Cognition for the classics

The dramatic tales of war, heroics, adventure and adversity during the siege of Troy and its aftermath, recounted in the Iliad and the Odyssey, continue to captivate readers and audiences, inspiring plays, films, novels and poems, as well as new English translations.

Australian classicist Elizabeth Minchin has uncovered new layers of meaning and contemporary relevance in the two epic poems attributed to Homer, by applying the insights of modern cognitive psychology and linguistics to the narratives, themes and characters.

Minchin’s pioneering research was motivated by two questions. Why do these works – the oldest in the Western literary canon, dating back at least 2500 years – have such enduring appeal? And how did Homer create such lengthy (Iliad runs to nearly 16,000 lines, Odyssey to over 12,000), richly detailed and poetic works in an era before writing?

Mind over matter

Homer composed the poems as he performed – sang – them for an audience. (They were later transcribed into text form.) In her acclaimed 2001 book Homer and the Resources of Memory, Minchin argues that cognitive studies on memory illuminate the everyday techniques that allowed Homer and poets working in the same tradition to perform at such length.

One of the Iliad’s showpieces, the Catalogue of Ships, lists the 175 locations on the Greek mainland and islands from which twenty-nine contingents of men joined Agamemnon in his expedition to Troy. In order to relay them all, Minchin writes, Homer would have used spatial memory, formulating a cognitive map to guide him from place to place.

He also drew on episodic memory – stored sequences of everyday actions – when relating, for instance, detailed preparations for a barbecue meal: from the slaughtering of sheep to cubes of meat being salted and slipped off skewers. As for his audience, they used visualisation to envisage and relish his descriptions of Achilles’s elaborately decorated shield.

In her 2007 book, Homeric Voices, Minchin applies discourse analysis – the study of how language is used to communicate – to scrutinise the spoken words of the main protagonists, illuminating their personalities and their world.

She also explores verbal interactions – such as when Telemachus, Odysseus’s son, rebukes his mother, Penelope – through the prism of gender, giving voice to less conspicuous female characters and validating their viewpoints. Through Penelope’s words, for instance, we perceive the emotions of a woman desperate for her husband to return from war.

Enduring legacies

The interdisciplinary approaches instigated by Minchin, one of Australia’s first female Classics professors, have influenced Homer studies and have been adopted by scholars studying other oral traditions including Greek tragedy, Biblical narratives and Indigenous storytelling.

The way that the story of Troy still engages people around the world, and the poems’ status as cultural touchstones, are evident from the flood of works they have inspired: from the wartime poetry of Rupert Brooke and Wilfrid Owen, to contemporary novels by David Malouf, Margaret Atwood and Alice Oswald, and films such as Wolfgang Petersen’s Troy.

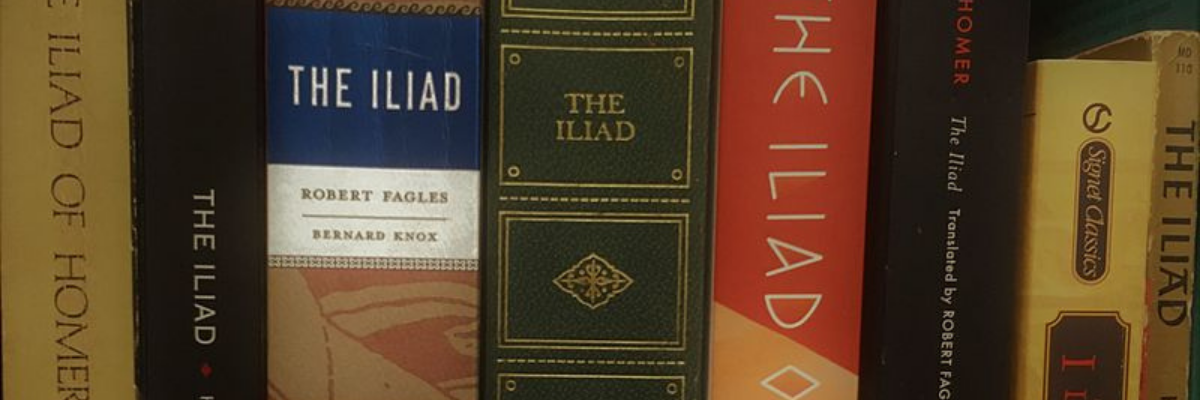

Recent years have seen female perspectives in Homer highlighted by novels such as Madeline Miller’s Circe and Pat Barker’s The Silence of the Girls (both 2018), as well as the first English translations by women: Caroline Alexander’s Iliad (2015) and Emily Wilson’s Odyssey (2017).

Minchin’s work, part of that wider trend, reveals relationships of power, status and gender in ancient Greece that have a ring of familiarity more than two millennia on. Her innovative work has not only enhanced our appreciation of the two epic poems, with their timeless lessons for contemporary society, but has also elucidated the mind of the great poet who produced them.