This year Sydney Theatre Company has an exciting new production of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, equipped with all that modern technology can offer but also relying on good old-fashioned acting and directing skills. This seems like a good opportunity to reflect on how the original text by Robert Louis Stevenson came into being and how it captured the imagination of its contemporary audience and other audiences ever since.

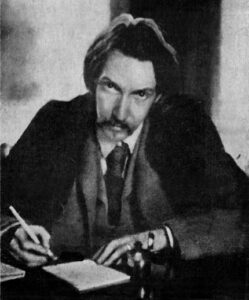

Stevenson was a great commentator on the origins of his stories—one of his most appealing accounts is the essay ‘My First Book’ in which he traces the origin of Treasure Island to a map he drew for his stepson, Lloyd Osbourne.1 Even more illuminating is the story of how The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and My Hyde came into being.

From a dream to the page

When he sailed to America in 1887, leaving Europe behind for the last time, Stevenson was met by a reporter in New York who queried him about ‘what suggested your works’, in particular Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, which had appeared very early in the previous year. Stevenson’s response may well have surprised him:

At night I dreamed the story, not precisely as it is written … but practically it came to me as a gift, and what makes it appear more odd is that I am quite in the habit of dreaming stories. … All I dreamed about Dr. Jekyll was that one man was being pressed into a cabinet, when he swallowed a drug and changed into another being. I awoke … and before I again went to sleep almost every detail of the story, as it stands was clear to me.

So intense was the interest in Stevenson across the world that the interview was reported soon afterwards in our Australian newspapers.2

Prompted by this encounter, Stevenson went on to write ‘A Chapter on Dreams’, talking about the ‘Brownies’ who worked while he was asleep, devising stories for him.3 Brownies in Scottish legend are supernatural beings who come into people’s homes at night and do their housework. Here he provides a slightly different account of the inspirational dream: ‘I dreamed the scene at the window, and a scene afterward split in two, in which Hyde, pursued for some crime, took the powder and underwent the change in the presence of his pursuers. All the rest was made awake, and consciously.’

Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde: Writing a classic

So, the dream was the starting point, but the story of how Jekyll and Hyde was actually written is even more dramatic. Stevenson’s cousin and biographer, Graham Balfour, heard it from Lloyd and told it in The Life of Robert Louis Stevenson.4

According to Lloyd, Stevenson wrote a first draft in three days but when he read it to his wife, Fanny, she responded with the objection he had written something that ‘was really an allegory … purely as if it were a story’. Shortly afterwards Stevenson called her to his room where he was lying sick with a fever and pointed to a pile of ashes: all that was left of the original.

‘Having realised that he had taken the wrong point of view … he at once destroyed his manuscript … from the fear that he might be tempted to make too much use of it, and not rewrite the whole from a new standpoint’. Continuing his account, Lloyd records that Stevenson then composed a second draft in another three days. However, this was not the end of the process. It’s clear from other evidence that Stevenson wrote and rewrote Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde over the coming weeks till he had the whole thing right—all complete within six weeks.

‘One of the most thrilling things I have ever read’

Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde quickly achieved huge success. One of the earliest reviewers, in the Norwich newspaper, The Eastern Daily Press, called it ‘one of the most thrilling things I ever read … a tale to be read at a sitting, breathlessly from cover to cover’.5 Of course, Stevenson started with a great idea (helpfully supplied by the Brownies!), and the original readers, when they started to read, were not like us. They did not have the spoiler of knowing beforehand that Jekyll and Hyde are two manifestations of the same person.

But the story’s spectacular success was not just due to a great idea. When you read it, you can see that Stevenson managed the revelation of the central secret with consummate skill.

As the story proceeds, we move closer and closer to the secret, starting with third-person narrators who relate events we do not understand and then through the first-person narrative of Dr Lanyon, Jekyll’s friend, who reveals that Jekyll can change his appearance until we finally read full disclosure of what has happened in Henry Jekyll’s own account. No wonder the original readers found it a thrilling read, as they were led on, step by step, to the final revelation of the truth. At the same time, the allegorical message is very clear.

The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde has retained an enduring fascination. Not only has the idea of a ‘Jekyll and Hyde personality’ entered the popular consciousness, but this short novel has also been one of the most frequently recreated of all books in English: adapted for theatre, film, television, radio and comics, provided with sequels, rewritten from another point of view, parodied. The list is enormous.

And now, yet again, it reappears, fittingly in Sydney, a city Stevenson visited four times, but this time it is with all the resources available to the 2020s.

Why has Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde proved so popular? It is tempting to think that the uncanny origins of the story in a dream are part of the reason—but that is probably fanciful. More likely it’s the continuing recognition of dualism in our natures, the mixture of good and evil in all of us, that strikes a key. But let us not forget the extraordinary skill with which this great writer turned a hint from a dream into a story that still resonates more than a century after it first appeared.