Mutiny on the Batavia

It was one of the most gruesome sagas of Australia’s early European history: the massacre of more than a hundred men, women and children by mutineers on a remote, inhospitable island following the shipwreck in 1629 of the Dutch East India vessel Batavia.

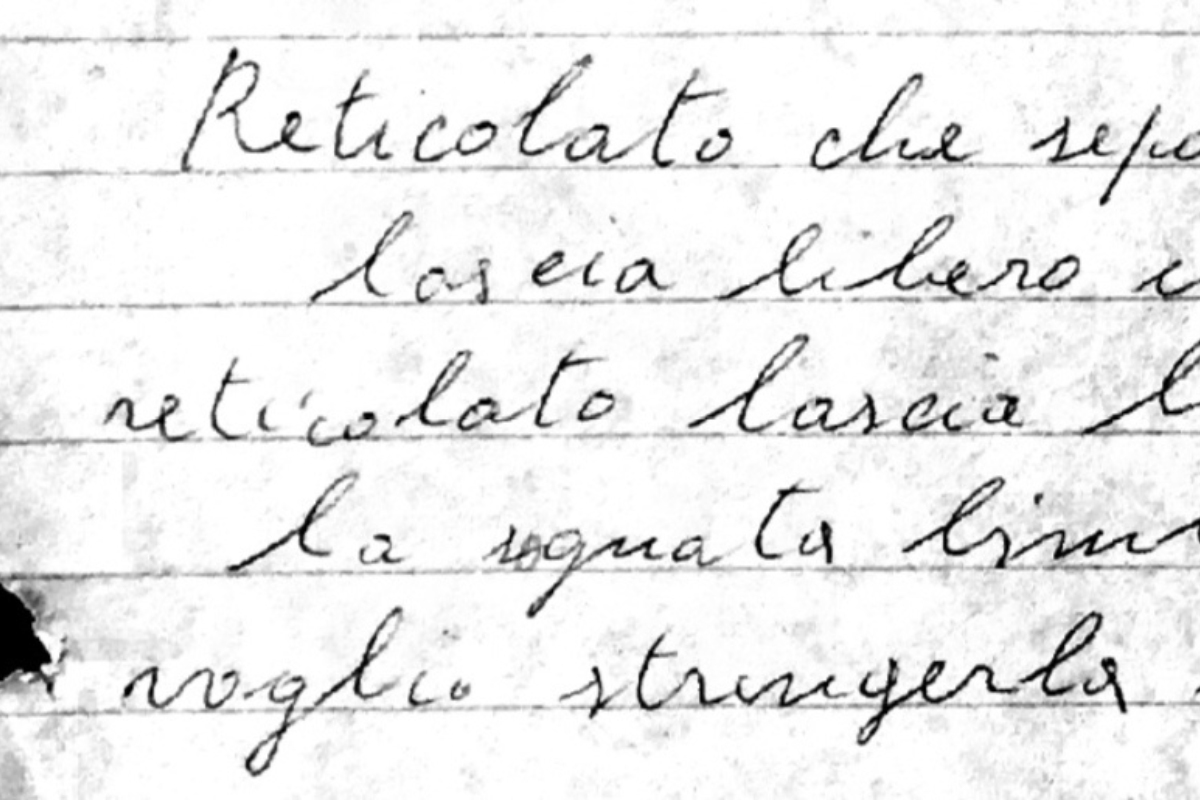

The bloody events, which unfolded off the coast of Western Australia, have long been notorious, recorded in a journal kept by the Batavia‘s Commander, Francisco Pelsaert. Over the past half-century, the work of archaeologists, anthropologists and historians has added nuance and detail to the story, uncovering new information about the murderers, their victims and the survivors.

The research has also illuminated the important role played in Australia’s exploration by the Dutch East India Company (Vereenidte Oostindische Compagnie, or VOC), whose officers mapped the continent’s coastlines – and who documented the first European encounter with Aboriginal people, at Cape York, in 1606.

Four of the VOC’s ships, using the Roaring Forties trade winds to shorten the voyage to Indonesia’s spice islands, were wrecked off the treacherous Western Australian coast. They include the Batavia, which was travelling to the Dutch colony of Batavia (now Jakarta) when it hit a submerged reef in the Houtman Abrolhos Islands, north of present-day Geraldton.

Of the 340 passengers and crew, forty died in the shipwreck. Another 115, at least, were systematically killed by mutineers led by a high-ranking merchant sailor, Jeronimus Cornelisz.

Cornelisz plotted, unsuccessfully, to seize Pelsaert’s rescue vessel when the latter returned from Batavia – the Commander had, remarkably, managed to sail there in a longboat to fetch supplies and water.

Surveys, settlers & excavations

The Batavia lay undiscovered until 1963. During the 1970s, Australia became a global leader in the emerging field of marine archaeology, as archaeologists and conservators from the Western Australian Museum comprehensively investigated seven European shipwrecks, including the Batavia.

The survey, excavation, recording and conservation techniques they developed are still used around the world today.

Western Australia also passed the world’s first legislation to protect underwater cultural heritage, in 1964, with the Commonwealth following suit in 1976.

Excavations of the Batavia recovered part of the hull, as well as cannons, navigational instruments and silver coins. More recently, fieldwork has focused on the islands where the survivors lived as castaways: the first Australian sites occupied by Europeans.

Using remote sensing techniques, Australian-Dutch teams have found traces of camps and unearthed sixteen skeletons from mass graves, along with musket balls and scraps of military clothing. On one island are the remains of a scaffold where Cornelisz and others were hanged.

Two mutineers were set ashore on the mainland, never to be heard of again; they were Australia’s first permanent European settlers.

The legacy of Australia’s worst serial killer

Isotopic analysis of the skeletons has yielded insights into the lives of the sailors, soldiers and civilians who travelled on the Batavia, including their diet, health and home countries. (The latter included the UK, France, Germany and Scandinavia.) Some bones show signs of stab injuries.

Innovative results of the research have included an exhibition in 2017 at the University of Western Australia which saw artists collaborate with archaeologists and scientists; and a virtual reality simulation of Beacon Island, where most of the Batavia‘s survivors were marooned.

Researchers have engaged with local communities on projects such as the five-year, award-winning Zest Festival, a community arts event in Kalbarri, Western Australia, celebrating the town’s connections with the VOC.

Work continues on Beacon Island, where more human remains are likely to be uncovered – victims of Cornelisz, possibly Australia’s worst serial killer.