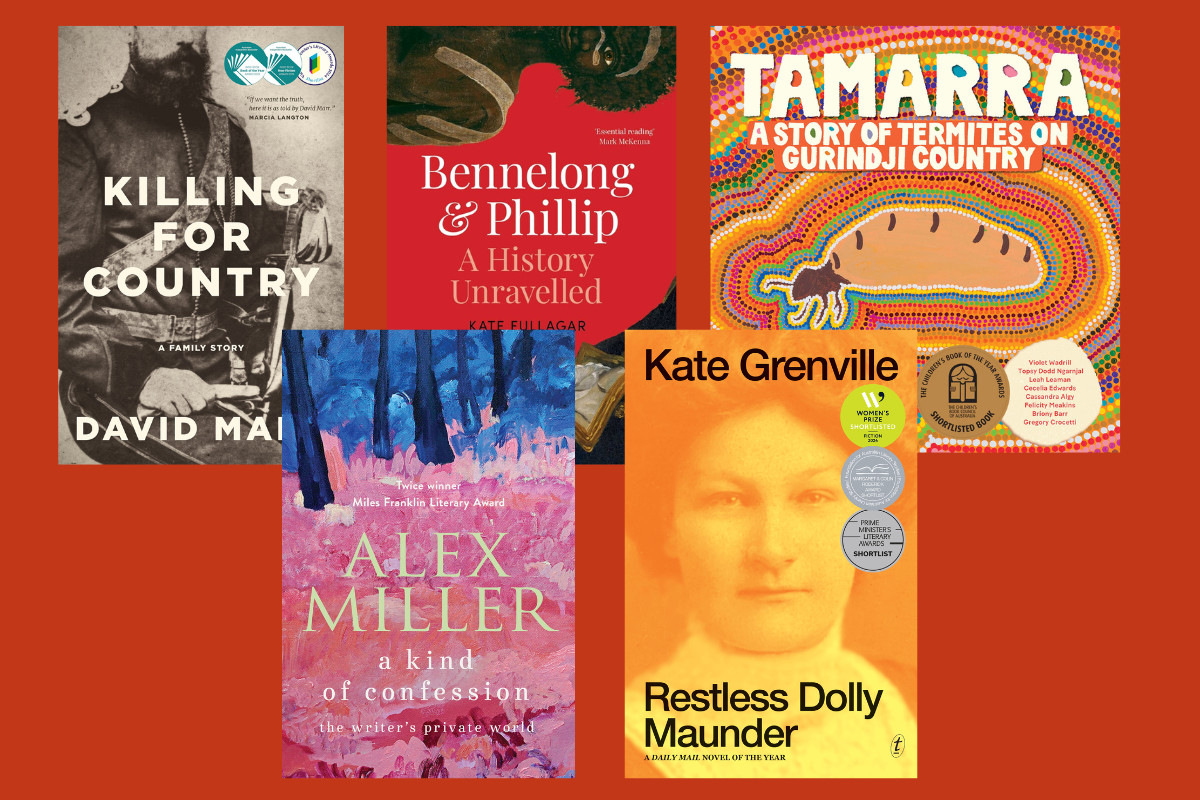

Democratic pluralities & the future of Australia

Professor Kate Fullagar FAHA FRHistS: I thought that we might begin with a discussion of periodisation. You’ve described your era of main focus to be 1780 to 1850, also known as early colonial Australian history. You’ve noted a decline of interest in this area over the past two decades amongst students and the public. What does this era mean to you, and what do you think it means for the nation’s past?

Emeritus Professor Alan Atkinson FAHA : Early colonial Australian history adds depth to our collective memory. It’s an essential extra layer to understanding the Australian past, and I think it’s an enormously valuable asset to Australians, which we tend not to use as much as we could.

Particularly during the Trump years, a lot of American commentary on current affairs drew on American history — I have been really struck by the way American commentary depends on a very deep understanding of their own past. Obviously, that’s not universally shared but they talk about the pre-democratic past as if it matters for their current affairs now. They know the names; they know something of the characters of people in the remote pre-democratic past and so the conversation has a kind of depth that those same topics don’t have here.

Australians might occasionally mention the pre-democratic past, but it’s superficial and it’s not necessarily very well informed. They say we’re descended from convicts without thinking too much of it. Aspects of our history that have prefigured the way we do things now are often overlooked, not considered or not well understood. And that’s pretty disappointing.

Fundamentally, this thinking hinders our understanding of what democracy is. I don’t think you can really understand democracy unless you understand pre-democracy and what the alternatives might have been for Australia.

There was a lot of discussion about democracy in the states before Federation — people tried to understand the advantages and disadvantages. The idea of democracy sometimes significantly changed from colony-to-colony. How these differing stances were reconciled doesn’t really figure anymore in Australian discourse — that sort of sense of variety, diversity and the plurality of possibilities as to what Australia could have been — other ways Australia could have formed—is not part of our discussion today at all.

Kate: I agree with you about the lack of depth in our discourse, and that becomes more apparent when you can see parallel discussions in Canada or the United States. But I think there’s also been a decline from a former higher level. Two generations ago, researching that early period of Australian history was more popular. If you were doing your PhD now, I would guess you’d be the only person in your department studying that time period. What do you think explains the decline?

Alan: I think it’s certainly true — I’m rarely asked to examine theses these days! Partly for that reason, my work is no longer relevant to students as they’re not working in the area. In my generation, the pre-Federation period was still a period where it was almost in the living memory of elderly people, so there is a sense that continuity with the past has been snapped.

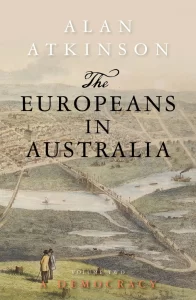

Kate: You’ve published in your career histories of local places, certain people, land, speech, republicanism, and a whole continent in three hefty volumes. Somewhere you talk of the challenge of representing both ‘the mighty plural and the fragile singular’ — which is certainly one way to summarise your body of works together. Let’s talk about the work for which you are best known, the trilogy on Europeans in Australia. In its combined 1,700 pages, you distil indeed the mighty plural and the fragile singular. What made you want to write this work?

Alan: I wanted to tell a story of Australia that made more sense to me than the narratives that were appearing at the time. To begin with, it was going to be a history of New South Wales because that was where I was most involved and it was going to go right back to the beginning of settlement in the 1780s, but then it gradually grew.

The project was a question of telling the story differently — that is, telling the story in a way that made more sense of the individual, the individual conscience and in particular, the pre-democratic individual conscience; a story that took more account of the complexity of moral issues.

I remember a moment on the train looking over the suburbs of Sydney — trains are great places for thinking — I remember that sense of wanting a total view but from another perspective, so that was the ambition.

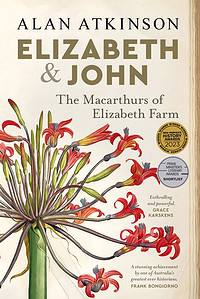

The Macarthurs and being a ‘native of the Enlightenment’

Kate: Your last book was a return to a familiar topic for you, the Macarthur family, published as Elizabeth & John. Many Australians might have felt it was a familiar topic for them too, but you make these characters appear so fresh. For me the most compelling part was how you presented them as ‘natives of the enlightenment’. Enlightenment is word that does not get debated too much by historians in Australia, I think. So, I want to discuss what does being a “native of the Enlightenment” means to you?

Alan: I kept thinking all the time about how being a native of the enlightenment is being comparable to being a digital native — it captures that generational change. There’s a bit of work being done in England lately about the last three decades of the 18th century, a period of revolutions, and about the way children who grew up in that period, as Elizabeth and John both did, were very different from their parents. There was a sense of new horizons, of being educated, of being aquainted with books. They were able to communicate across great distances with enormous speed as the postal system expanded.

Those of us who grew up in the 1950s and 1960s had the same sort of feeling, as do the people who were born in the 1990s. There’s a significant generational gap between parents and children. Young people have a sense of knowledge, power, and access to technology that their parents didn’t have.

I was really interested in the idea that Elizabeth and John were ‘self-consciously modern’ — they knew they were doing things differently — and of course that term ‘self-consciously’ gives a sense of power, of rebellion.

Kate: I’m interested in how people use the term Enlightenment in contemporary discussion. I notice that in the Voice debates last year people from all different sides of the spectrum used the word ‘enlightenment’ to convince voters one way or another. It’s quite clear there’s absolutely no consensus on what the word ‘enlightenment’ means. What do you think of the multiple uses of the term enlightenment, for example, in the Voice debate, and what that tells us about Australia’s understanding of the generation, and time-period, of the Macarthurs?

Alan: When it was first being used during the period itself, the term was regarded as absolutely good and it was a poster word, you know, ‘we are enlightened people’. But, at the end of the 20th century in particular, people began to draw back from that identity. There was a sense that the enlightenment also brought certain evils. I tried to make that clear in the book. The sciences for instance were advanced considerably and made an enormous difference. But the manufacture of weapons was also quickly improved. The idea of enlightenment became morally ambiguous — whether it was a good thing or a bad thing, something to love or something to hate…

The historian’s ongoing dilemma

Kate: about a year after you wrote your two-person biography, I also wrote a two-person biography on Bennelong and Philip. I used the first volume of your trilogy as the background to my work. In your review of Bennelong and Phillip, this sentence struck me as so typically you – in topic and form – discussing the historian’s approach to individuals in culture:

Quite apart from the inevitable push and pull that goes on between the two men during their period of contact, we sense a striking ambivalence in the way each of them stands out from their crowd of friends and associates while at the same time being continuously drawn back in. Such is life, now as then.

This is a very nice reflection on this ongoing historian’s dilemma about how we think about individuals on their own but also as seen through a grid of culture. Is that something that you thought about when you were depicting Elizabeth and John as well? Two individuals constantly being drawn back or being defined by their own group but then trying to find their delineations themselves? Is that something that played in your mind?

Alan: In the first instance, I was interested in the phenomenon of marriage [between Elizabeth and John] and how it relates to the self — going back to what you owe yourself and what you owe other people, and how you balance those two things.

I always found my parents’ marriage fascinating; I remember watching their marriage when I was young and thinking of it as a kind of ongoing theatre.

I mean, they were very different people, but they were fond of each other and that sense of to-ing and fro-ing in their marriage was something that has fascinated me ever since, really.

When that sort of problem is not just between two individuals but between an individual and a massive number of individuals, or a collective working as a single force, that introduces other issues. But it’s the same basic problem.

Kate: Is it a problem that you’re thinking about in your new project?

Alan: My current project is on Penelope Lucas, who is best-known as the Macarthurs’ governess. But she was much more than that — she was a woman with particular talents and she lived with the Macarthurs, using those talents, for the last thirty years of her life. There’s quite a bit of evidence about her family but very little on Penelope herself. She never married; she never had any romantic attachments that I can find, and I’m interested in exploring what her life was like, and how it’s possible to make sense of the silences that surrounded her then, and even more surround her now.

This is a problem, more generally, for female figures in the past — the silence that surrounds them is often almost completely overwhelming.

Kate: Reviewers of yours always mention the style of your writing; they talk about you being ‘one of the finest writers in the country’, with ‘trademark lyricism’, ‘easy elegance’, and so on. Do you think there’s a connection between your evident interest in philosophy and fiction that has made you the kind of writer of history you are today?

Alan: I do read a lot of fiction — particularly 18th and 19th-century fiction; not so much 20th-or 21st-century fiction. I read all of Jane Austen in preparation for writing the first volume [of Europeans in Australia], and Charles Dickens for the second volume. Those writers are commenting on their time, they’re saying things you don’t find in the cut-and-dried accounts. You can translate those sentiments into your own writing in such a way that you could never do if you simply relied on demographical travellers’ accounts.

Kate: Your skill has been reflected in the amount of prizes that you’ve won; I don’t know if you realise this, but you are the Taylor Swift of the Ernest Scott Prize, because she’s the only person to have won four Grammys for Album of the Year, and you’re the only person who has won the Scott Prize four times — which is arguably the most prestigious prize for historians in Australia.

Alan: [Laughs] I must get that information to Taylor Swift! I’m sure she’ll be delighted by the comparison. But those awards do mean a lot to me; it means a lot to me that people enjoy reading the books. It also means a lot to me to be a part of a profession; to be loyal to a profession. We’re very lucky in Australia to have a community of scholars who are extremely generous to each other as a whole.