I think therefore I am

It’s a question that has tantalised philosophers since Plato and Aristotle: what, exactly, is the human mind, and how does it relate to the brain or body?

The seventeenth-century French philosopher René Descartes claimed to have solved the puzzle. He was convinced that the mind and body were separate and distinct, with the soul-like mind transcending the physical brain. The mind, with its memories, emotions and beliefs, was spiritual, ethereal, something different.

This “dualism”, or varieties of it, is still espoused by some philosophers. However, since the mid-twentieth century it has been fundamentally challenged. One of the most influential rival theories was “Australian materialism”, most powerfully articulated by the late David Armstrong in his 1968 book A Materialist Theory of the Mind.

Armstrong’s work, and that of other champions of materialism, revolutionised the way that philosophers internationally have since viewed the mind and sought to explain human consciousness. While their ideas were not universally accepted, they changed the course of philosophical discussion about the mind and continue to have a major impact today.

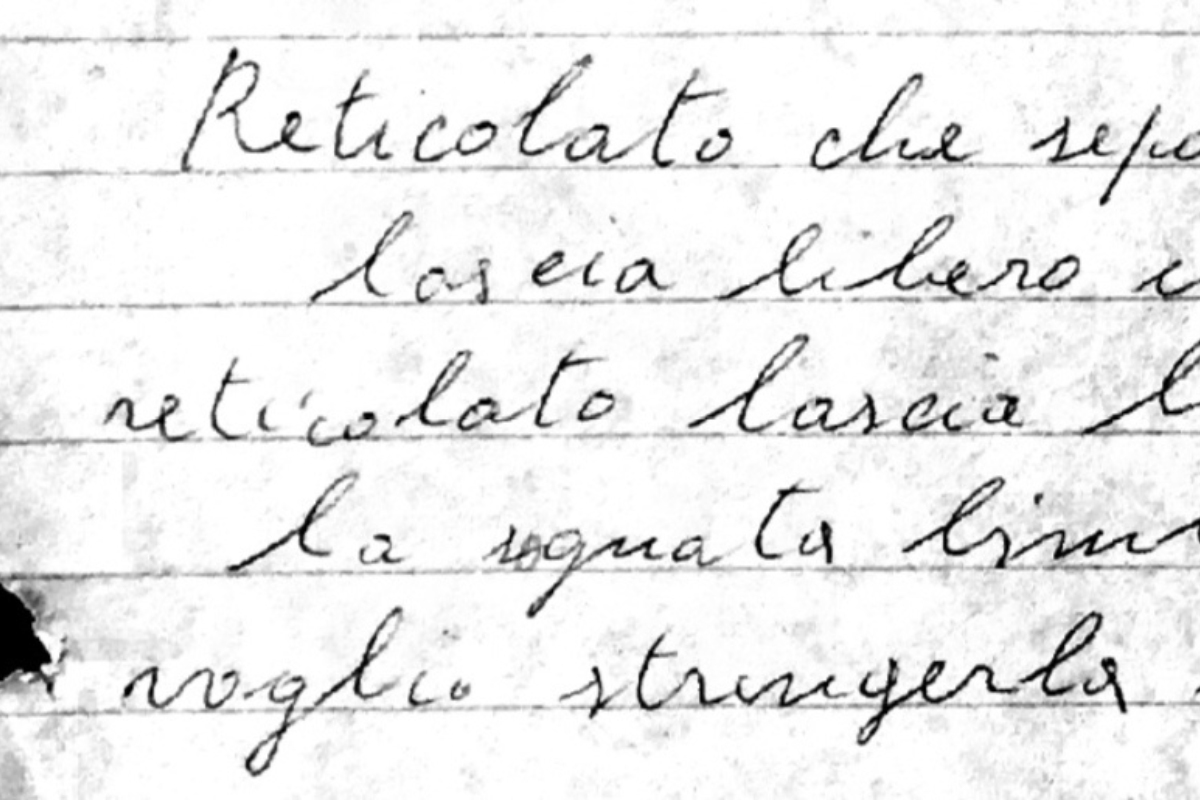

Did this brain contain the consciousness of UT Place?

Armstrong, regarded as one of Australia’s foremost twentieth-century philosophers, believed the mind and brain are not just inter-related, but one and the same. The mind, Armstrong argued, is not intangible and mysterious. It’s material, it’s physical matter, and every type of mental state or process – such as anger or a visual experience – corresponds to a type of brain state or process.

He was inspired by two other outstanding philosophers, English-born U T (Ullin) Place and Scottish-born J J C (Jack) Smart, who were at the University of Adelaide together during the 1950s.

Place’s landmark paper, “Is Consciousness a Brain Process?”, published in 1956, challenged both dualism and another prevailing theory, behaviourism. He contended that all conscious processes – thoughts, feelings, desires, a sense of self – equate to neuro-physical processes, questioning:

“the view that there exists a separate class of events, mental events, that cannot be described in terms of the concepts employed by the physical sciences”.

On his death, Place bequeathed his brain to the University of Adelaide, to be displayed with the words: “Did this brain contain the consciousness of UT Place?”

Smart also wrote a celebrated paper, “Sensations and Brain Processes”, published in 1959, which asserted that conscious experiences would eventually be explained by neuroscience. “I wanted a metaphysics which was plausible in the light of total science,” he observed later.

A materialist theory of mind

It was Armstrong who enunciated and developed these arguments most compellingly, in A Materialist Theory of the Mind, which received international acclaim. He expanded Smart’s and Place’s theory into a more comprehensive and ambitious form, which he called Central State Materialism.

The nature of mind and consciousness is still hotly debated today, and is all the more fascinating in light of the possibilities opened up by Artificial Intelligence.

Other theories have gained currency, especially functionalism, which considers mental states and processes to be tied to their functional roles. But as neurologists search for a scientific explanation for consciousness, materialism remains a core idea in philosophy of the mind.