It’s hard to explain to outsiders how homophobic this country used to be.

Tourists now fly in for Mardi Gras and images of surf life savers are sold around the world. Yet artist Jeffrey Smart once said he thought he was ‘the only homosexual in Australia’.

I am currently the Australian representative for a path-breaking global art exhibition with the intriguing name The First Homosexuals: Global Depictions of a New Identity, 1869-1930. The project explores 250 representations of queer women, men, trans and non-binary peoples between 1869-1929—before definitions of sexuality took their current forms.

The 23 scholars in the Advisory Board come from every region—including North Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia. The exhibition will highlight colonial legacies, with mainly British laws laid over other peoples’ differently nuanced concepts of sexuality. Led by the pioneer of gay art history, Jonathan Katz, this is ambitious, international scholarly research. A large exhibition will be launched in 2025 at Gallery Wrightwood 659, Chicago, wholly funded by the private foundation Alphawood.

It has been a revelation and an honour to see the extraordinary work created by queer women, men and trans before the 1930s. Most remarkable are the nonbinary representations. I was astonished by the 26-metre temple of queerness Il Chiaro Mondo dei Beati [The clear world of the blessed] (1920-1939) by Estonian artist Elisàr von Kupffer and their husband.

The show will contend that as definitions of sexuality became more prescribed, art itself grew more and more queer, contesting ‘the very terms of its existence’.

Naming the people & really seeing the artists

The history of terms describing sexuality help us understand the silences. The words monosexual, homosexual, heterosexual and heterogenit were coined by Karl Maria Kertbeny in 1868 in a private letter to ‘homosexual’ sexologist Karl Heinrich Ulrichs. These terms all related to sexual activity rather than an inherent identity (e.g. monosexual meant masturbation). Kertbeny only published the term homosexual in 1869 and his English counterpart, Havelock Ellis, used the term ‘sexual inversion’ to describe homosexuality in 1897. The word heterosexual was first published in Germany in 1880 and appeared in the USA in 1892.

Why so late? Katz tells us that a vast panoply of other terms describing different types of gender and sexuality were circulating and only after 1910 were the words we are familiar with today widely used.

All this naming is very recent. And, the appearance of new terms helped produce new art and new artistic identities.

The Australian experience

Since the early 1990s, I have been researching gay men and women in Australian art and design. It’s a hard slog, as there is scanty material and no books published on the topic. Until the National Gallery of Victoria did their sprawling but impressive Queer: Stories from the NGV Collection in 2022, no overview had been attempted. But, there were important efforts such as the NGA’s 1994 Art in the Age of AIDS and Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery’s HERE&NOW2020/Perfectly Queer curated by Brent Harrison.

We face specific challenges in securing the artworks to represent the Australian experience in The First Homosexuals. First, the exhibition focusses on painting and sculpture, when much of the queer traces reside in illustration, caricature, the decorative arts and design. Second, Australian women and men were circumspect in a nation where male homosexuality was criminalised colony by colony, with South Australia the earliest state to decrimimalise as recently as 1975. Women, too, risked losing their reputations and becoming social pariahs even if they did not face jail. Third, many loan requests have been denied.

Many Australian artists became expatriates, not simply for the lure of Paris or London, but because they could experience a radically different social existence.

We are often working with fragments or pieces that point to or suggest a queer identity that we can never ‘prove’. This does not mean that the homo-erotic and other homo-centric work they created did not impart queer meanings for audiences at the time. One challenge working in this space is ‘presentism’: reading the messy vitality of relationships and sexualities in the past from today’s perspectives. In earlier years these artists were often dismissed as ‘cosmopolitan’ or ‘non-Australian’, but now we can reconnect them to wider waves of artistic and cultural connectivity.

‘Until things change’: the time to exhibit queer art

Work made by Australian queer women before the 1930s is remarkable and plentiful. They include Eirene Mort, who designed an unconventional house to share with Nora ‘Chips’ Weston; Bessie Davidson; Grace Crowley and her ceramicist partner Anne Dangar, and Janet Cumbrae Stewart, famous for her finely finished female nudes, who moved to Italy with her companion-publicist and business manager, Miss Argemore Farrington ‘Billy’ Bellairs.

Girl with Cigarette c. 1925

Oil on canvas

Collection Bendigo Art Gallery

Bequest of Mrs Amy E Bayne 1945

99.5cm x 81cm.

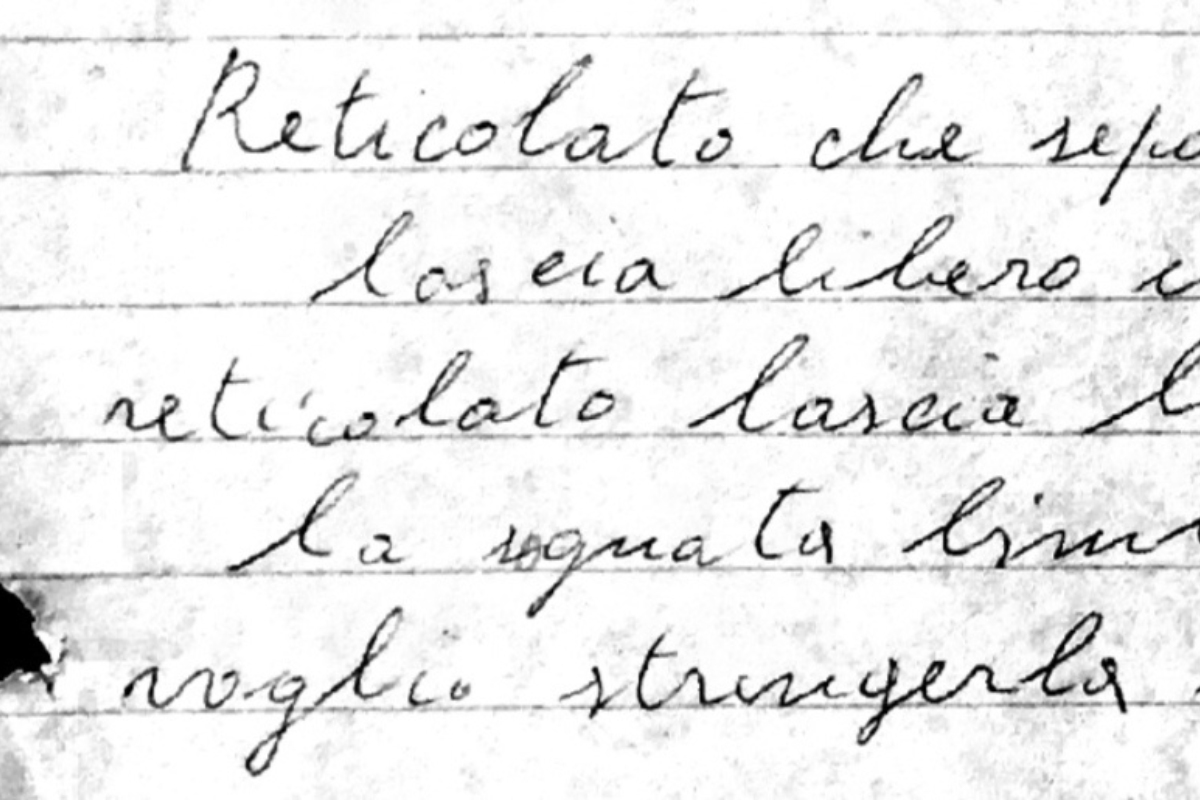

The subject is Goodsir’s partner, Rachel Dunne, known as ‘Cherry’. This piece was one of many returned to Australia by Cherry upon Goodsir’s death, with her hope the work could be exhibited when ‘things change’.

One of the remarkable portraits of Bendigo-area-born Agnes Goodsir will feature. She lived amidst the Paris lesbian demi-monde with her partner, an American woman, Rachel ‘Cherry’ Dunn. Goodsir once said: ‘I don’t know how Australian audiences will like my work – or whether they will like it at all – It’s entirely French you see’.

NGV curator, Angela Hesson, explains that Cherry had cherished Goodsir’s memory and sent important works back to Australia to ‘have them stored until things change and they can be exhibited’.

That time is now.

Her works were generally in Australian gallery storage until Bendigo Gallery director Karen Quinlan gave them due recognition in 1998. The inclusion of Goodsir in The First Homosexuals will be a literal coming out/coming home story, with her astute portraits of the new woman of Paris/the Parisienne brought fully into international circulation.

The men are frankly more challenging as they left fewer traces. Charles Conder and Rupert Bunny were ‘queer adjacent’, friends with Oscar Wilde and his circle, if not queer themselves. Sydney Long and Elioth Gruner are significant: Long’s By Tranquil Waters (1894) will feature.

The married, Bertram McKennal (King George V’s favourite artist) created astonishing work such as the ephebe-like War Memorial for Eton College (1923, now NGV), which was later deemed undesirable for representing a naked youth. In 1930s London, William Dobell painted his Greek lover. Sometimes the trace survives in other ways: Sydney’s Archibald fountain was sculpted by a queer Frenchman (François Sicard), and subsequently became a cruising destination for gay men.

Homosexuality has been presented since ancient times as coming from ‘elsewhere’.

As the project presents a new and global, inter-connected history, it is crucial to our understanding of contemporary homophobia and the actions of those nations currently enacting anti-GLBTQI laws on assembly and visibility.

In late 2023, Russia judged the LGBTQI movement to be an extremist organisation. Being queer and being able to live the creative or personal life you desire is not an abstraction.