You’re reading this on a device that didn’t exist when you were born and on which you are, as I am, utterly dependent. What that shows, among other things, is that the truth matters and that, notwithstanding the nuances and complexities associated with a philosophical account of ‘the truth’, there are some simple but profound, even if largely unconscious, ways in which are all committed to the truth.

How so?

Because you can’t make and deploy a useable, reliable digital device without the truth mattering.

Your device doesn’t work unless the truth matters

Consider if someone at the design phase makes a mistake that isn’t caught, i.e. departs from the truth. Then the device doesn’t work. Suppose someone making a particular component of the device departs from the truth by misstating its performance characteristics. Then the people trying to fit this component into the larger array of components can’t make it interact effectively with those other components, and the device doesn’t work.

What makes a workable device possible is, of course, the technology. But what makes the technology possible is the discipline of the truth. All the different people – and they are many and various – who work on the device (and its associated technologies – networks, software, and the like) have to be oriented to the truth when they do design work, when they manufacture different components, and when they implement the larger system.

People who don’t care about the truth design or make or deploy components that don’t function.

Since, palpably, our devices do work, we can infer that all the people and processes sitting concealed within them (and elsewhere) have been disciplined by the truth. So, whether or not you’ve thought this through before, you’re happy that the truth mattered to them. You don’t want to live in a world where it doesn’t … at least as far as digital devices are concerned.

Obviously, there is a lot sitting behind all this … sitting behind the functionality of your devices. Aside from first-order issues of engineering design and manufacturing, there are the methods that scientists deploy in theoretical modelling or experimentation that are preliminary to the engineering. And these methods, crucially, are themselves designed to safeguard the pursuit of truth. (This is the domain of philosophy of science.) There are also the various ‘audit’ functions to ensure that these methods have actually delivered truthful outcomes and that we know that they have. (Peer review is an example.) Nowadays you hear about these behind the scenes truth-protective processes of method and audit under the heading of ‘Quality Assurance’.

Notice how general these observations really are.

Truth governs our economy & wider society

Notice too that the idea of a ‘technology’ isn’t just about electronic or mechanical ‘stuff’. It’s nowadays widely observed that some familiar social apparatus in effect constitutes a technology, as for example, the techniques of method and audit that I’ve just mentioned … they’re Quality Assurance technologies. To take another, and central, example: our legal system, which sits at the very heart of all the myriad transactions among businesses that are involved in device manufacture, is also disciplined by the truth.

Think about how the various component manufacturers interact with one another as corporate entities. They exchange legal as well as technical documents, binding them, e.g., to deliver so many components at a specific price, by a particular date and in accordance with technical specifications that ensure functionality. If any of those statements is false, whether intentionally or otherwise, then there may be a breakdown in the supply chain associated with the manufacturing process.

So, the sort of social cooperation that’s necessary for complex technological achievements to be realised depends on the participating parties being truthful with one another in their social, e.g. contractual, relations with one another; that technology too doesn’t work if people don’t have due regard for the truth.

This is pretty compelling, I think: neither technology nor relations between organisations work effectively unless a regard for and protections of the truth are widely acknowledged and honoured.

So why are we talking about ‘post-truth’, as if we’d ‘gotten over’ that whole truth thing?

Politics and post-truth

Consider how politics seems to work nowadays. There are some more or less reliable ‘hot buttons’ that politicians know they can push to attract attention and votes … and the effectiveness of these hot-button issues often seems to float free from questions of truth.

Of course, it’s not just politics that sometimes, increasingly?, mostly? — works by appealing to emotions rather than the truth. There is, for example, marketing of products and ideas, as, for example, with your device. We know that a lot of consumer decisions are made on the basis of emotion and, accordingly, a lot of marketing is based on identifying the hot buttons and figuring out how most effectively to push them.

(Notice, by the way, and ironically, that the systematic deployment of hot buttons itself depends on a due regard for the truth. It’s an empirical matter which buttons are and which are not ‘hot’ and that has to be discovered the same way that other facts are discovered and hence via truth-aligned approaches.)

More worryingly, with some products, with some ideas, there’s nothing more to them than the hot button.

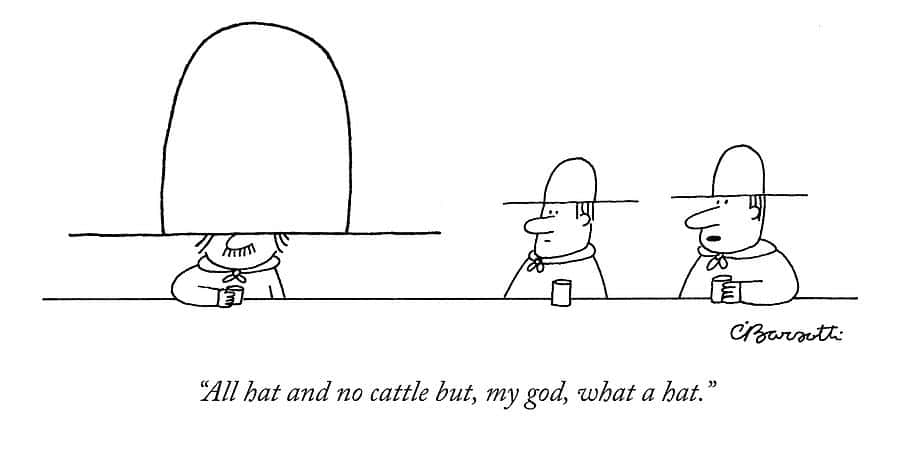

Some people think that this very thing is happening a lot in our public culture — that more and more claims that are made to attract political support or to stimulate a purchase are all hot-button and no truth (or, in the Texan idiom, all hat and no cattle). On this account, then, the public sphere is increasingly a duel of hot buttons where the truth is crowded out. If my button is hotter than yours, then I will prevail, without the truth mattering at all.

Suppose we were, at least in the related spheres of politics and marketing, in a post-truth world. What would happen? And what could we or should we do?

First of all, when claims or technologies that we rely on are not truth-aligned, they don’t work, or don’t work reliably, and so we don’t get out of our commitment to them what we committed to them in the first place in order to get. Some people worry that this is happening with democratic institutions. And that’s not just a loss of a promised something (whatever that was); it’s also a loss of innocence.

So, secondly, trust can be a second-order casualty of a post-truth substitution of hats for cattle. I can’t trust someone whose claims aren’t truth-aligned. I might be tempted to believe them based on the hotness of the buttons they’re pushing, but, if I fall for their pitch, I will be disappointed and I will be less trusting in the future … and, worryingly, I may be less trusting generally and not just less trusting of them.

Loss of trust is a worry because, of course, it’s a crucial element for any working society, either small-scale or large. Consider how much trust we routinely repose, nearly every second of the day, in people we don’t know and technologies we don’t understand.

It matters, then, whether it’s hat or cattle that are calling the shots in our society because without the cattle things don’t work and people don’t trust each other.

What can or should we do about this?

We could make a good start by not giving hostages to the entrepreneurs of a post-truth world … by recognising that, notwithstanding the nuances of insider theorisation of ‘the truth’, there is an everyday notion that is more than adequate for the defence of the truth as a lynchpin of contemporary society, culture, and technology. Insist on seeing the cattle; don’t settle for a glimpse of the hat.

Thinking about the politics more politically, we can take the hot buttons away from politicians and they’ll either stop using them or become increasingly ineffective in recruiting our support. Just as emotional appeals can crowd out appeals to the truth, so, given concerted and determined efforts, can the truth drive out appeals to the emotions.

We may be witnessing this kind of push-back against hot-button-dominated public discourse right now. Certainly, the so-called heritage media – the media from before there were social media – are gradually being emboldened to do what it has always been their democratic purpose to do … to speak in the name of truth and with regard to the truth and thereby to chill out the hot buttons that can otherwise dominate public discussion of crucial issues. And various civil society organisations are emerging to reassert the relevance of the truth … to herd the cattle rather than parade the hats.