A tale of two cities

The discovery of ancient cities and monuments enriches our knowledge of human civilisation. What really captures our imagination, though, is learning about the everyday lives of those who inhabited them, their relations with their own world, and interactions between colonisers and colonised peoples.

Two major projects by Australian archaeologists have delivered such insights: about the Hellenistic city of Jebel Khalid, in modern-day northern Syria, and, in Ancient Egypt, about the region of the Beni Hassan tombs.

Jebel Khalid was a walled fortress town on a high limestone plateau overlooking the Euphrates river. It was founded as a military colony in the early third century BCE, under the Seleucid Empire established by one of Alexander the Great’s generals. In 1984, the ANU’s Graeme Clarke came across some pottery fragments and the remnants of a city wall.

For the next quarter-century, a team led by Clarke and others, including Heather Jackson, excavated and studied the site, with its Manhattan-style street grid, walled acropolis, governor’s palace, temple, gymnasium, commercial area and houses.

Daily life from above & below

Unlike many ancient cities, Jebel Khalid had remained unoccupied after being abandoned around 70 BCE, meaning it had preserved its original character.

Jugs for oil and wine, bowls and cooking pots, figurines, lamps, coins and animal remains have yielded, as one review of the team’s work noted,

“a full, clear and interesting view of real life – both upstairs, in the governor’s palace, and downstairs, in the domestic quarter”

According to the researchers, people were “drinking out of elegant cups and eating off … small saucers, fishplates or large platters.”

Jebel Khalid’s layout, building design and modes of worship reveal significant local input, indicating that the colonisers adapted to Near Eastern culture and tastes. The temple was a hybrid of Greek and Mesopotamian architecture. Aramaic lettering was found on ceramic jug handles. Clearly, the newcomers mixed with local merchants, craftsmen and farmers.

The excavations have been halted by the Syrian war, and the fate of artefacts stored in Aleppo’s museum is unknown. Sadly, Graeme Clarke died in 2023.

The cliffs above the Nile

At Beni Hassan, meanwhile, it is feared that human handling could threaten the Middle Kingdom tombs, carved into cliffs above the Nile’s eastern bank and containing remarkable wall art.

Although excavations have been carried out at the site since the mid-nineteenth century, a Macquarie University team led by Naguib Kanawati is unearthing new information about ancient Egyptian life, and shedding fresh light on a hotly debated question in Egyptology: the purpose of tomb paintings.

The team, which has been excavating at Beni Hassan since 2010, is also making its treasures accessible to a wider audience. In partnership with New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, researchers have published a series of books on the tomb’s paintings, architectural features and biographical inscriptions. They are also developing a digital archive of high-resolution photographs, line drawings and architectural plans.

Scenes from the tomb

The unusually intact paintings contain colourful scenes of daily life for regional rulers. Kanawati’s team has deciphered images seldom encountered in Egyptian art, such as very early depictions of cats, hunting scenes, and the first record of a fishing technique still practised by Egyptians today.

One provincial governor, Khnumhotep II, is seen spearing fish in marshlands from a papyrus boat, catching waterfowl, and hunting wild animals including oryx and hartebeests (two antelope species) in the desert, accompanied by a dog wearing a rope collar.

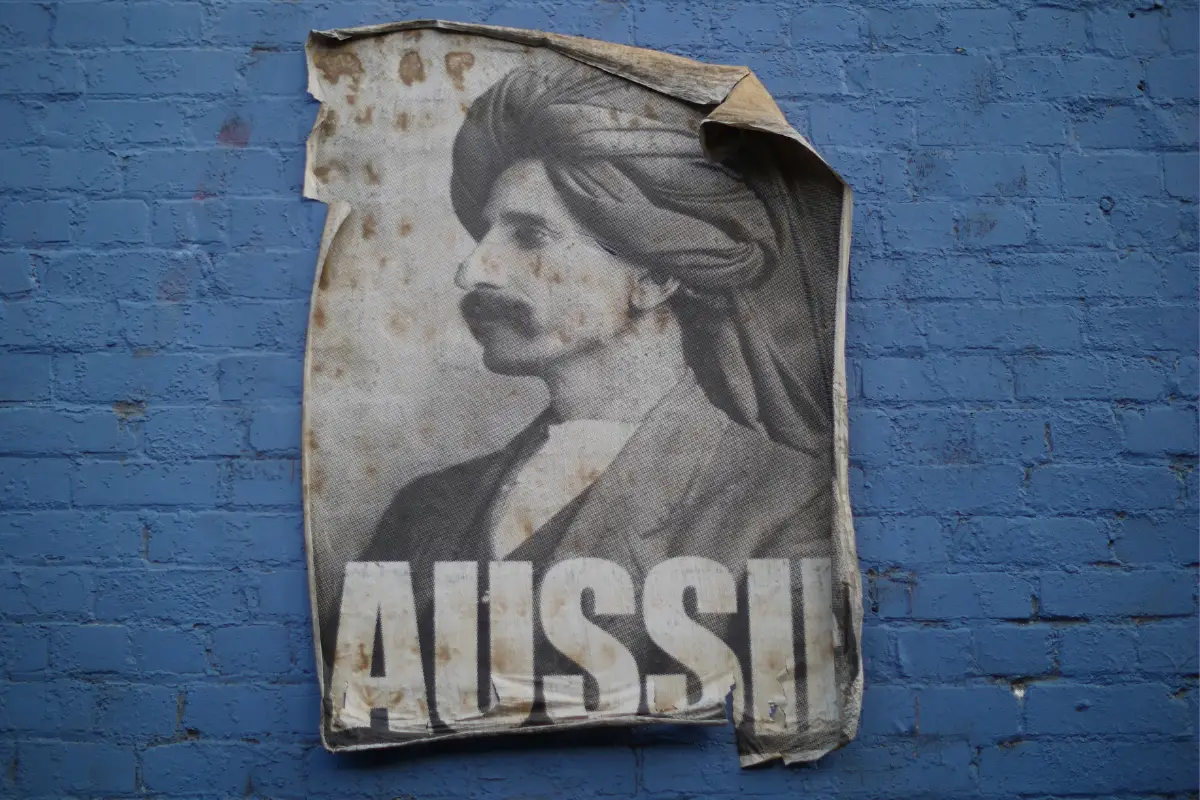

In the tomb of Khnumhotep II a procession of Asians in striped robes is depicted offering up a gazelle. Scenes in the tomb of Baqet III show spinning and weaving, goldsmiths and sculptors at work, and an Ancient Egyptian board game, senet.

Although Jebel Khalid housed a vibrant living community while Beni Hassan houses a community’s dead, both sites tell us much about life in their respective times.