Throughout most of human history, the mass of the population of our planet could neither read nor write. In the Ottoman Empire, for example, 98 per cent of the rural population was illiterate until the early twentieth century.

Anthropologists consider that in traditional societies, most people lived ‘on the margins of literacy’, but they write, as I do, from the perspective of ‘graphocentric’ western intellectuals, who inevitably privilege the written word over oral transmission.

The unbiased perspective though is that illiterate readers have engaged in literature for centuries. The oral culture of the poor has assisted the diffusion of literature of all kinds.

The original audiobook

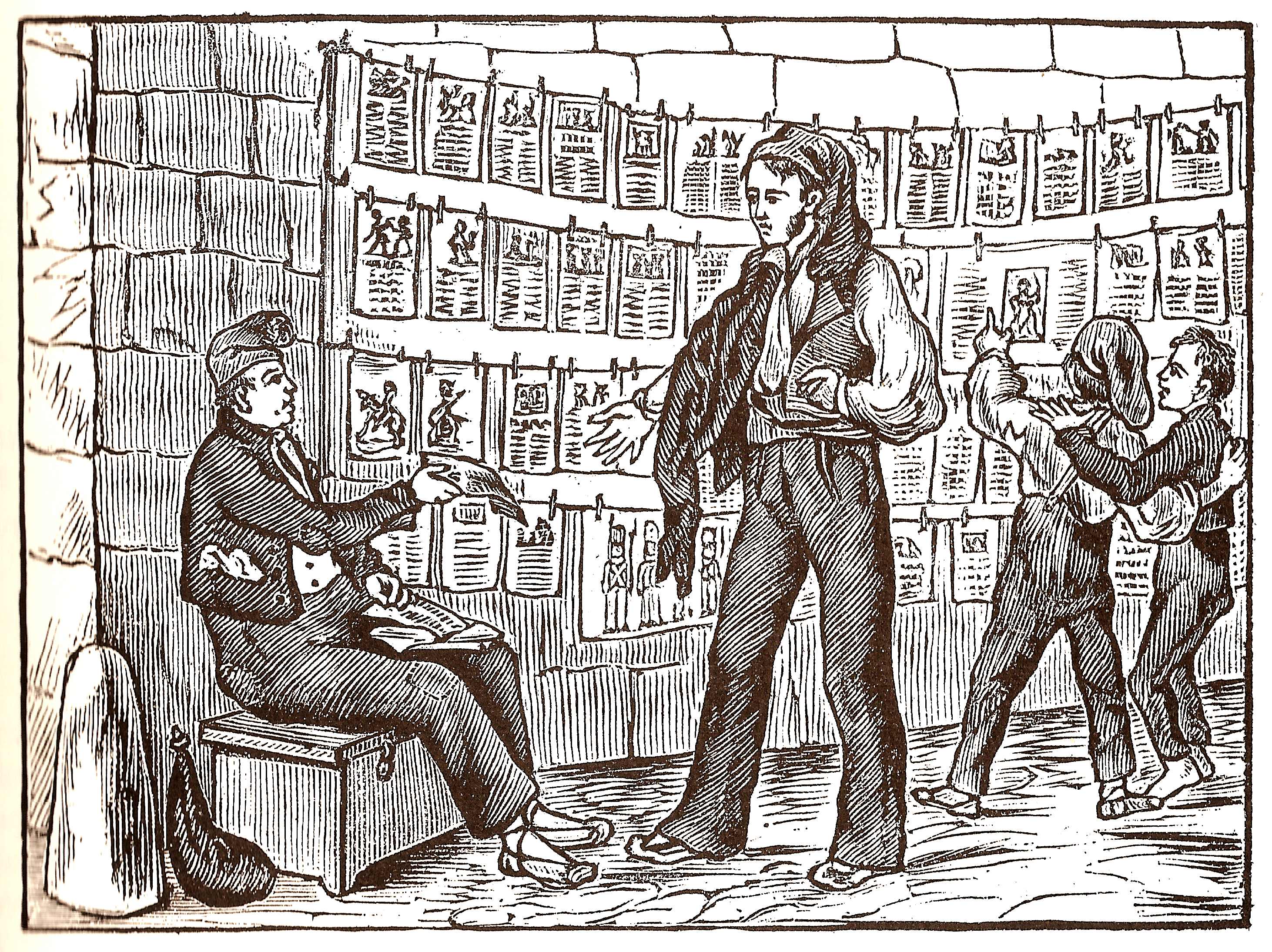

In early modern Spain and up to the nineteenth century, popular romances in the form of eight-page brochures (pliegos de cordel) were sold by blind itinerant peddlers. They memorised the texts and sang or recited them at street corners, to guitar or violin accompaniment, to advertise their stock. They identified what they were selling by touch, or with the help of an assistant.

These blind bookselling peddlers were an early form of popular mass media.

The oral reading tradition was alive and well in nineteenth-century Europe. It only required one reader to create a crowd of reader-listeners, as in the ‘Penny Readings’ of Dickens and Tennyson which delighted the Victorian public in Melbourne and elsewhere.

Literature: an important part of work culture

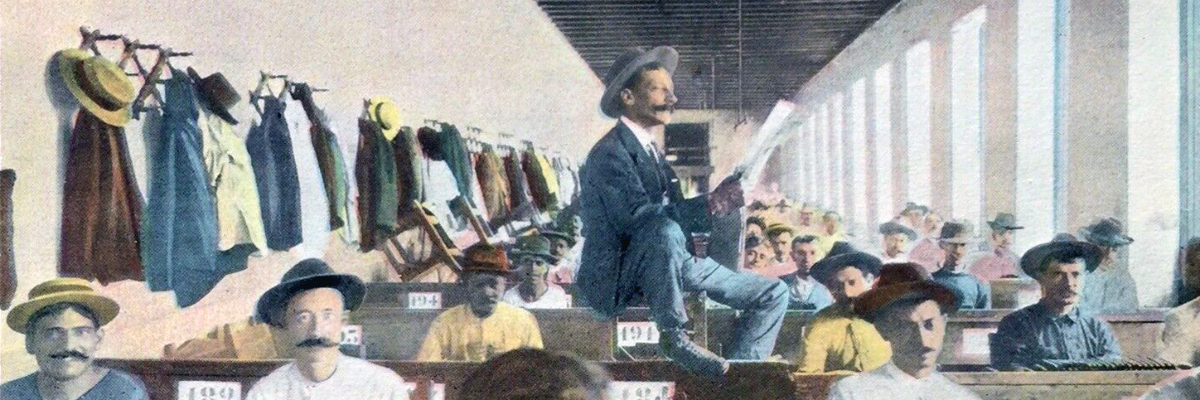

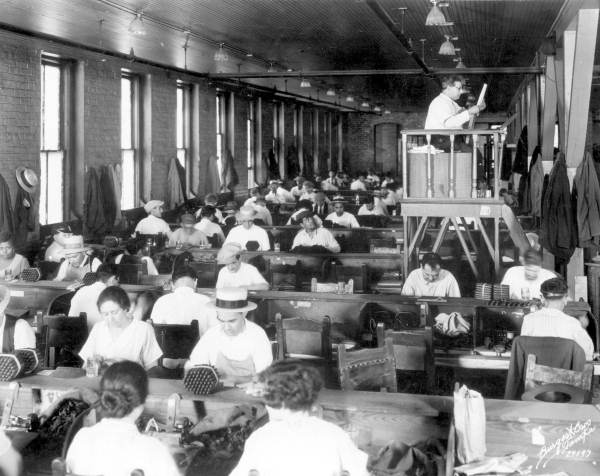

The workplace, too, was a site of collective reading. In the United States, cigar factories employed a public reader during working hours to ensure a calm environment and high productivity.

The tradition of the lector originated in Cuba in the 1860s but was brought to Florida by immigrant workers in the new cigar factories of Key West and Tampa. Here, the reader sat on a platform above his fellow workers reading papers and books aloud in Spanish. The reading material, selected by the workers’ vote, included left-wing newspapers and French and Spanish novels. Cervantes, the most important and celebrated figure in Spanish literature, was a staple.

‘No year passes in any Havana cigar factory’, wrote one reporter in 1905, ‘without a reading of Don Quijote’.

Workers were prepared to go on strike in defence of this collective reading tradition. Employers tolerated the readings for the sake of peace and to boost their workers’ concentration, but they were afraid of political radicalism and preferred to control what the lectores read. In 1931, after a decisive strike, Tampa employers secured the abolition of the lector. Until then, reading aloud was an essential part of workplace culture. Thereafter, the radio replaced the lectores.

Reading & writing: a family affair

One family member or a single individual in the neighbourhood could effectively connect an entire family group with the world of reading and writing, writing letters to absent loved ones, and reading aloud the letters received.

Letters home from emigrants, like letters home from soldiers at the front in 1914-1918, were family property and had a wide audience that was not necessarily fully literate.

When one Italian prisoner of war wrote home to Monteleone, near Spoleto, his postcard became public property. In a letter to his son, the father reported that the entire community ‘came to give me their congratulations and they all gave me their greetings, beginning with the mayor, the whole village got to know of your postcard, and everyone sends you their greetings and they share my happiness at having received your news’. It did not matter if some villagers could not read the postcard: letters home were written in order to be read aloud.

The delegation of writing

The semi-literate commonly participated in reading and writing by delegating the task to a third party.

We sometimes refer to delegated writers disparagingly as ‘scribes’, but this term is inappropriate insofar as it implies a purely mechanical act of transcription. Delegated writing was a collaborative and dynamic process, in which the writer took initiative to shape and censor what the client wished to say.

The ‘scribes’ observed by sociologist Judy Kalman on the Plaza Santo Domingo in Mexico City served customers who were not illiterate, but who valued a formal letter, couched in the language appropriate for addressing the administrative authorities. Delegated writers can be seen plying their trade today in many city squares throughout the developing world.

Three common kinds of delegated writer can be identified:

- the professional writer, consulted by both literate and illiterate customers for drafting official documents

- the local notable, perhaps a priest, a doctor, the mayor or a schoolteacher who could assist those unable to write, especially in rural areas, and

- the family friend or relative, who was enlisted for more intimate reasons such as personal correspondence.

The last example, the obliging friend or relative, was the most common, enlisted perhaps for a love letter, or for communication with an absent family member in prison, in the army or who had emigrated.

With the help of more experienced friends and companions, illiterates and semi-literates have always participated in literary culture.