The relationship between China and Taiwan is often portrayed as being locked in an irreconcilable impasse. This perspective ignores the complexity and vibrancy of cross straits connections. The people in the great mainland of China and the small neighbouring island share common ground, common history, and common concerns as well as differences.

Communication persists despite the geopolitical tensions even while those exchanges may not be immediate or linear, and may happen in unfamiliar forms and in unexpected places.

Artists and their artworks have been instrumental in creating new modes of communication that transcend time and space — as Meng-Yu Yan’s 颜梦钰, exhibition Double Witness showing at the ANU’s Australian Centre on China in the World reveals.

Tracing the footsteps of those who come before

Double Witness showcases the power of art to communicate across multiple borders and to build surprising bonds among audiences and artists. Yan, a gifted photographer and finalist in the 2023 National Photographic Portrait Prize, is a queer, non-binary, first-generation Chinese-Australian artist with extended family still in mainland China. Their exhibit consists of a series of video letters created during a 2019 artist’s residency in Paris.

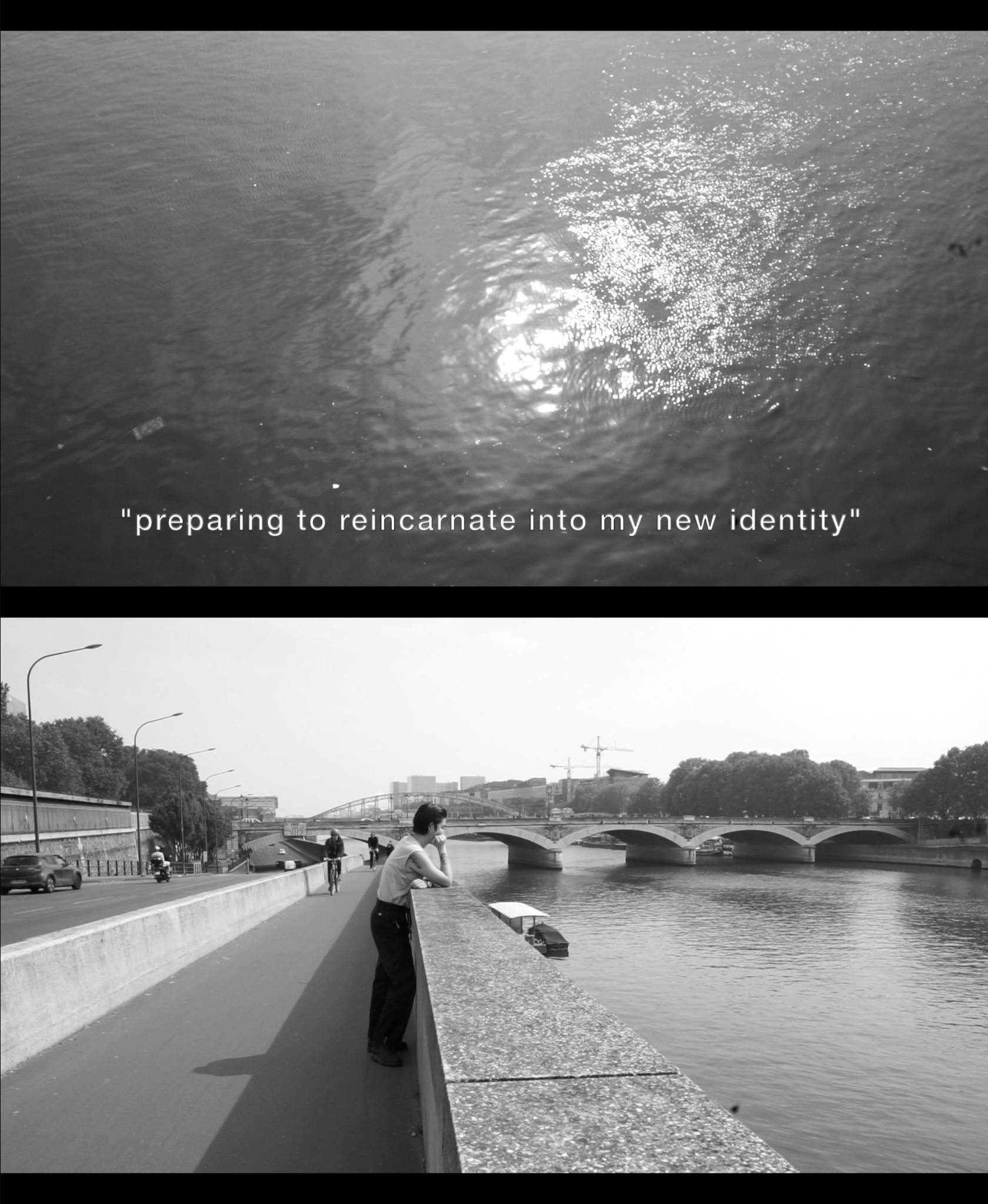

Yan’s videos trace the final footsteps of the late Taiwanese lesbian author Qiu Miaojin 邱妙津, who took her own life in Paris in 1995. Qiu left behind the experimental memoir, Last Words from Montmartre, that details life during her final three months – descriptions of meals, and locations of various key events, right down to precise dates.

Decades later Qiu’s 1995 memoir became inspiration for Yan’s art. A transnational conversation that transcends time, space and generations, is built.

Parallel lives, decades apart

Yan’s engagement with Qiu’s book is a powerful exhibition of black and white images punctuated only once with a shaft of colour to mark Qiu’s birthday. The videos present a quiet, internal journey as Yan’s own life begins to mirror Qiu’s in uncanny ways.

At the time of their trip to Paris, Yan was the same age as Qiu.

The artist’s long-term relationship with an Australian partner ended, and a new one with a French partner began, in circumstances precisely mirroring those recorded by Qiu.

Yan’s menstrual cycle even occurred on the same dates as Qiu’s.

A glass case at the back of the gallery displays evidence of this inter-generational and inter-continental communication, including copies of Qiu’s book in Chinese, complete with translator’s notes in the margins; the English translation, complete with notes by the artist; love letters; ID photos; and even a rare copy of the mainland edition of Qiu’s novel.

We are the witnesses

The ‘double witness’ of the exhibit’s title can refer not only to the artist’s experience of witnessing the life of the late Taiwanese author, but also to our experience, as viewers, as we participate in the act of witnessing in the gallery.

When viewing Yan’s work, it’s important to remember the circumstances of its production.

Qiu was writing in Taiwan and Paris in the 1990s. Her work circulated among lesbian communities not only in Taiwan and Hong Kong but also in bootleg copies passed hand-to-hand in mainland China too.

Qiu was ‘known’ in China long before her work was ever officially published there. But Last Words wasn’t translated into English until 2014, and Yan only encountered the book when an ex-girlfriend alerted them to a review by a favourite writer, the American poet and novelist Eileen Myles. Yan then began to think about travelling to Paris to trace the author’s footsteps.

> Visit Double Witness at the ANU in Canberra until 16 June 2023

From author to artist to gallery visitor

Now, in Canberra we’ve had visitors to the gallery from all over the Chinese diaspora, many of whom are in their 20s and have much in common with both artist and author in terms of gender, sexuality, national origin, family ties, and experience of navigating the challenges of living abroad.

Historically, queer communities have had to find new ways of communicating across the barbed wire fence of everyday language, political culture, and media, so perhaps it’s unsurprising that we find this kind of trans-generational, trans-cultural and transcontinental communication here – people persist in finding ways to communicate, even when mainstream media might suggest otherwise.

That’s why in the gallery, a letter from Qiu to her readers becomes a letter from Qiu to the artist Meng-Yu Yan. And a video letter from Meng-Yu Yan becomes a letter to us.

Across time, space, and even life and death.