Forging a national identity

When Indonesia gained its independence in 1950 following three centuries of Dutch rule, neither its national language nor literary canon were as developed as a modern nation required.

There was an urgent need for both, in order to forge a national identity and culture and to unify this large, diverse country consisting of thousands of islands and hundreds of ethnic groups and languages, arbitrarily brought together by colonial power. Indonesian writers and teachers were instrumental in taking on the task but international recognition was also needed.

Australian humanities researchers played an important role in this monumental task. Newly-established university teaching departments helped to define the field of modern Indonesian literature in the new national language, Bahasa Indonesia, giving it academic legitimacy and providing necessary critical standards and training.

An Australian contribution

Scholars such as Anthony Johns, Harry Aveling and Max Lane translated Indonesian works into English, bringing the richness of this literature to the outside world, and promoting a deeper understanding and knowledge of the world’s fourth most populous, and biggest Muslim-dominated, nation.

Bahasa Indonesia, a popular version of the Malay language that had long been a lingua franca, was chosen as the national language on independence. Dutch was rejected as the language of the colonisers, while the largest Indigenous language, Javanese, was sidelined as more difficult to learn and associated with political and ethnic dominance.

For Western scholars of the colonial era, Indonesian literature had more or less halted with the colonial period. They studied sixteenth- and seventeenth-century works in classical Malay or Javanese, and took an Orientalist approach to the language, treating it as if it belonged to a long-gone era. Popular Malay was little appreciated in academia, where the hybridised Malay-language literature published in the early twentieth century was not taken seriously.

The new literature of independent Indonesia

In the 1950s, with government funding, the ANU and the Universities of Sydney and Melbourne established departments of Indonesian Studies, teaching both language and literature, in a similar fashion to European language departments. (Monash, Griffith, Flinders and Murdoch Universities followed later.) By teaching Indonesian language and its literature these departments placed the new literature of independent Indonesia alongside the traditionally taught European literatures adding weight to its status as a new national literature.

Teaching both classical and modern literature, as well as undertaking literary research and criticism, Australian researchers – supported by prominent Indonesian writers such as Idrus and Achdiat K Mihardja, recruited by the new departments – helped to re-join the severed connection between Indonesia’s literary past and its post-revolutionary present.

They also trained Indonesian PhD students and were a conduit to Australian literary journals, some of which produced special issues devoted to Indonesian literature.

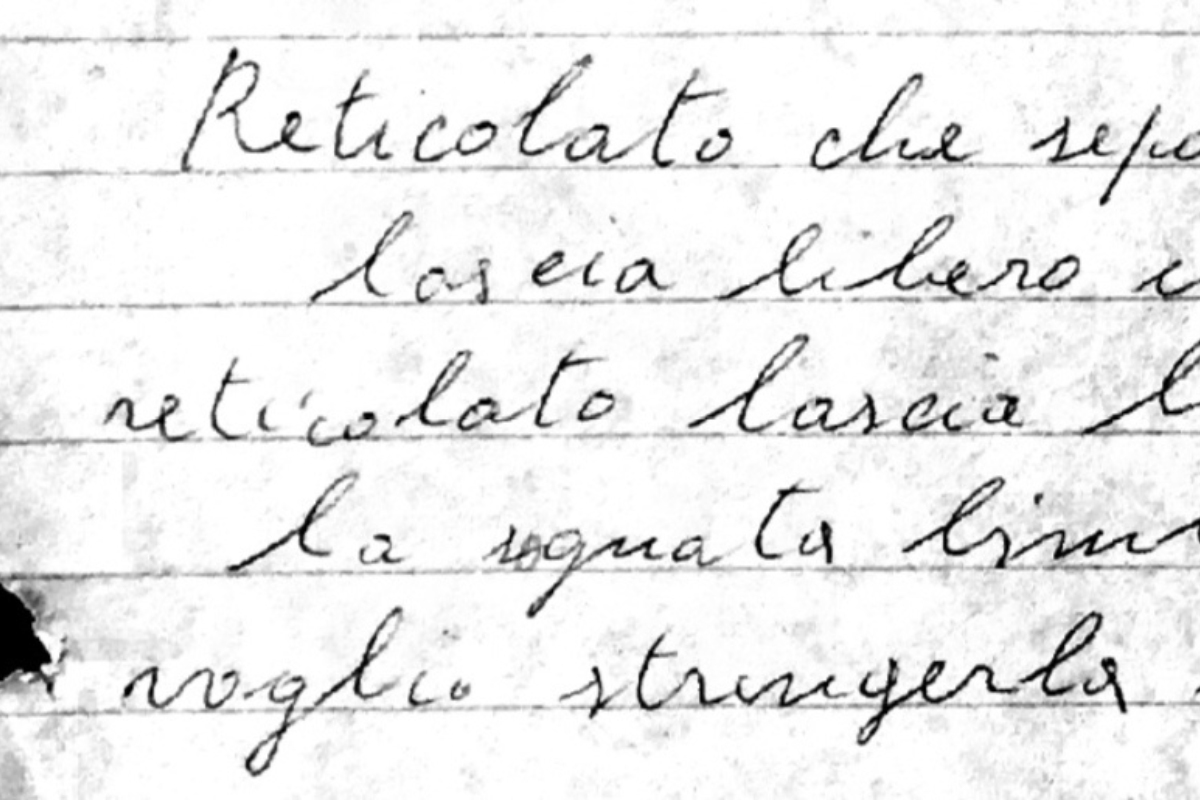

Translations of literary works, such as Secrets Need Words, an anthology of poetry penned during the Suharto regime, and novels by Mochtar Lubis and multi-award-winning Pramoedya Anant Toer, helped to elevate popular Malay as a literary language by giving it international recognition.

Closer in heart, soul & emotion

By 1990, the goal of creating an integrated national culture had largely been achieved. Modern literature, and the embracing of Bahasa Indonesia, had fostered a shared sense of nationhood, binding the country together.

Indonesia has since replaced Australia as the centre of Indonesian cultural and literary criticism. However, cultural and academic links have remained strong. Australian writers attend the flourishing Ubud Writers’ Festival, and academics are invited to Indonesian conferences.

Australian scholars have done much to demystify Indonesia for outsiders, and broaden Australians’ perceptions of their place in the Asian region.

Johns, considered a pioneer translator of Indonesian literature, was one of the first foreigners to receive an Indonesian Government award for contribution to Indonesian national culture.

As he observed in one interview:

“We’re neighbours. We’re supposed to understand each other. I thought literature could bring us closer in heart, soul and emotion.”