I am currently sitting on the terrace of a Melbournian café, sipping a lemonade, and wondering how to explain to my students of French that a language is a living, dynamic entity that constantly evolves over time.

Indeed, the proliferation of borrowings from English (or anglicisms) in the French vocabulary, particularly in the cutting-edge sectors that are supposed to determine our future, gives rise to debates and even concern. Is the French language in danger?

Anglicisms are more frequent where French is in daily contact with English, as in Canada, particularly in Montreal. Yet in France, according to Henriette Walter, of the 35,000 words in everyday use, over 13% are of foreign origin. Of these, 25% come from English, i.e. 3% of the 35,000 words.

The threat to French does not seem so bad but I still want my students to use correct French words, when available. For example, I would rather my students use courriel, a portmanteau word created in French-speaking Canada (blend of courrier + électronique), instead of e-mail.

Loanwords: borrowing from other languages

Languages borrow from other languages. French has long served as the donor language par excellence in the history of English, since before the Norman Conquest.

Julia Schultz’s study of the Oxford English Dictionary, widely regarded as the accepted authority on the English language, demonstrates the continuing influence of French on the English lexicon.

According to Philip Durkin, 20% those words that entered English in the Middle English period (1066-1500) came directly from French (including Anglo-French), while 13% more referred to both Latin and French.

Words like chance, change, foreign, peace, poor, are all borrowed from Old French. Yet after 1500, the numbers of loanwords fall dramatically, with a resurgence in 19th and 20th century due to technical and scientific words, in particular in the fields of cuisine, diplomacy, fashion, the fine arts and society. For example, the enigmatic expression Maître d’ means a head waiter. Although Mayday sounds typically English, the etymology in the OED reveals that it represents the pronunciation of the French phrase ‘[venez] m’aider’, ‘help me!’.

War and conflict facilitate language change

Sadly, many French words relating to war and military entered English between 1903 and 1980 (Schulz, 212). My study of Australian trench journals published during the First World War led me to some surprising discoveries.

The humorous take on French by our diggers created unusual words, such as plonk, a colloquial term for cheap wine, an incorrect pronunciation of blanc (as in vin blanc). I was particularly struck by Napoo, an interjection used daily by soldiers, used to indicate that there was no more of something or that something or someone had gone: this is a very (funny) approximative rendering of il n’y en a plus or il n’y a plus (‘there is no more’).

Julian Walker’s study Tommy French elucidates the jocular form San Fairy Ann: “San fairy ann’ (often written as a single word) was occasionally shortened to ‘snaffer’ or varied as ‘Aunt Mary Ann’, ‘Maggie Ann’ or ‘Sally Fairy Anne’”. Meaning a resigned acceptance of a state of affairs, this phrase renders the French ça ne fait rien (‘it does not matter’), using humour to regain control of a desperate situation.

Meaning one thing and something completely opposite

But French itself has very strange items in its lexicon.

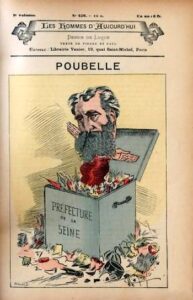

Isn’t the memory of Eugène-René Poubelle (1831-1907), a very serious and dignified statesman, still alive through waste bins?

French is so versatile that a word, along its lexicological journey, can mean one thing and its opposite.

The common word Merci was used in Old French in the expression: crier merci. It meant ‘to beg for pardon or forgiveness’ – and mercy entered the English vocabulary with this meaning. It is now used in French to express gratitude or appreciation towards someone for a kind gesture, assistance, or gift: ‘Thank you’.

The word Rien meant in Old French ‘something’, or ‘someone’. It now means ‘nothing’.

French is also full of false friends—by that I mean English words (or words that look or sound English) which have a different meaning from their original one: baskets are not baskets, but sneakers; foot is not a limb, but a sport; a brushing is a blow wave; and a parking is a car park. How confusing!

Etymology reveals surprising stories of what I would call boomerang effect. For example, the English word court, borrowed from Old French cort, court, now spelled cour, bounced back and is now used to describe a tennis court.

According to the OED, the word budget, comes from the Old French bougette (‘a small leather pouch’) and was used from 1733 for the statement of expenses of revenue: the Chancellor of the Exchequer, in presenting his annual statement, was formerly said to open the budget. French borrowed it back in its economic meaning in 19th century.

‘Soo la voo’—a modern mingling

French and English continue to intermingle in interesting and diverse ways. A recent viral TikTok video featured a mispronunciation of “C’est la Vie” as “soo la voo”. The phrase was quickly picked up by the internet as a tongue-in-cheek way to express the phrase, (with added ironic resignation), which quickly inspired a range of tote bags.

‘As the French say, “soo la voo”, or whatever.’

In sum, French had a profound effect on English vocabulary, I say to myself, as I sip a swig of lemonade at the café terrace – and yes, the three words are borrowed from French.

The famous writer Alexandre Dumas, the father of the three musketeers, had his hero D’Artagnan visiting London in 17th century say: ‘I don’t understand much English, but since English is just mispronounced French…’.

It seems that English translators found this viewpoint controversial: they carefully suppressed this sentence in their translation into English.