Melbourne’s new Now or Never festival—a replacement for the city’s previous Music Week and Knowledge Week—recently saw the Royal Exhibition Building filled with a number of large-scale musical events, with many focusing on the intersection between music and science. But this is not the first time the Exhibition Building has played host to a major musical festival, nor one so intensely connecting music with technology.

History of musical exhibition in Australia

The Royal Exhibition Building was constructed for the first international exhibition held in Victoria in 1880. It expanded later that decade to host an even larger exhibition commemorating the 1888 centenary of white settlement in Australia. In their displays of objects from around the world, these types of events focused on industrial progress and technological prowess, but they were also some of the most significant musical festivals held in Australia in the nineteenth century. International exhibitions were, after all, designed to show off all of humanity’s “progress” and achievements, including in the arts and culture.

Almost everything on display at an international exhibition was commercial to some extent, but the vast spaces and overwhelming number of products on show were deliberately and densely curated to dazzle visitors into losing sight of this promotion of consumption. The presence of art, and particularly music, also helped establish a grander narrative that these exhibitions were about “humanity”, not just selling goods.

Musical objects were displayed at many international exhibitions through the nineteenth century, with vast halls filled with the latest instruments and technologies. Alongside exhibits of now-common instruments were items that may appear bizarre today.

New inventions demonstrating the cutting edge of musical experimentation included self-turning music stands, machines for transcribing music, and a violin case that could be converted into a life-preserver (perhaps useful in case of shipwreck). Also popular were novel instruments, such as the Dulcitone, triplex euphonoid piano and the organo-piano—all variations on the standard piano with changes to their resonant materials—or the dramatic Pyrophone and Electric Singing Candelabras, which produced sound through burning gas.

Shaping Australia’s musical identity

No object, however, better represented the intersection of art, technology and commerce at these exhibitions than the piano itself. With a complex construction of thousands of moving parts, pianos made for interesting mechanical exhibits. As large objects they could accommodate conspicuous styles of Victorian decoration. But their association with the musical art-form also helped to free them from their obvious status as a commodity.

By the late nineteenth century, pianos had also become important domestic objects as amateur music-making increased. As Edward Rimbault described them in 1860, the piano was “the ‘household orchestra’ of the people”. This was even more strongly the case in Australia, where the piano could also represent a geographically distant European musical tradition.

French journalist Oscar Comettant—visiting the 1880 Melbourne Exhibition—joked that Australians of the era considered the piano so necessary that they would rather go without a bed than a piano; “they would sleep on the piano while waiting to complete their furnishings”.

For this reason, Melbourne’s two nineteenth-century international exhibitions contained vast courts of pianos on show. In 1888, over 100 manufacturers from around the world exhibited pianos, and these objects quickly became symbolic of social and trade relations between different countries.

German pianos, for example, were extremely popular, boosted by support from the German government and exhibition commissioners. Large numbers of staff were employed to tune, dust and spruik their wares, making Melbournians feel—according to a critic in the Horsham Times—that “the wants of Victorian buyers are very carefully catered to”. In contrast, there was much tension in the British press about colonial assessments of the English pianos on display.

These reports were laced with what Cyril Ehrlich describes as an “undercurrent of thinly veiled contempt for antipodean philistinism”. Few English makers received much attention from the Melbourne public—except for passers-by writing “shame” in the dust that accumulated on their untuned instruments. Both locals and British commentators alike were unhappy with the complacency of the British exhibitors.

The challenges of ‘exhibiting’ music.

While the display of musical instruments as exhibition objects had some public interest it ultimately left both visitors and exhibitors unfulfilled. People wanted to hear the instruments in action.

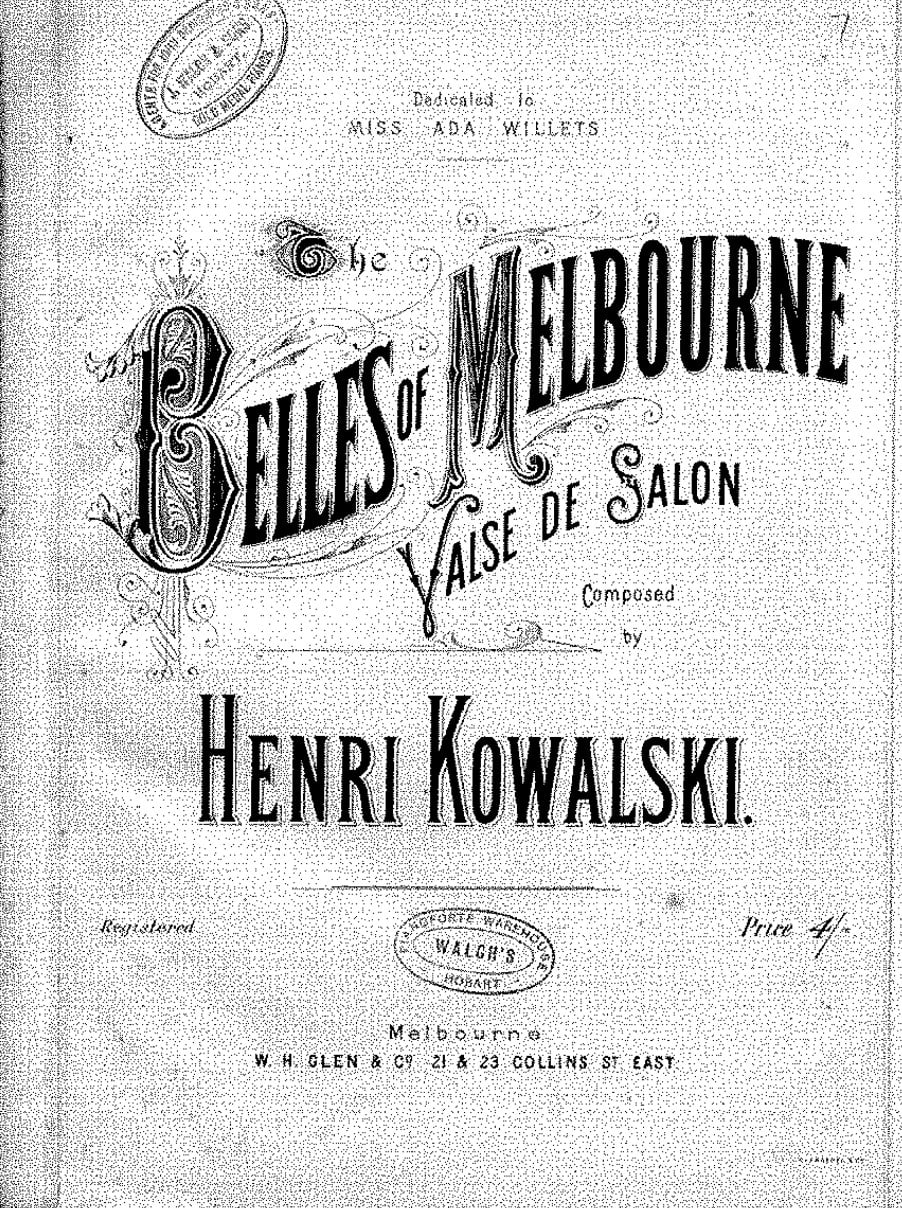

Manufacturers set to work organising demonstration recitals at their stands as advertisements for their wares. But, these recitals then also provided exhibition-attendees with opportunities to hear some of the world’s best pianists playing significant works of classical music. Through these efforts, at Melbourne in 1880, audiences were able to hear performers such as Carlotta Tasca, Alberto Zelman, and French pianist Henri Kowalski. Kowalski was particularly popular for playing commemorative pieces he’d written about places he had visited during his travels, including his Belles de Melbourne, inspired by the women he had seen on the lawn at the Melbourne Cup.

Exhibition demonstration recitals played an important role in bridging the gap between technology, commerce and art, by bringing the latest musical commodities and technology to life through the performance of both popular and “high art” music. They offered what was seen as an important corrective to the potential for exhibitions to become simply trade fairs and expanded the types of artistic and creative achievements on show at events intended to survey of the societies and cultures of the world.

References:

Edward Francis Rimbault, The Pianoforte, its Origin, Progress, and Construction (London: Robert Cocks and Co., 1860).

Oscar Comettant, In the Land of Kangaroos and Gold Mines [Au pays des kangourous et des mines d’or], trans. Judith Armstrong (Adelaide: Rigby, 1980).

Cyril Ehrlich, The Piano (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1990).