“Deliver applicable knowledge!”

This message from Canberra has become the expected norm for university research. “Applicability” shouts from every public university marketing brochure to justify the spending of taxpayers’ money. Consequently, all current knowledge production is framed and restricted by an overly idealistic forecast of and appeal to future relevance.

A quick look at research applications reveals how this forecast of “applicability” is complemented by the apparently sober, but dull and misleading ideal of writing in “plain language”. Plain language suggests that all complex matters can be presented in simple ways and implies that the use of figurative language should have no place in academic writing and research.

While presenting complexity in simple structures is a rhetorical exercise that we should all embrace, dismissing figurative forms trivialises language to the point that language becomes the equivalent of data output. Well-meant but not well-thought-out guidelines suggest academics avoid metaphors by using “plain language” when applying for government grants. But “plain language” itself is a metaphor for projecting a transparent gaze at the things themselves supposedly unhindered by “obscuring language”.

An unsettling relationship between language and politics

The politicisation of language as servile to an ideal where minds communicate without medium reflects the unsettling relationship politics currently has with language. It simultaneously celebrates its own rhetoric as it denies the relevancy of the ‘natural state’ of languages to critical academic discourses. This political strategy of rendering the medium of communication invisible has always been a successful method of subverting scrutiny.

Have we become a better society with “plain language” dictating research directions?

Any prejudicial restriction of research to a fictitious ideal of knowing what relevant knowledge is, and not just now but for the near future, inevitably leads to a consolidation of mediocrity at best or utter trivialisation at worst. If we ignore the foundational and diverse roles languages play in knowledge production, we do so at our own intellectual peril.

There is nothing wrong with striving for applicable knowledge. In fact, universities in the Renaissance period deliberated as a better scholarly ideal the vita activa, i.e. an element of applicability of knowledge to contemporary problems, around 1500. The pursuit of a vita activa for scholars was meant to replace the medieval scholastic vita contemplativa, where scholarship was invested mostly in metaphysical disputes dealing with universals.

Later, the Enlightenment was to relate universal ideas about knowledge to engagement in the public sphere. That is why Kant argued that every individual should engage in all aspects of intellectual life without tutelage and that the emerging public sphere—if uncensored—would be the decisive force for achieving ongoing improvements for future societies. Progressive enlightenment, Kant posited, would be the inevitable outcome.

Tax-payer money ‘well spent’ on theology, law and medicine

Of course, Kant was not naïve.

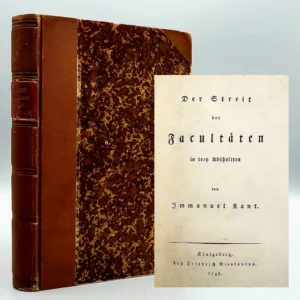

Institutions needed to play their role in the advancement of enlightened ideals. He therefore also wrote the essay “The Conflict of the Faculties”. This publication should be required reading for any policy enthusiast in Canberra or university administrator at the helm of universities today.

Published in 1798 Kant made a simple observation. The then current university structure consisted of three higher faculties, theology, law, and medicine with one lower faculty of philosophy (or artes liberales, which included Rhetoric as a central discipline). At the time, universities in Prussia (Germany) were facing increased pressure between political interests and the pursuit of a politics of truth.

And politicians, Kant observed, were all too eager to sell the worth of the higher faculties as “taxpayer money well-spent”. Theology for looking after our soul, medicine for looking after our body, and law for securing social life and the safety of our property.

In this context philosophy appeared somewhat irrelevant beyond its propaedeutic function. Kant then turned the argument around in terms of truth-seeking: if the higher faculties only dance to the tune of the politics of the day, they must be seen as corrupted in terms of seeking truth. Consequently, the only faculty not corrupted since it does not serve a political purpose is the faculty of philosophy; hence, it is the only form of engagement that can be trusted when seeking truth and nothing but truth.

Do we trivialise our most essential skills?

Given the exponential diversification of disciplinary knowledge during the 19th century due to the extraordinary rise in the empirical sciences, Kant’s dream of the foundational role of philosophy for all knowledge production could have been over before it began.

Nonetheless, two things have stayed with us since then that are worth repeating here: the pervasive dangers of politicising knowledge production in general, and of trivialising our most essential cultural skills – speaking, reading, and writing – that all entail language competency beyond the capacity of deciphering “the” alphabet and expressing ideas in “plain language”.

So where to from here? From a historical and philosophical perspective, we should examine more seriously and with greater curiosity, what this supposed ideal of “applicable knowledge” entails within the history of ideas and concepts. But this is something that will only bear fruit if more voices are considered beyond English pragmatism and a political enthusiasm for utilitarianism.

From a language perspective, I don’t think it is alarming to suggest that European languages and their respective knowledge traditions are gravely threatened in Australia. Not in everyday life, but in academic discourse.

When the German scholar and scientist Georg Christoph Lichtenberg travelled to London in the 1770s he remarked upon his return that English scholars close their books too soon while German scholars read them too long. Both ways, he concluded, have their own value and meaning in this world.

I believe that we have for much too long now only valued the first part of Lichtenberg’s observation.