In May, I began an experiment. For the past three months, I have been trying to teach the AI application ChatGPT some basic facts about Australian media history. Unfortunately, it has proven to be a very poor student.

My experiment confirmed a widely reported problem – ChatGPT ‘hallucinates’ wrong answers but expresses them with such certainty that they sound very convincing.

My chat with ChatGPT

Here is my July ‘conversation’ with ChatGPT with my annotations in italics.

I ask: ‘Who founded the company called News Limited or News Corporation in the 1920s in Australia?’

ChatGPT says: ‘News Limited, now known as News Corp, was founded in the 1920s by Keith Murdoch, an Australian journalist and newspaper publisher’. (Wrong. News Limited was founded by another brilliant editor, James Edward Davidson, and Gerald Mussen, a consultant for Collins House, the huge industrial complex that developed from mining at Broken Hill).

ChatGPT goes on to explain that: ‘Keith Murdoch was born on August 12, 1885, in Victoria, Australia’. ‘He started his career as a journalist …’ (True).

‘In 1923, Keith Murdoch purchased the Adelaide-based newspaper called The News’. (Wrong. Murdoch bought the company News Limited (which owned The News) in 1949. He was chairman of the board of the Herald and Weekly Times and persuaded – some said ‘conned’ – his board colleagues into selling him the majority stake in News Limited. The Herald and Weekly Times had owned a stake in News Limited since 1929).

ChatGPT continues… ‘Under [Keith Murdoch’s] leadership, The News experienced significant growth and success’. (Wrong. It stagnated under Keith. His son, Rupert, drove its growth later).

‘Building on the success of The News, Keith Murdoch expanded his media holdings. In 1927, he acquired The Courier in Brisbane and The Herald in Melbourne’. (Wrong. Keith Murdoch acquired The Courier in a personal capacity around 1933 and quickly merged it so it became the Courier-Mail. He never ‘acquired’ the Herald. His son did in 1987).

ChatGPT concludes… ‘In 1929, Keith Murdoch merged his media assets, including The News, The Courier, and The Herald, to form a single entity known as News Limited … the founding of News Limited in the 1920s by Keith Murdoch marked the initial establishment of the media conglomerate that would evolve into News Corp’. (By this point I had lost patience as none of this is true).

ChatGPT provides a box where you can indicate if you are happy with its answer. I clicked on the thumbs down icon, ticked ‘This isn’t true’ and provided the correct information. I asked my question again and ChatGPT regurgitated my correct answer. I was happy … but only briefly. When I repeated the exercise a day later, ChatGPT had reverted to its original answer, and months later, still incorrectly insists that Keith Murdoch founded News Limited.

Why AI gets it wrong

ChatGPT provides a warning that ‘ChatGPT may produce inaccurate information about people, places, or facts’. It is not kidding.

Generative AI systems like ChatGPT and Google Bard are trained on human-generated datasets. They are fed huge amounts of data which they use to produce outputs, but have to teach themselves rules about how to understand all of that data. It is often unclear how they make those decisions; even to their programmers.

Historian Johannes Preiser-Kapeller points out that, ‘because [AI] models ultimately don’t understand what they’re reading, they can arrive at absurd conclusions’.

Currently, large language models like ChatGPT are just blending and regurgitating information from the internet, acting like a distorted mirror that reflects the often sorry state of online content but also fabricating information to fill gaps.

According to tech experts, generative AI applications will continue to make up information for years to come and won’t learn well until they are in widespread use on mobile phones.

The future of AI

There are plenty of dire forecasts about AI. A recent headline in the New York Times was ‘AI Poses “Risk of Extinction,” Industry Leaders Warn’.

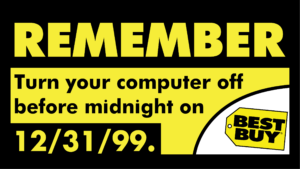

New technology has often caused concern. The introduction of radio had some people worried that it might cause strokes, sterility, thunderstorms and drought. Others believed it could be used to communicate with the dead, or cure cancer. In 1999, the Y2K scare saw widespread concern that computers unable to handle the date change to 2000 would cause extensive havoc.

It’s too early to tell how dangerous AI will be. Right now, it publishes false information. It uncritically reflects bias, prejudice and discrimination. It has no respect for copyright, privacy or security, and no ethical framework. And it will certainly displace jobs.

But AI also has potential; for example, to end car crashes and diagnose health problems, detect fires and predict food shortages, and translate brain activity into words for people who have lost their ability to speak.

During this transition period, what can researchers do to teach AI?

Making AI more human – and more accurate

Humanities researchers are at the forefront of providing advice to governments about creating better and more trustworthy foundations for AI.

Many have already relied on AI-powered search engines, maps and databases, including the National Library’s TROVE archive, which uses machine learning and AI to enhance discovery of its digital collections.

Other researchers use AI to recognise Shakespeare’s writing style, to decipher handwriting in archival documents, translate lost languages, classify illustrations from texts, and trace names that appear across historical documents to reconstruct social networks.

But, researchers also need to populate the internet with information so that AI gets its facts straight and tells the truth. Google recently added to the urgency of this task when it announced that its search engine will soon display an AI-generated answer as the first answer. Many people will rely on that top answer and look no further.

Things we can do right now

Google’s model will rely on free information rather than sites behind a paywall. This will exclude many academic journals and quality newspapers. But humanities researchers have a great open access alternative to publish information that AI can use – The Conversation.

In April, the Washington Post investigated how AI scans the internet for information. It listed the top 200 sites providing ‘facts’ to teach AI. The Conversation came in at 153.

Teaching is also crucial. Where AI relies on algorithms, humanities scholars train people to assess sources and evaluate information. This focus on the human, and on details over big data, will be invaluable in the AI age.

Ultimately, I am hopeful that ChatGPT will someday provide a correct answer to my question because its database of material ends at September 2021 and since then, Wikipedia has been updated to record Davidson and Mussen as News Limited’s founders. The reference provided is an article I wrote for The Conversation.

Inspired by the fact that someone else worked to put my research onto a website that is accessed by over 4 billion unique visitors every month, I recently signed up to edit Wikipedia – a new experiment.

The New York Times calls Wikipedia ‘probably the most important single source in the training of AI models’. Becoming a Wikipedia editor and publishing with The Conversation might prove to be the two most effective things that researchers can do right now to train AI. By uploading facts, information and research findings, and correcting errors and biases, we can lay the groundwork for AI systems that are more accurate but also better reflect human values and goals.

The Australian Academy of Humanities is bringing people together to explore the complexities of human-machine relations in the past and future at a symposium on November 16-17 in Melbourne. Open to all, the symposium will help us think through the risks and opportunities.