For five years in the early 1800s, a young woman by the name of Sara Baartman was exhibited in ‘freak shows’ in London and Paris—her ‘unnatural’ body placed on public display for a fee. Promoted as ‘The Hottentot Venus’, Baartman died in her mid-twenties. Her body was subject to an autopsy and dissection, conducted by French naturalist and zoologist, George Cuvier. Her distended buttocks, and elongated labia, were the focus of her display in the carnivals and Cuvier’s report on her corpse.

How did a woman born in southern Africa come to be paraded as an exhibit in Europe? What does the European preoccupation with her body, both living and dead, tell us? And why does her story continue to attract scholarly, political, and popular attention?

Her body is central to understanding each of these questions. Bodies matter.

The life of Sara Baartman

My current research explores the history of the human body including its connection to sexuality and gender and its functions as a cultural artefact. Specifically, I am interested in how and why bodies deemed unnatural and unruly are represented. And, as Sara Baartman’s story would demonstrate, interdisciplinary, comparative, and collaborative methodologies are crucial to such projects. The human body is at once a biological specimen and cultural artefact and is rich with both political and historical significance.

Baartman’s brief transnational life is inflected by European colonialism and its accompanying racism and dehumanisation, but it also reveals how the body was a key cultural artefact in the production of new forms of ‘scientific’ knowledge that underpinned this colonialism.

Baartman was a Khoisan woman, born around 1790, near the Gamtoos River, now recognised as the Eastern Cape, South Africa. She was orphaned as a child and subsequently taken to labour on Dutch European farms. Later, she worked as a maid and nursemaid in Cape Town. Then, in 1810, she was taken to London to be exhibited as a carnival or freak show attraction. Baartman was later sold and taken to France to be exhibited by an animal trainer. She died on 29 December 1815.

Her death in Paris enabled Cuvier, a senior figure at the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, to dissect her body in 1815 and publish his findings in 1817. A founding figure in the new field of comparative anatomy, Cuvier’s investigation of Baartman’s corpse would advance his theories of racial evolution.

Baartman was a victim of the fetishisation of her body in life and death by all manner of Europeans—from ordinary folk seeking diversion at carnivals to researchers advancing their professions. In Europe, Baartman was the ‘African other’ who confirmed the advanced civility of Europe and whose unruly body, displayed, painted, and ultimately dissected, justified continued, brutal colonisation.

Translating an inaccessible history

Yet, more than two centuries after its first publication, and despite the significance of Baartman’s life and death, the report was inaccessible to English-only readers until 2023. Many of the available translated fragments were inaccurate and, as snippets, they also lacked the rich context of the complete text. So, Alistair Rolls, Associate Professor of French Studies at The University of Newcastle, and I collaborated to produce the first English translation of Cuvier’s report. It was published in Terrae Incognitae in 2023.

Providing a complete and accurate English translation is important because Baartman has recently gained new attention among researchers in multiple disciplines as they seek to understand the history of science, and the production of knowledge that accompanied Europe’s colonial endeavours. And, Baartman is also important in South Africa’s post-apartheid political campaigns where calls to repatriate her remains were championed by President Nelson Mandela. This lengthy process was completed with her reburial in 2002.

Until we published our translation this year, English-only readers had no access to a key document on her life and death. Her posthumous story as Cuvier’s ‘specimen’ warrants a broader audience for all that it reveals about the knowledge underpinning colonialism and the ways that ideas about race, sex and gender are manifest on the corporeal form and make the body a key cultural artefact.

The detailed and delicate process of translating a nineteenth-century French report into accurate yet sensitive English required us to engage deeply with a text that was confronting and occasionally unsettling to work on.

How did I, an academic specialising in ancient Mediterranean societies of classical Greece and Rome, come to collaborate with a French Studies academic on a topic of this sort?

Why was this collaboration enriching?

Drawing on my earlier work, it was evident during the translation process that European antiquity continued to influence the ways that people in the early 1800s viewed and understood the human corporeal form—even while they, like Cuvier, were building new disciplines of palaeontology and zoology. My knowledge of ancient Europe enabled us to reveal the significance of the Classical world to Cuvier’s world view—allusions to antiquity are scattered throughout what is, essentially, a medical text.

Her stage name, “Hottentot Venus” was a direct invitation for audiences to connect her to love, fertility, sex and desire of the Roman Venus, albeit in an ironic, demeaning way, but Cuvier goes even further in drawing on classical allusions. For example, he compares Baartman’s body with other peoples, including Ethiopians, citing Herodotus (Fifth Century BCE), and Diodorus (First Century BCE) via Agatharchides (Second Century BCE).

How Europe’s antiquity underpinned colonialism

As a Classicist, it was clear to me that classical allusions to ancient Greece and Rome informed Cuvier’s development of the burgeoning field of comparative anatomy and how it was central to the intellectual work that accompanied colonisation. This analytical work draws from Classical Reception Studies—a field that explores how Europe’s classical antiquity has been “received” by later generations—appropriated, reconceptualized and recontextualized—and how it has shaped the history of ideas through to the present.

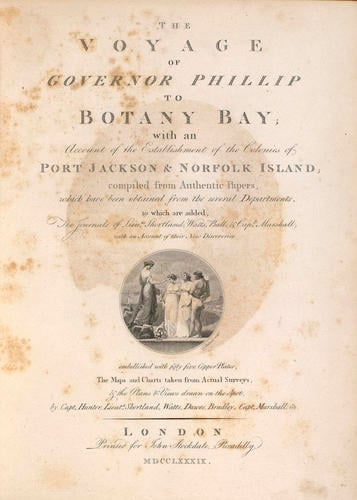

In so doing, British colonists of Australia engaged with ideas of ‘noble savages’ progressing along a civilisational path to the pinnacles of human endeavour circulating in Europe at the time. By carefully mapping such debts, the cultural historian can explore and interrogate the continuum of the ancient Greeks and Romans—for both good and bad—and to extend dialogues on colonial settlements, such as Australia and South Africa.[1] Many colonial-era works on so-called exotic and alien bodies show a distinct debt to Europe’s classical antiquity.

The frequent invocation of classical antiquity in the European presentation of foreign bodies was part of the colonising task of taming, controlling, and distancing colonised peoples. Viewers of these corporeal forms, either in carnivals, galleries, museums, or books, were participants in this organising and cataloguing of unruly bodies in a romanticised historical trajectory framed by classical antiquity.

[1] See Marguerite Johnson, ‘Indigeneity and classical reception in The Voyage of Governor Phillip to Botany Bay’ Classical Receptions Journal 6.3 (2014), pp. 402–25; and ‘Black out: classicizing indigeneity in Australia and New Zealand,’ in Marguerite Johnson ed., Antipodean Antiquities: Classical Reception Down Under (London: Bloomsbury, 2019), pp. 13-28.