The very first article in the world’s leading journal, Nature, was more poetry than science. It was a piece about Goethe, offered by the flamboyant Darwinist Thomas Henry Huxley in 1869. What happened to a world when it was unremarkable for scientists also to be poets; when a leading English evolutionary biologist was as learned in German philosophy as the new German experiments on a thing called ‘the cell’?

A marriage of literature & science

In writing An Intimate History of Evolution – the story of the Huxley dynasty over four generations – my capacity to read poetry was as tested as my capacity to read the history of biology. All the Huxleys would have thought them equally important. I learned that it was impossible fully to understand their scientific articles, without being able to understand their literary and poetic work too.

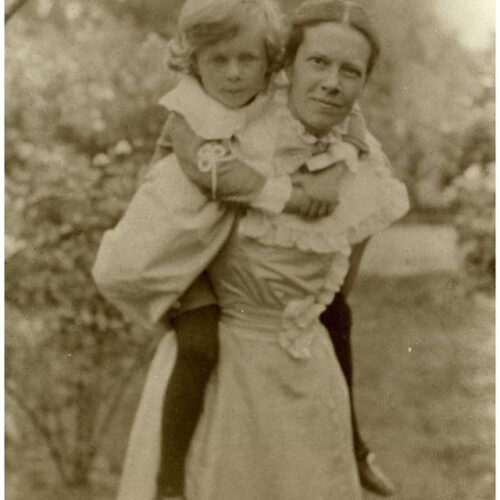

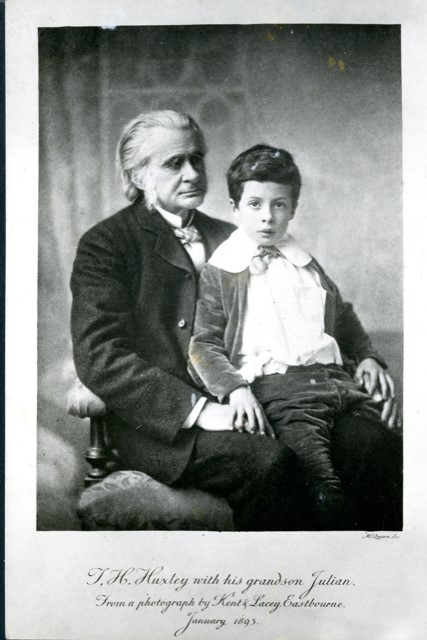

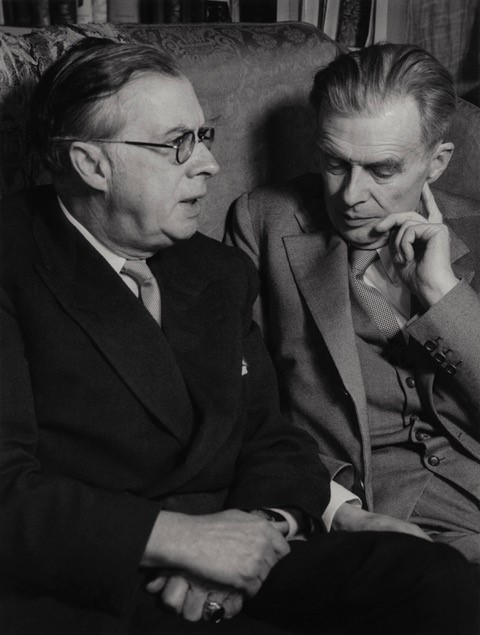

Perhaps this was to be expected. After all, Victorian science and Victorian letters were conjoined when T.H. Huxley’s son Leonard married Julia Arnold of the literary family – Thomas Arnold, Matthew Arnold, Mary Arnold (Mrs Humphry Ward). Leonard and Julia dutifully produced one giant in twentieth-century science (Julian Huxley) and one giant in literature (Aldous Huxley). The brothers certainly read great-uncle Matthew’s phenomenal poetry. But they learned most from the stratospherically successful novelist-aunt, Mary (Arnold) Ward who routinely passed on to her nephews high-level, technical advice on syntax, structure and symbol, as well as uncompromising critique.

A family of poets in public & private

The entire dynasty was made up of professional wordsmiths. They were all published poets, starting with Thomas Henry Huxley himself, as well as his wife Henrietta (on whom he was reliant for a superior translation of Goethe verse). Privately, the family traded in ‘pomes’, poignant iambic pentameter gifts exchanged on special occasions, in moments of grief or joy, or when the depressions from which the family suffered intergenerationally and tragically became too much to bear.

Evolving ideas about generations & genealogy, genes & eugenics

1988, MS512, Woodson Research

Center, Fondren Library, Rice University, Box 16, Folder 3.

Julian Huxley was an accomplished and prize-winning poet, as well as a key exponent of the ‘Evolutionary Synthesis’ that brought Darwinism and Mendelism together in the middle of the twentieth century. Intermittently paralysed with deep depressions, when he was unable to gather his own words coherently to describe anything let alone such pain, he reached for those of others, confessing publicly how his mind and soul were tortured, how he lived Walt Whitman’s ‘terrible words’: “Death under the breast-bones’, Hell under the skull-bones“.

The family’s most famous wordsmith, Aldous, reintroduced to the twentieth century another term, ‘accidie’. Chaucer’s middle-English described the condition that ‘forsloweth and forsluggeth a man’. This was what was passed from Thomas Henry Huxley to his grandson, and what was inherited here and there across the wider Huxley family.

What agonised the Huxleys personally, fascinated them intellectually and scientifically: what do we inherit and what inheres in us? What happens over and between generations of living beings? How is similarity and variation carried forward over time, measured in the generational years of a family tree; in the tens of thousands of years in ‘the tree of man’; or even more expansively in the great geological epochs in the ‘tree of life’? What do we really know about breeding, whether of peas, pigeons, horses, or humans? The family history of the Huxleys doubles as an account of evolving ideas about generations and genealogy, genes and eugenics.

The science (& poetry) of love

Wells, The Science of Life, vol. III (London: Waverley, 1931), 823.

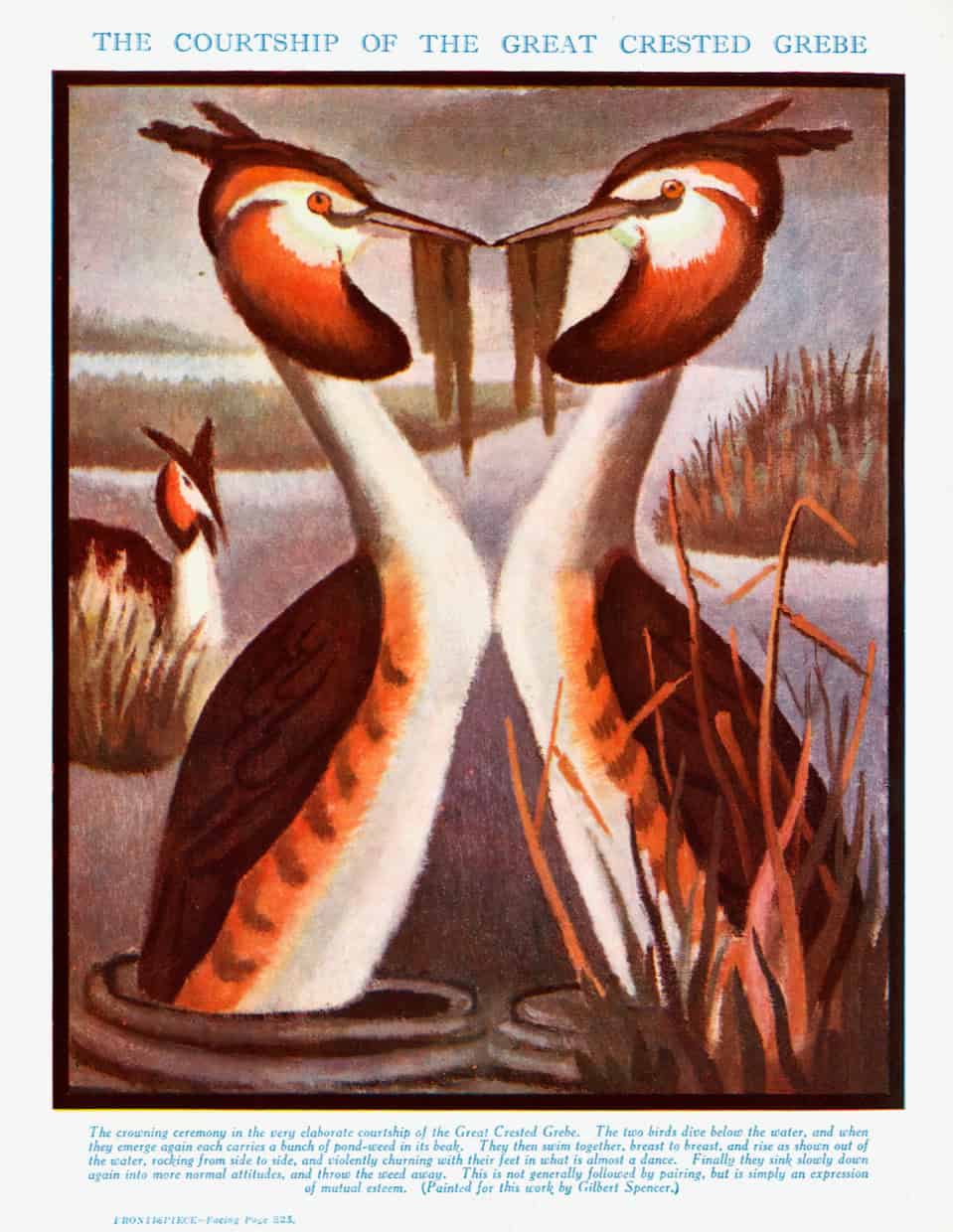

Julian Huxley’s best-known zoological work remains, to this day, The Courtship Habits of the Great Crested Grebe (1914). It is a much-cited classic in ethology, and importantly a challenge to Charles Darwin’s other theory, that of sexual selection. These water birds, unlike Darwin’s peacocks, were minimally sexually dimorphous. It was difficult to distinguish between the female and the male. How then did sexual selection work? An ethologist, Julian Huxley wondered about the behaviour of mate-finding, even the science of love, as he himself put it, in all species.

Few zoologists these days would likely read to the end of his famous article on bird behaviour. In it, we see that there was no keeping this Arnold/Huxley from the literary canon. His article on grebes in the Proceedings of the Zoological Society suggests that we might best look to Dante, or to the lovers in the George Meredith novel The Ordeal of Richard Feverel, or to Romeo and Juliet to think through mate-finding behaviours and (important to Huxley in technical evolutionary terms), the emotions that went with them.

Even more gloriously for what is one of the founding studies of ornithological ethology, Julian Huxley reached back to the classics, quoting from Plato’s epigram to the handsome Athenian poet Agathon, ‘Lovers’ Lips’: “Kissing Agathon, I had my soul upon my lips”. And so, the science of love for Julian Huxley was traceable between species, with equally weighted evidence magnificently drawn from the man-poets of classical Athens and intricate expert observation of the sexually monomorphous water birds of Tring Reservoir.

The history of science is the history of humanities.

About the author

Alison Bashford is Scientia Professor of History at UNSW and Director of the Laureate Centre for History & Population. Her latest book is An Intimate History of Evolution: The Story of the Huxley Family (Allen Lane, 2022).

Alison Bashford is Scientia Professor of History at UNSW and Director of the Laureate Centre for History & Population. Her latest book is An Intimate History of Evolution: The Story of the Huxley Family (Allen Lane, 2022).

Alison will be in conversation with Robyn Williams (The Science Show, Radio National) about the Huxleys and the history of science on 2 March 2023, 6 pm at the State Library of New South Wales. Register now to attend the event.