In 1749, a socially and religiously provocative event orchestrated and performed by a group of brazen women unfolded on the streets of Damascus. It was an unprecedented celebratory pageant dedicated to the miraculous recovery of a young man from a fatal illness — he was the lover of one of the participating women.

Breaking the conservative city’s social and religious taboos, the women marched through the city’s marketplaces well dressed, wearing full make-up, and without head cover. They let their hair down and showed off their beauties. They came well prepared: some carried lanterns, some held candles, and some brought censers, yet others brought tambourins. They sang, clapped, and played the tambourins along the way, while crowds of locals lined up the streets on both sides watching, some in amazement and excitement, others in shame and disbelief. It was a love pageant the likes of which the city had never seen before.

A shameful display or a brave declaration of love?

The love pageant celebrated love openly by Damascene women at a time when Damascene men were zealously debating the legitimacy of love and lust and their religious and moral implications. The procession, which was radically daring even by today’s measures, roamed the city, terminating at the shrine of Damascus’ patron Sufi saint (shaykh Arslān), located on the outskirt of the city, where the women held a religious ceremony to thank God for the young lover’s recovery.

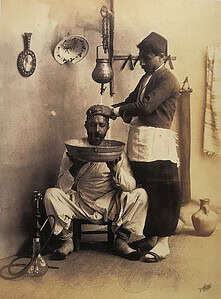

Details of the event survived in a unique diary written by a local barber known as Ibn Budayr. A commoner brought up in a religiously conservative family, Ibn Budayr identified the women as the ‘town’s prostitutes’ (shlikkāt al-balad) without giving any information about their social identities and familial connections. Although Ibn Budayr’s report of the event cannot be corroborated by other existing historical accounts, his narrative has been accepted unchallenged by Arab historians, and the depiction of these brave Damascene women as shameless and worthless prostitutes has been instrumental in characterising the period as one of decline and moral decadence.

This prevailing perception has erased this significant event from the city’s enduring memories. Many important questions have been left unanswered. Who were these remarkably daring women? To what social class did they belong? In what part(s) of the city did they live? Were they making a public statement about love? Were such pageants a common socio-spatial practice in the city? How did the Damascenes see and react to the love pageant? And what was the love pageant’s emotional impact on the city?

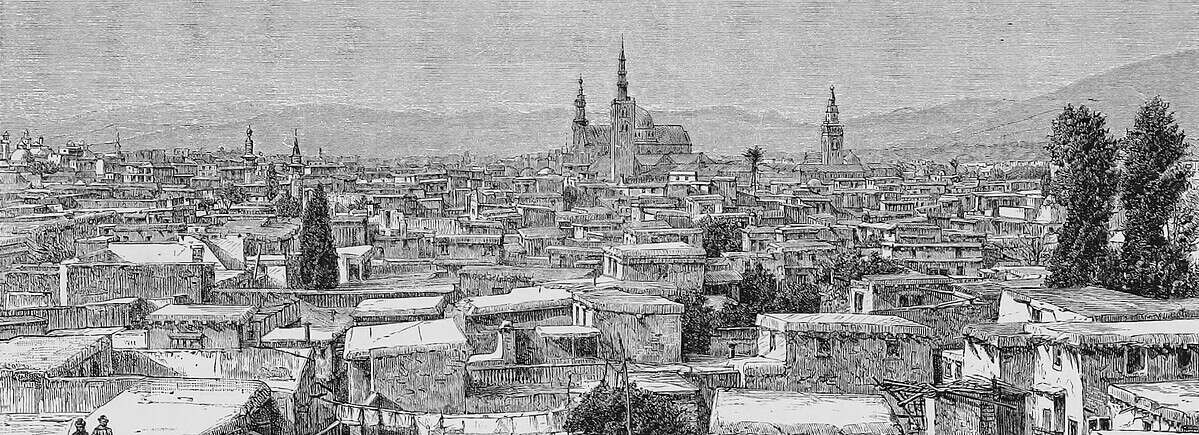

Changing social freedom of women in Damascus

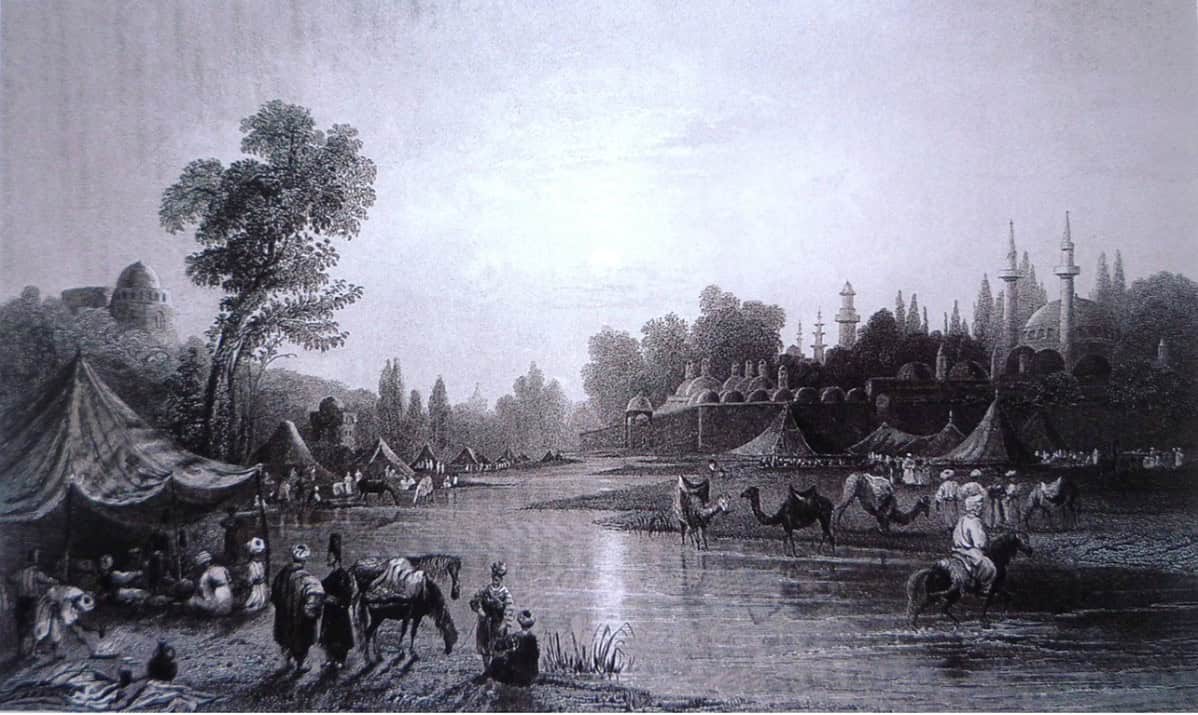

Reading through the barber’s diary reveals other exciting events. In 1750, a few months after the remarkable love pageant, Ibn Budayr writes about a joyful picnic he had with friends at the beginning of spring. The group sat in a well-known recreational area overlooking the banks of the city’s Baradā River that meanders gracefully along its beautiful valley outside the city’s protective walls.

From his elevated spot, the barber could see families and large gatherings picnicking and entertaining at the lower ground next to the riverbanks. On that day, Ibn Budayr recounts his great surprise to see ‘more women than men, sitting on the riverbank, eating, drinking, smoking, and having coffee all day long, as men usually do’. ‘This is something we have never seen’, the barber exclaimed, ‘nor anyone else before us had, until this time’.

In another contemporaneous memoir, Damascene Catholic Father, Mīkhāʾīl Brayk, shows that Christian women were also enjoying a new level of social freedom. Father Brayk spoke disapprovingly of the worrying freedom young Christian women had acquired and the increasing social openness that saw large gatherings in the city’s parks and gardens.

Now, he wrote, they could meet freely with young men, and smoke and drink coffee in public without hindrance.

He launched a scathing attack on their shameful and disrespectful behaviours that brought disgrace to the Church and the Damascene Christian community. Father Brayk also referred to the Christians’ ability to drink wine and spirit (Arak) in public during their recreational gatherings without the interference of anyone. He also tells us how Damascene Christians, both males and females, had abandoned the once enforced religious dress code and were able to wear whatever colour and cloth they like (except green). They were also able to trade freely, accumulate wealth, and show off their wealth by building large houses and extravagant palaces.

Women in public spaces

The unprecedented liberal spatial practices and daring presence of women in the city’s public spaces point to the increase social freedom and changing socio-religious character of Damascus in mid-18th century, when Enlightened Europe was experiencing similar transformations.

While being excited about the new social changes sweeping the city, both the barber and the priest were highly critical of the increased social liberty and personal freedom. Both diarists’ emotional reactions have influenced the (mis)reading of the history of the city during this period, with the majority of contemporary Arab historians taking the same emotional stance and seeing these changes as signs of moral decadence and religious decline. These hasty emotional conclusions can be easily contested by rational analyses of the accepted narrative.

Globally, new research has shown that early modern transformations were not restricted to Europe as the Eurocentric global history has held for a long time. Several Ottoman centres, including the capital Istanbul, witnessed significant cultural change. Locally, immoral behaviours were not tolerated in Damascene neighbourhoods as court records show, and ‘prostitutes’ holding a religious ceremony in the city’s most revered tomb is hardly believable. Nonetheless, the dominating collective impression of this period remains one of declining moral and religious order thanks largely to the 19th-century Arab Renaissance narrative, which — in the manner of the European Enlightenment — considered the preceding period as the darkest in Islamic history.

The article is based on the author’s Arabic book: Samer Akkach. 2015. Yawmiyyāt Shāmiyya: Qirāʿa fī al-Tārīkh al-Thaqāfī li-Dimashq al-ʿUthmāniyya fī al-Qarn al-Thāmin ʿAshar (Damascene Diaries: A Reading of the Cultural History of Ottoman Damascus in the Eighteenth Century). Beirut: Bissan. https://www.arabicbookshop.net/yawmiyat-shamiyah/244-217