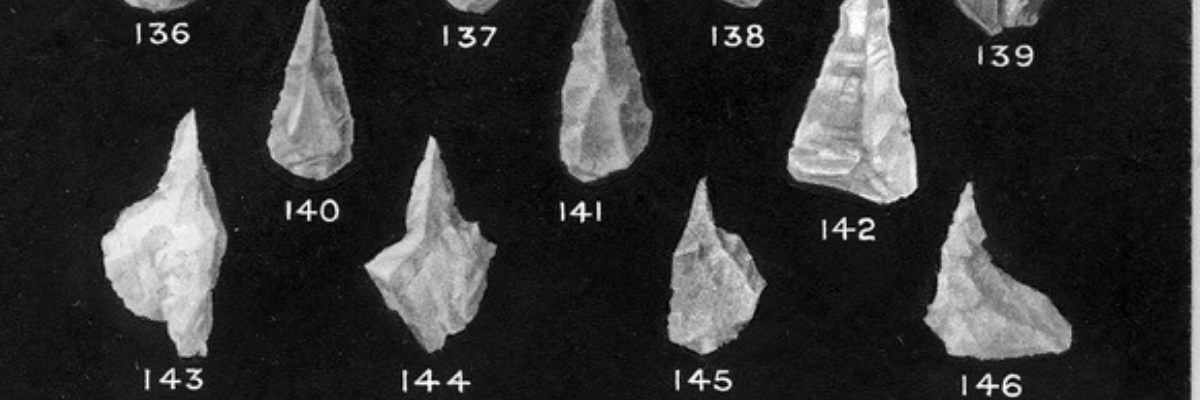

Introducing microliths

They’re not much to look at – just small chunks of sharpened rock – but the carefully crafted stone tools known as microliths tell us much about the social, cultural, technological and economic life of Australia’s first peoples.

First discovered in Australia in 1901, microliths have been found at archaeological sites across the continent – and, for more than a century, debate has raged about their age, origins and uses.

For a long time, the expert consensus was that they were just a few millennia old, used for only one purpose, most probably as spear tips, and introduced from Asia. These assumptions reinforced notions that Aboriginal societies lacked innovation, changing little over thousands of years.

In recent decades, Australian researchers have upended that consensus, establishing that hunter-gatherers in Australia were fashioning these types of tools at least as far back as the Ice Age, before 10,000 years ago, and linking a flurry of microlith manufacture to climatic changes, to which the locals adapted.

A history of innovation

They have also demonstrated that Australia’s earliest inhabitants were highly resourceful, using these pieces of flint or chert rock for multiple tasks, including hunting, butchering animals, trimming duck feathers, making bone tools, working wood, processing plants, and preparing animal hides, possibly to be sewn together.

Earlier (and even some recent) studies had suggested that microliths – also known as backed artefacts or backed blades – appeared in Australia about 4000 years ago, at the same time as the dingo, with both possibly originating in India. (“Backing” was the shaping technique used to create a thick, steep-angled back.)

Peter Hiscock and Val Attenbrow rewrote that timing in the late 1990s and early 2000s when they discovered, during fieldwork at three rock shelters in the Upper Mangrove Creek area on the New South Wales Central Coast, microliths dating from 6200 to 9500 years ago. Backed artefacts more than 15,000 years old have since been found at Cape York and the Gulf of Carpentaria.

Whether the technology was invented locally or imported remains unknown. Microliths have also been unearthed in Africa, Europe and Asia. In Australia, they had disappeared by the time of colonisation.

In research published in 2006, Gail Robertson revealed how versatile these tools were. She analysed the used edges of microliths from the New South Wales Central Coast and western Queensland, as well as organic residues from the materials they came into contact with, such as plant fibres. She ascertained that they were employed to cut, scrape, incise, drill and pierce, as well as to punch holes, with many individual specimens used for multiple tasks.

Lessons for the climate crisis

Previously, it was believed that the tools were used mainly as spear tips – a theory reinforced by the discovery of microliths lodged in a 4000-year-old man’s skeleton unearthed at Narrabeen, in northern Sydney, in 2005 – or for ritual scarring.

Like people today, Aboriginal hunter-gatherers experienced a changing climate – including unusually cool, dry conditions between about 4000 and 1500 years ago, which would have complicated the task of finding food, and maintaining social connections. This was also when microliths appeared in abundance. Researchers suggest the tools were manufactured in greater numbers in order to more efficiently exploit available resources. Perhaps there are lessons in this for us today.