood of the Academy’s endeavour to promote excellence in the Humanities. Individually and as a collective they lead Australia’s vibrant humanities community of scholars and practitioners. They are a constant, ever-present force in helping us all understand our past and make sense of the present, and they demonstrate how crucial the Humanities will be in ensuring a humanised future.

On the occasion of the Academy’s 50th anniversary, we invited a number of eminent Australians—Honorary and Corresponding Fellows of the Academy—to share some thoughts on the past, present and future of the humanities and to reflect on what is really at the heart of the Academy’s motto—Humani nihil alienum —part of a line from the Roman writer Terence, meaning “nothing that is human is alien to me.”

Our future

The Humanities remain as vital to our Nation today as they were at the creation of the Academy in 1969. The Humanities are the drivers of social change and awareness, record keepers of our past and present and are the creative and human face of innovation and progress.

The work of the Academy has now advanced to providing independent and authoritative advice—including to government, industry and the education sector—to ensure ethical, historical and cultural perspectives inform discussions regarding Australia’s future challenges and opportunities. We also play a unique role in promoting international engagement and research collaboration.

As in the 1960s, university enrolments in the Humanities, arts and social sciences remains strong, just over 60%. The Academy’s long-standing and extensive grants and awards programs invest in the next generation of humanities researchers. You only need to see the breadth and depth of work led by our 2019 Crawford Medallist and Travelling Fellowship, Publication Subsidy Scheme recipients to see the vibrancy of Australia’s emerging humanities leaders.

With many new challenges and opportunities facing the Nation including emerging technologies and artificial intelligence, international conflict and diplomacy, and shifting trends in how we engage with and support arts and culture, the Academy has articulated a vision for a ‘humanised future’.

This requires a human-centred approach to all that we do in government, industry, education and the community. As a result, we will ultimately experience a future with a human focus – one that is marked by inclusive and diverse workforce strategies, responsive natural and cultural resource policies, ethical digital transformations, thriving and sustainable creative and cultural industries, and cohesive, strong, tolerant communities.