The panelists were Associate Professor Andrea Gaynor, Dr Blanche Verlie, Dr Tom Ford and Dr Paula Satizabal.

Dr Verlie began by describing the ‘emotional intensity’ experienced by herself and her students when focusing entirely on the impacts of climate change for a whole semester.

‘In this era of climate change, thinking relationally about it can be really distressing’ said Dr Verlie. ‘It brings to bear just how much we are both not in control of the situation, even though we might have significant influence on it, and also how vulnerable we are to those changing relationships.’

She outlined her team’s latest research findings, the result of surveying Australian environmental educators about their experiences of, and strategies for, responding to their students’ ecological distress. Discussed in her recent co-authored article ‘Educators’ experiences and strategies for responding to ecological distress‘ Verlie’s approach of engagement, validation, support and empowerment provides an essential framework for helping students think about their own response to the crisis.

Associate Professor Andrea Gaynor observed that many of her students are yet to reach the ‘ah ha’ moment, ‘where the reality of climate change, the reality and the seriousness of the situation we’re in, hasn’t quite sunk in.’

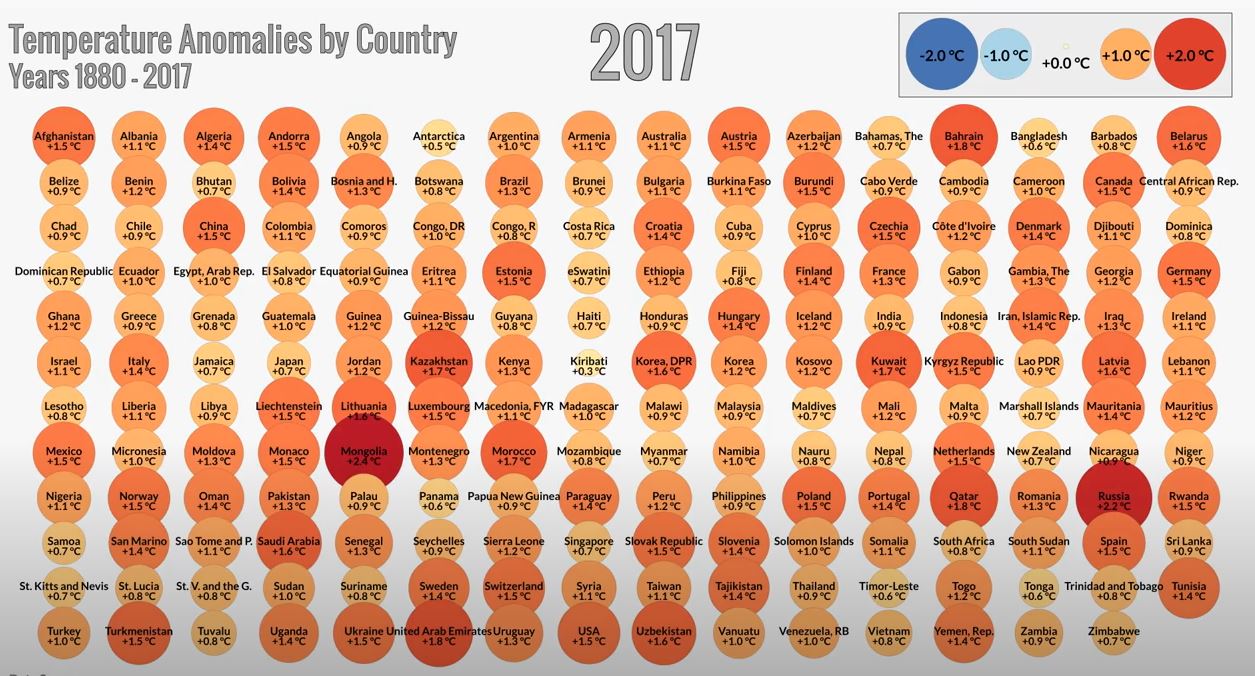

She discussed her use of a stark visual representation (see Fig.1) of the temperature anomalies in different countries from the 1900s to the 21st century as an evidence-based tool for introducing students to the extent of climate change and reiterated the importance of stories in educating students about both the crisis itself and our management of it.

‘It’s important to inspire students by introducing them to a world of stories’. These include stories about disaster, about resilience, environmental wins; stories about the changing relationship between people and the non-human world to show how things can be different, and stories that build the sense of a shifting moral universe, encouraging students to position themselves as ethical actors in the moral world that we currently inhabit.

Dr Tom Ford then shifted the focus of the discussion to institutional challenges, lamenting the loss of resources across departments which will likely have halved by the end of this year from when he started just 18 months ago.

‘The business models of the university systematically preclude the type of reflective teaching called for by Nigel Clark – teaching that sees in the relationship between teacher and student an opportunity for ethical action’ he said.

‘Nigel Clark’s statement is not bleak enough. His word ‘unavoidable’ should be replaced with something like ‘impossible’. Bearing witness to the loss of something we love is an impossible part of teaching, for it is blocked by the institutions in which we teach,’ Dr Ford added.

Dr Paula Satizabal also picked up on the theme of loss and survival, pointing out that we must learn from those who are willing to share their stories of enduring and overcoming major crises.

‘In dealing with loss it is vital to listen to those working with us who have already survived apocalypses, highlighting those First Nation and Indigenous people who are still here after surviving the impact of colonisation,’ Dr Satizabal said quoting Natalie Osborne’s 2019 essay ‘For still possible cities: a politics of failure for the politically depressed’.

She said an important part of her survival in this challenging world came through the creation two years ago (pre-pandemic) of a group of early career academics who meet informally to share their experiences and learnings.

‘We chose storytelling as a political act, inspired by Indigenous scholars and thinkers. Through our storytelling we have noticed how difficult it is to articulate and share painful and embodied memories of loss.

‘Yet our storytelling helps us make sense of our unique and shared experiences while allowing us to build a collective memory. The pandemic has enabled us to meet on-line and to join together from different parts of the world.’

The conversation concluded with an engaging Q and A with attendees, including a discussion on the role of the humanities in helping deal with the current climate crisis, with unanimous agreement STEM can’t fix the problem on its own.

‘The word is in the title, in the name of the ‘humanities’ Dr Verlie said. ‘Environmental problems are human problems, both in their causes and their impacts. If we really want to catalyse change, the humanities have an important role to play.’

Extra resources

- Australian Energy Transition Research Plan 2021, June 2021.

- Temperature Anomalies by Country 1880-2017 (animation used in Andrea Gaynor’s presentation)

- Bowers, C.A, Education, Cultural Myths and the Ecological Crisis: Toward Deep Changes,

- Celermajer, Danielle, ‘Omnicide: Who is responsible for the gravest of all crimes?’, ABC Religion and Ethics, 3 Jan 2020.

- Ghadery, F., Abdelkarim, S. & Sen, R., 2021, ‘Collaborative Praxis: Unbinding Neoliberal Tethers of Academia’, Feminista Journal.

- Holmes, K., Gaynor, A. & Morgan, R., 2020 ‘Doing environmental history in urgent times’, History Australia.

- Hulme, M., 2020, Climate change forever: the future of an idea, Scottish Geographical Journal.

- Leimbach, T., Kent, J., Walker, J. & Allen, L. 2020, Staying sane in the face of climate change: A toolkit of emerging ideas to support emotional resilience, mental health and action [report], University of Technology Sydney.

- Pascoe, S., Sanders, A., Rawluk, A., Satizábal, P & Toumbourou,T., 2020, ‘Intervention – “Holding Space for Alternative Futures in Academia and Beyond’, Antipode Online.

- Robin, L. 2017, Environmental humanities and climate change: understanding humans geologically and other life forms ethically’, Wiley Online Library.

- Verlie, Blanche, Learning to Live with Climate Change: From Anxiety to Transformation (Routledge: 2021). Click here for free e-book version