‘Museums’, galleries and collections have existed since the Classical world, but they took on a new cast following the Revolutionary period of the late 18th century. Former Royal collections were made public at the Louvre, and private collectors and public authorities embarked upon coordinated programs of uplift and education for the broader population. Museums held and displayed all manner of things, from ephemera to what was considered high art at the time. A part of the impetus was to improve public taste and also manufactures, as at the Victoria & Albert Museum. A very wide range of world cultures and art forms were on display.

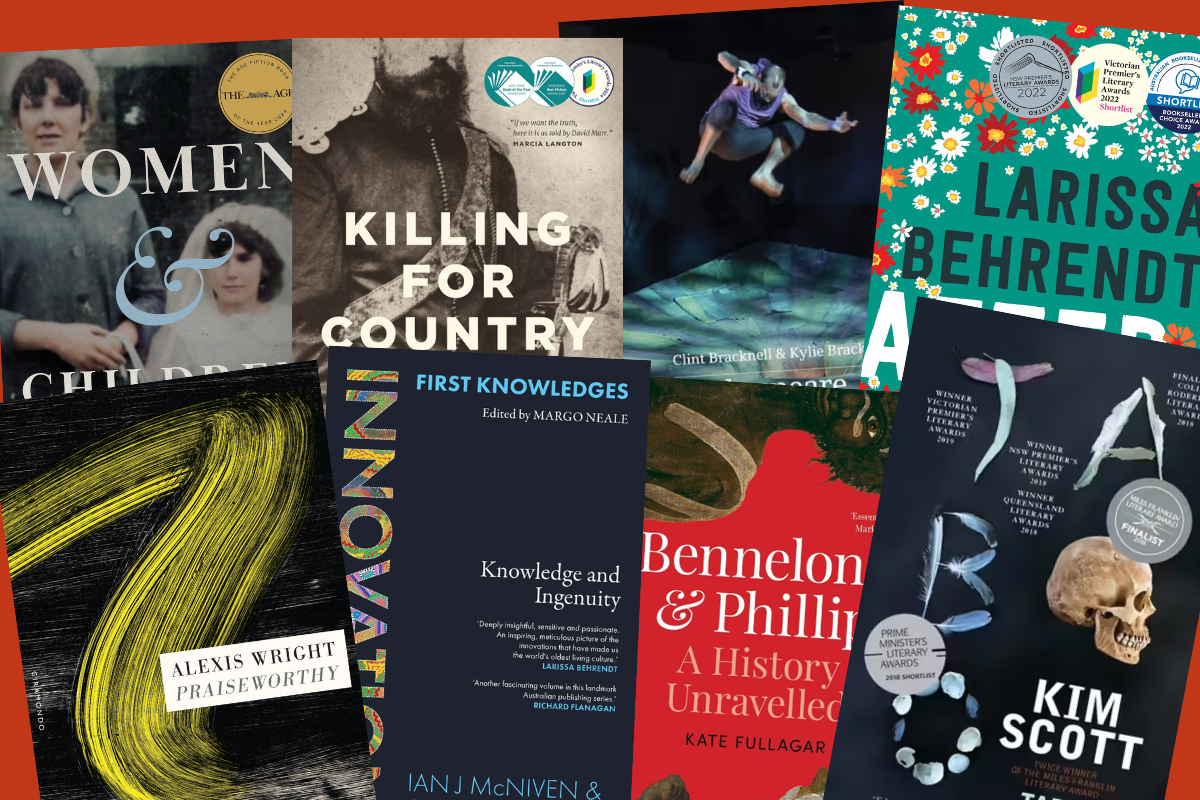

Fashion came late to the museums. At first it was mainly textiles that were collected; they were prized for their technical and artistic accomplishment throughout the 19th century. Collections of dress fashions generally began to move into French museums in the late 19th century, although Royal Armouries and Archives such as Stockholm and Denmark had always treasured the garments of the high aristocracy. The preservation and display of clothes worn by the elites far outnumber items worn by ordinary people. This curatorial trend in part emerged because they were made of splendid or intricate materials that delighted viewers, inspired artists, and boosted new manufacturers. But it was also a result of the fragile position of fashion within museums and galleries more generally. The technical quality and artistic beauty of elite clothing — generally women’s clothing — justified their inclusion in ways that the clothing of ordinary people could not.

Anxiety about the validity of collecting and displaying clothing has sometimes meant justifying it in terms of artforms with a firmer footing in the gallery space, such as sculpture or paintings. The fact that clothing was subject to something deemed as ‘superficial’ as ‘fashion’ required explanation. For example, in 1963, the Museum of Fine Arts Boston exhibited a selection of its dress collections entitled ‘She Walks in Splendour: Great Costumes 1550-1950’ and included a rather apologetic preface in the exhibit’s catalogue by Perry Townshend Rathbone:

There is some constant quality, some inherent merit in the designer’s handling of line, shape and colour that transcends superficial considerations of fashion and lends the favoured raiment the aesthetic validity of a good painting or sculpture’.[1]

In the introduction, Adolph S. Cavallo, Curator of Textiles, discussed the suspicions with which ‘costume’ was viewed in Art History of his day. Dress collecting continues to have a precarious and less prestigious position in the sector. The AGNSW has not held a major fashion exhibition since Yves Saint Laurent Retrospective in 1987.

And, in 1984, the Director of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, Philippe de Montebello, declared that a dress could not possibly be as significant as good piece of Sèvres porcelain, despite the Met’s lengthy history in collecting clothing.

How then did that same museum come to be hosting a fashion event each year that draws designers, models, celebrities, politicians, and journalists together in a media and fundraising extravaganza? Where did the prestige and hype of the Met Gala come from and what does it tell us about the culture of collecting and the role of museums and galleries in informing the public?

Collecting ‘costumes’ in The Met

The Metropolitan Museum of Art currently consists of 17 curatorial departments, ranging from ‘European sculpture and decorative arts’ to ‘Oceanic Art’. The section dedicated to collecting dress was established in 1948 and built from a slightly older Museum of Costume Art that focussed on theatre costumes—becoming a distinct department in 1959. The department undertook curatorial work that in today’s terms was traditional and respectable. That was until 1972 when the appointment of a new Special Consultant would entirely change the shape of the Met’s collection and the way it engaged the public.

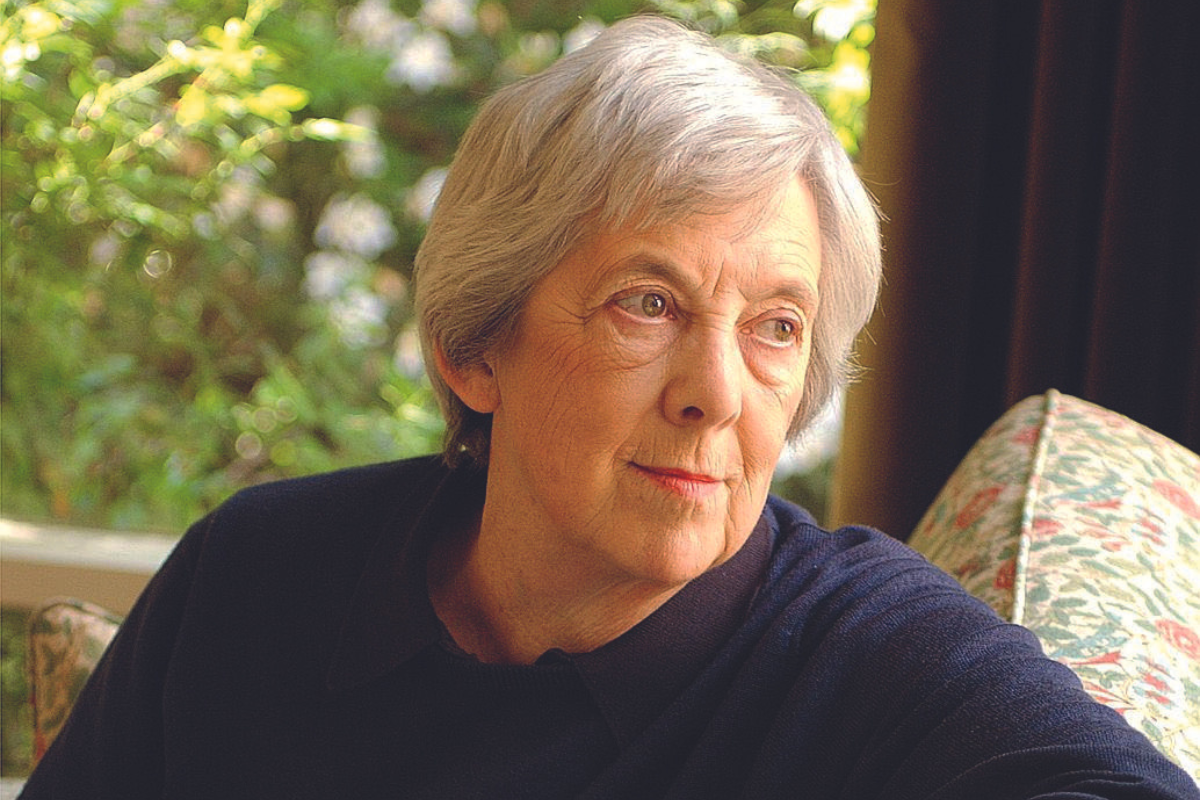

Under its new consultant, the Costume department leveraged the fundraising potential of the huge popularity of fashion exhibitions—only exhibitions about Ancient Egypt are more popular. Her actions caused more than a ripple among conservative museum administrators and have fundamentally changed the position of dress in the museum—with myriad flow-on consequences.

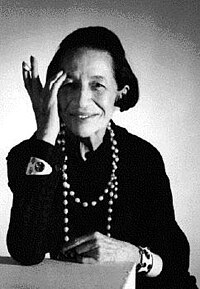

That now-iconic consultant was Diana Vreeland (1903-1989).

Who was Diana Vreeland?

Vreeland was a Francophile Paris-born American who led Anglo-American fashion culture towards a ‘continental’ taste in the post-war years. She joined Harper’s Bazaar in 1936 and, because of her talent and striking personal style, became fashion editor from 1939.

She moved to American Vogue in 1962, and pioneered a fresh layout for the magazine in which text and image were arranged in a dynamic manner—high quality colour photographs were displayed in different sizes, sometimes not much bigger than a large postage stamp, and other times double-bled for maximum impact. In her focus on the rich and famous, Vreeland helped set the format for the reporting of celebrity culture that dominates our media today. For the first time, these magazines allowed ordinary people to witness the lives and vagaries of not just the plutocrat, but also the stylish bohemian, and often in great detail.

On moving to the Met in 1972, Vreeland brought her ‘word picture’ concept to the museum space, creating blockbuster exhibitions such as ‘The Eighteenth Century Woman’ (1982) and ‘Man and the Horse’ (1984) on equestrian clothing. These exhibitions looked more like stage sets than traditional museum displays.

She expanded the museums connections to the rich and famous by encouraging donations of clothing from women such as the Duchess of Windsor.

More horrifying for museum purists was her willingness to have copies of pieces she sought, but couldn’t locate, ‘run up’ for inclusion in exhibitions. Vreeland could never be called an intellectual. But she was urbane, well-travelled, and poetic and revolutionised the funding for the Costume Institute and its cultural and political impact.

Bringing celebrities to the Museum

Despite the rise of counter-cultural movements in the 1960s and 1970s, many of the mondaine international jet-set clung to an old-fashioned pleasure in conventional luxuries and revelled in an Edwardian notion of sensuality. These beautiful people loved going to the glamourous, theatrical Studio 54 nightclub in their fine Yves Saint Laurent evening dresses.

The so-called Met Gala began in 1948 as a fundraiser for the Costume Institute, initiated by Eleanor Lambert, a New York executive who invented modern public relations and the ‘Best Dressed List’. The event was often held away from the Met and called ‘The Party of the Year’ or ‘a Benefit’ party.

Vreeland moved the event to the Met in the early 1970s, revamping the ‘Costume Institute Benefit’ into a glamorous gala that meant it soon became the ultimate, must-have ticket for this set. She attracted celebrities to mingle with political and social elites to an annual event that positioned the museum as a broker of a powerful combination of beauty, wealth and fashion. The likes of Jackie Kennedy, Cher, Andy Warhol would mingle with models and fashion designers and the gratin of international elite. The quiet space of the public museum had given way to a festival of fashion in which the rich and famous clamoured to participate.

This exponential success of the Met Gala is evident today with a single ticket in 2024 costing $75,000—a long way from the $85 of 1973. In 2019, the event raised more than $200 million (USD) for the Institute.

In the 1980s, the general public could buy a reasonably priced ticket and come in for dancing after the dinner was served. The so called ‘Met Gala’ was revolutionised by a new Vogue editor, Anna Wintour, who took over as Chair in 1995. Social media influencers rather than society ladies are now more likely to be on the guest list.

Accompanying the Institute’s Director, Anna Wintour, as co-chairs in 2024, were singer Jennifer Lopez, actors Zendaya and Chris Hemsworth, and rapper Bad Bunny. The event was sponsored by social media giant TikTok and fashion brand Loewe.

As a student, I read an astonishing critique of Vreeland’s approach to museums. Decorative arts scholar Debora Silverman published a clever and cutting book Selling Culture in 1986 that provided an elaborate account of how museum directors have sold out to commerce, sponsors and a new type of vulgar media frenzy. She argued that figures such as Nancy and Ronald Reagan, and their best friends the Bloomingdales, used museums to identify themselves with ancien-régime cultural splendour at the expense of traditional democratic American virtues and values. Silverman argued that the Met Gala and other commercial tie-ins facilitate a merger of economic, cultural and political power within the elites.

Re-reading Silverman, that horse has truly bolted.

All museum workers strive to make genuine meaning of the artefacts they display, and no museum can survive without sponsorship.

Yet, much of what we are shown is uncritical; some is even packaged up by fashion houses themselves, who now for the first time in history have reacquired their own archives at auction and can therefore control much of the narrative — processes, origins, sources and ethics can be obscured.

Museums need to help the visiting public unpack the exhibits they are viewing, assist them in ‘reading behind the scenes’ to affirm their role as trusted archivists of social and historical trends. When people attend a museum, have they learned something? As Valerie Steele reminds us, a museum ‘is not a clothes bag’. Nor is it a department store.

The current Australian governmental obsession with measuring the success of museums to ‘access’ (raw numbers or breadth of access) or the capacity to attract co-badged sponsorship, celebrity participation, and social media tie-ins would astonish even Vreeland.

[1] She Walks in Splendour: Great Costumes 1550-1950. An Exhibition of Costumes, Costume Accessories and Illustration from the Museum’s Permanent Collection (3 October-1 December 1963), Museum of Fine Arts, Boston