In 2017, researchers discovered ceramics, dating between 1,800 and 3,000 years old, in an archaeological excavation on Jiigurru conducted by the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage (CABAH) in partnership with the Dingaal and Ngurrumungu communities.

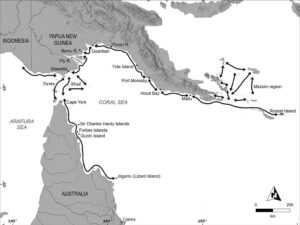

The pottery sherds indicate ancestors of the Dingaal and Ngurrumungu communities traded goods, culture, and knowledge across the Coral Sea, and both used and created pottery in Australia.

Additionally, the remains of fish and shellfish discovered within the midden indicate the island was regularly occupied over 6,000 years ago, making Jiigurru the earliest known offshore islands occupied in the northern Great Barrier Reef.

Dingaal man Kenneth McLean grew up with the story of the totem, Jiigurru (stingray), and how his ancestors would travel in canoes to the island of Jiigurru for ceremony, dance, and songline, and trade with people in other communities across Australia and the Coral Sea.

‘For the Dingaal people, Jiigurru is a sacred place for connecting to Country,’ says Kenneth. ‘We always knew Jiigurru was there. Our law was always there, our story was always there, our songline was always there.’

‘In collaboration with archaeologists now, you could piece that all together. Our people would trade with the neighbouring clans that would stretch up the east coast of Australia. That went on for thousands and thousands of years, which is a good thing for my people to understand and learn from.’

Sharing the ambitions of Traditional Owners

The research team comprising of 40 researchers from 26 institutions was led by CABAH Chief Investigators Distinguished Professor Sean Ulm FAHA, (James Cook University) and Professor Ian McNiven FAHA (Monash University). All research is undertaken in partnership with the Dingaal and Ngurrumungu communities, represented by Kenneth McLean and Ngurrumungu Elder, Brian Copus.

‘Historically, Indigenous communities have been marginalised in the research process,’ says Sean. ‘If we consider the founding figures of archaeology, work in the 1960s and 70s rarely involved Aboriginal people, often even when the research was about them. While things gradually changed over time, with archaeologists developing projects to take to a community seeking approval, we are now prioritising co-design in everything we do.’

‘The co-design process brings different skills, knowledges, and experiences together which in turn leads to fulfilling the aspirations of communities. Personally, this is the most gratifying type of research I’ve ever done.’

Sean and the team at CABAH visited the Dingaal and Ngurrumungu communities in northern Queensland many times over the past decade, speaking to Elders and the community to understand what their aspirations were and how they could work together to achieve them.

‘One of the big priorities for the Traditional Owners was mapping their cultural heritage on their traditional lands and seascapes, and to make sure these were documented so they could be protected into the future.’

Working together on Country

The project marked the first time the Dingaal people had worked with archaeologists.

‘We work together on Country, sharing each other’s story on Country,’ says Kenneth. ‘And not only sharing this story from our people, the Old People, and from the archaeology side, scientifically, which is a good outcome that we can see. We can look after Country together.’

Jiigurru, and the wider Great Barrier Reef, is heavily impacted by tourism, climate change, and natural disasters like cyclones.

‘For the last 20 or so, 30 years, 50 years, a lot of stuff got destroyed on Country,’ says Kenneth. ‘Having these stone arrangements destroyed, cave paintings destroyed, that’s a lot for us. Jiigurru is a part of the history of the Dingaal people.’

‘The more of this type of research that is done, the more communities will be empowered to direct their own research,’ says Sean. ‘And this will not only lead to better research outcomes, but also honour the integrity of Indigenous knowledges and sciences which have otherwise been historically marginalised.’

Mentoring the next generation of humanities researchers

Dr Ariana Lambrides was one of dozens of early-career researchers working on Jiigurru, having joined CABAH in 2018 as a post-doctoral researcher.

‘Not everyone gets the chance to work on Country in these large-scale research projects,’ she says. ‘I had the opportunity to be mentored by Sean and Ian, two senior and highly respected academics, but I was also mentored by Elders and Traditional Owners as well. Experiencing the co-design process first-hand and seeing the outcomes it produced for the community was life-changing.’

Why are we doing what we’re doing if it’s not coming from genuine community aspirations to do that work?

Ariana continued to work on the Great Barrier Reef, building on relationships she’d formed with Traditional Owners.

‘A few years later, I started another research project studying how First Nations actions transformed marine systems and modified fish communities pre-European settlement, in partnership with a number of Queensland coastal communities. That project received a Discovery Early Career Research Award (DECRA) from the Australian Research Council in 2021.’

The impact of working on this project continues to shape Ariana’s career.

‘Soon after receiving the DECRA, a continuing position at James Cook University in Cairns opened, so I applied. Now I have a continuing lectureship and research position where I can teach this work to future generations and continue working on research with communities on the Great Barrier Reef. I wouldn’t have been competitive for that position without the mentoring and support I received through CABAH.’

Want to learn more? The story of Jiigurru is featured in The First Inventors, episode 3, directed by Larissa Behrendt FAHA, featuring Sean, Kenneth and Ariana. Watch on SBS On Demand.