The Colonial Frontier Massacres in Australia, 1788-1930, led by Professor Lyndall Ryan AM, FAHA is a truth-telling project that draws on the new research field of massacre studies and digital technology to map verified frontier massacres in Australia between 1788 when British colonisation began until 1930. Professor Ryan explains how the map settles debates about how the British colonisation of Australia affected Indigenous people.

As a truth-telling project, the digital map of frontier massacres emerged from the Aboriginal history wars more than two decades ago.

Driven by debates about the nature of the British colonisation of Australia and the effect on Indigenous people, the map addresses three central questions:

- Were frontier massacres in Australia widespread or were they a rare event?

- How did they happen, and

- How can we know?

Mapping compelling evidence

Let’s address the last question first. The evidence of frontier massacre often contests the scholarly tradition of accepting first accounts for reliability.

To make sense of how this could happen, the map draws on the typology of massacre devised by the French historical sociologist Jacques Semelin.

A massacre he says, is usually a planned event rather than a spontaneous act. It is usually carried out in secret and in reprisal for the killing of an important person or theft of valuable property.

On the colonial frontier, an important person could be any colonist and valuable property is usually a dwelling, or cattle or sheep.

The most compelling evidence, Semelin concludes, is not produced in the immediate aftermath when the perpetrators subject witnesses to a code of silence but will more likely appear long afterwards when fear of arrest or reprisal has long passed.

Digital mapping offers an important tool to identify and record massacres across the Australian frontier. A digital map can visually identify the:

- massacre site

- circumstances that led to the event

- number of people killed

- date and time of day when it took place

- names of the perpetrators and victims, and

- whether the perpetrators were on foot, on horses, or on camels.

With a definition of frontier massacre as the indiscriminate killing of six or more undefended people in one operation, a coherent methodology to interrogate the sources and a star system to indicate the reliability of the sources for each incident, the digital massacre map has transformed our understanding of frontier massacres and how they happened across colonial Australia.

… frontier massacre [is] the indiscriminate killing of six or more undefended people in one operation.

Were frontier massacres in Australia widespread or were they a rare event?

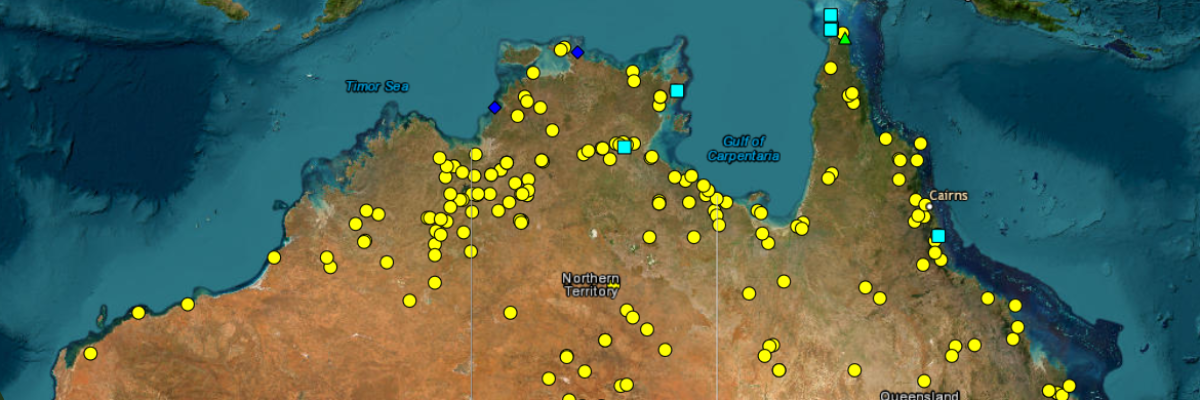

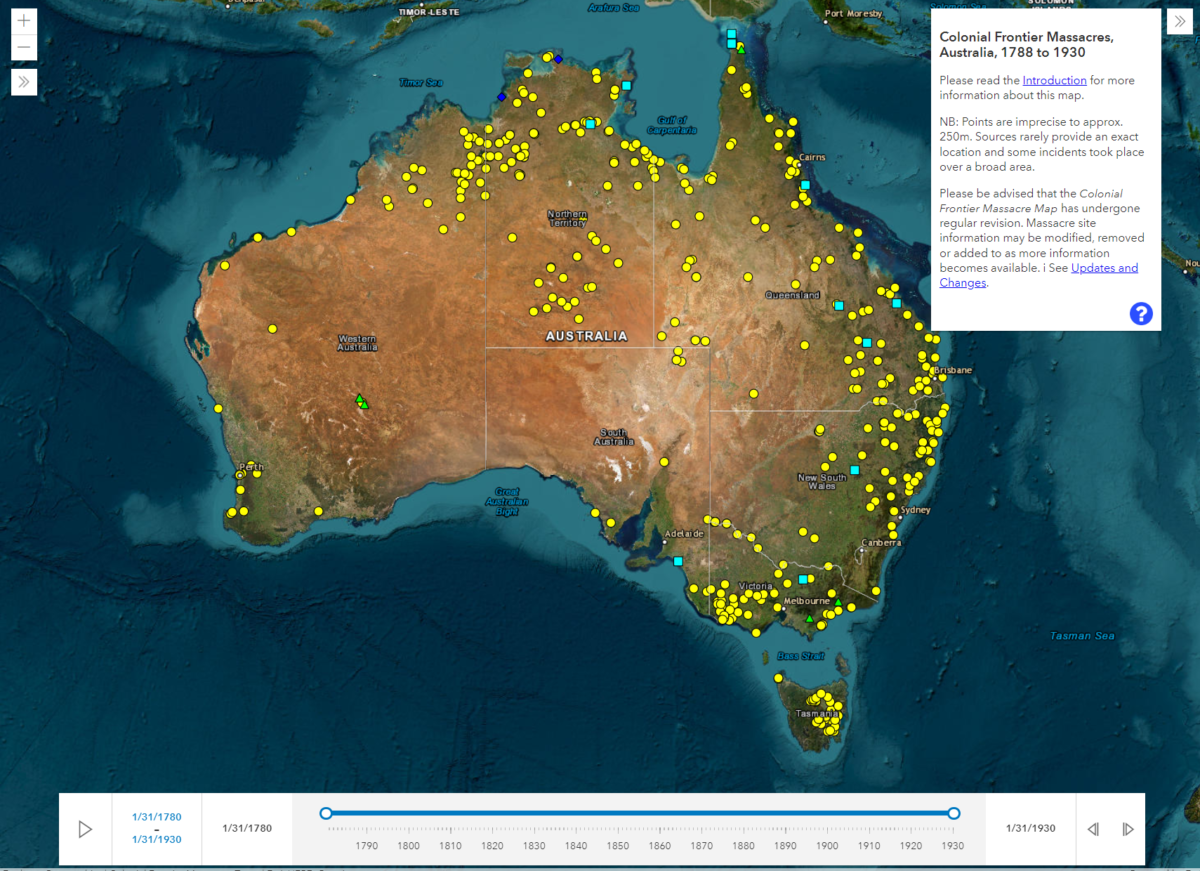

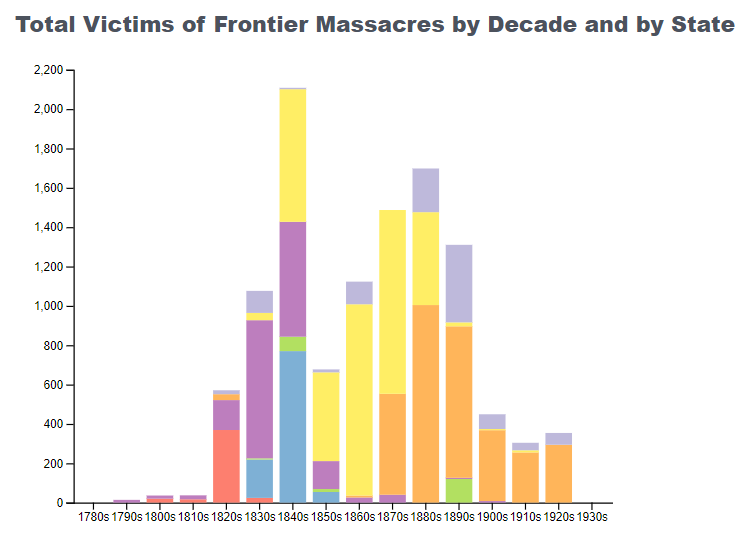

To date, the digital map shows that between 1794 and 1928:

more than 400 massacres of Indigenous people took place on the Australian frontier, resulting in more than 10,000 deaths.

Each of these massacres is identified on the map with a yellow circle.

The greatest number of Indigenous people killed in a single massacre, 300, was recorded at the Slaughterhouse Creek massacre at the Gwydir River in northern New South Wales in 1838; and at the Thargomindah Waterhole massacre in south-west Queensland in 1865.

In each case, the evidence suggests that they were carefully planned by the settler perpetrators to take place during a major ceremony in which Indigenous people participated from many adjoining regions. These kinds of massacres are known as ‘opportunity events’.

By contrast over the same period, 152 settlers were killed by Indigenous people in twelve frontier massacres. Each of these massacres is identified on the map by a blue square. These kinds of massacres are known as reprisal events. The greatest number killed in a single massacre, 26, occurred after the wreck of the ship Maria, on the south-east coast of South Australia in 1840.

Unlike settler massacres of Indigenous people, however, which were nearly always shrouded in a code of silence, those by Indigenous people, including the Maria massacre, were widely publicised.

The map also records six frontier massacres by Indigenous people of other Indigenous people, resulting in more than 100 deaths. These incidents are identified on the map by a green triangle. In these cases, the massacres may have involved traditional conflict prompted by the disruptions to land and water use and forced movements by settlers.

How did frontier massacres happen?

The map reveals that before 1830, most of the massacres were carried out by foot soldiers from British regiments posted to New South Wales, Tasmania and Western Australia to protect the frontiers from Indigenous attack. They were often part of joint operations with settlers and convicts and led by magistrates. At Bathurst in New South Wales and in the Settled Districts in Tasmania, the soldiers operated under the protection of martial law.

After 1830, the map shows that horses tipped the frontier in favour of the colonists. Mounted soldiers and police, native police, sheep and cattle farmers and their workers, could now attack Indigenous camps in daylight as well as at dawn and over broader areas.

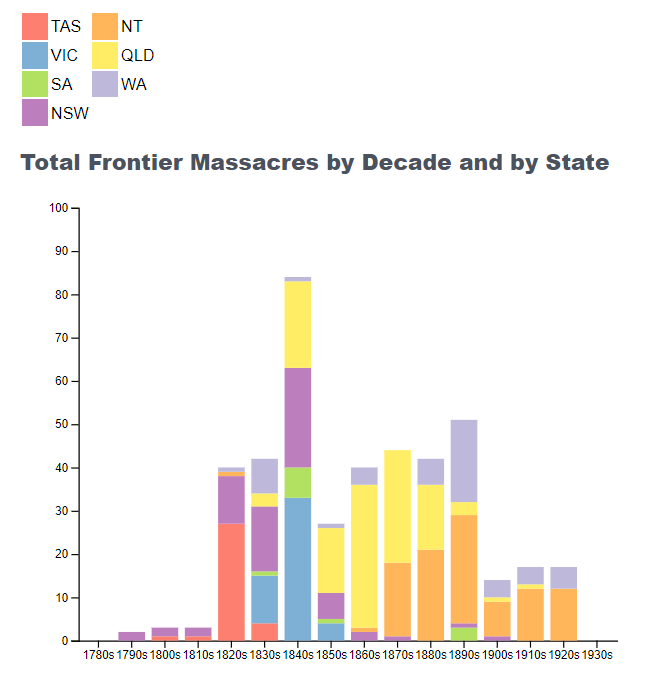

The most active decade for massacres was the 1840s with more than 100 instances occurring across southern Australia, forming ‘a line of blood’ from Rockhampton to Perth. A later broader peak occurred from the 1870s to the 1890s across northern Australia, with higher than average death tolls per massacre.

Providing irrefutable proof

Finally, despite the evidence of more than 400 massacres of Australia’s Indigenous people, they are only indicative of the probable number overall. Indeed, it is hard to find an Indigenous community that did not experience massacre. The belief by colonists that Indigenous people had no sovereign right to possess their homelands lay at the heart of every massacre they carried out.

As a truth-telling project, the map demonstrates that massacres took place on every frontier in all parts of Australia over 140 years. It also provides the irrefutable proof that Indigenous people fought for their homelands. Above all it shows that the colonial invaders and colonial and national governments were ruthless in their methods to suppress and exterminate them. With the referendum on the Voice to Parliament approaching, it is surely time for non-Indigenous Australians to acknowledge the massacres and start making amends for the past.

Further readings:

- Timothy Bottoms, Conspiracy of Silence Queensland’s frontier killing times (Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 2013)

- Stephen Gapps, Gudyarra: The First Wiradjuri War of Resistance The Bathurst War, 1822-1824 (Sydney: NewSouth, 2021)

- Chris Owen, ‘Every Mother’s Son is Guilty’ Policing the Kimberley Frontier of Western Australia 1882-1905 (Crawley: UWA Press, 2016)

- Jacques Semelin, Purify and Destroy: The Political Uses of Massacre and Genocide (London: Hurst, 2007; New York: Columbia University Press, 2009)