More than two years ago now, in my first President’s Conversation, I talked with a passionate and thoughtful panel of scholars about the challenges of humanities teaching in times of environmental catastrophe: Dr Blanche Verlie, Professor Andrea Gaynor, Dr Tom Ford and Dr Paula Satizábal.

The President’s Conversations were convened partly as a response to the isolation of the pandemic, and listening again to the recordings evokes the feeling of academic life confined to lounge rooms, bedrooms and kitchen tables. In 2023 we have mostly emerged from the extremes of isolation. But for those that remain in academia, work structures have changed forever and demands continue to increase.

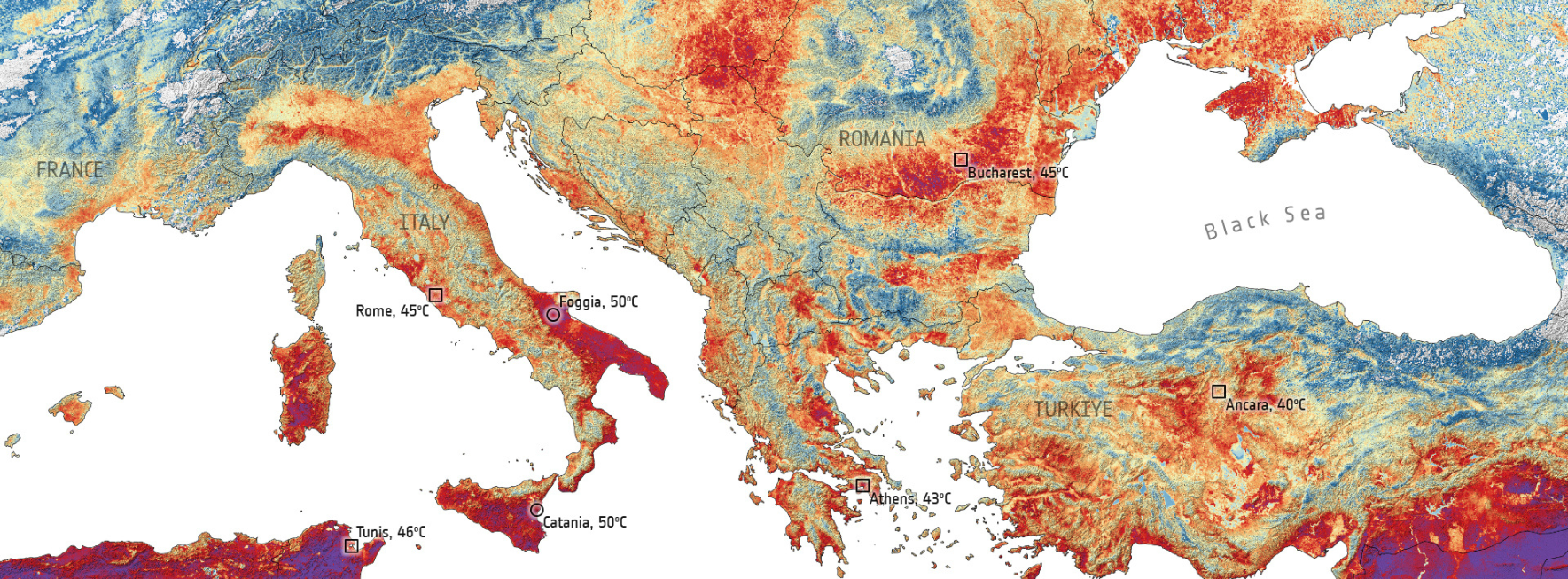

The relevance of the subject matter of ‘times of environmental catastrophe’ has only intensified with ongoing increases in greenhouse gas emissions, breaking of temperature records on land and sea, and a continued litany of extreme environmental events. The current season has seen record heat waves in different parts of the northern hemisphere, and severe fires in Canada causing diminished air quality across the northern USA – reminiscent of the choking skies of Australia’s Black Summer of 2019-20.

Lounge room offices, self-care challenges & avoiding despair

It is worth revisiting some of the key points made in that conversation. Panel members drew on their research and lived experience to emphasise the importance of:

- practices of care (for students, and also for the self) in teaching about very confronting subject matter evoking strong emotional responses, and

- empowering students to develop their skills to take action, with others, as an antidote to despair.

Panellists discussed the difficulty – if not impossibility – of establishing the necessary relationships with students, and doing that kind of teaching in the current university context. They documented the ways university business models systematically preclude opportunities for reflective teaching. Indeed many aspects of contemporary universities can be understood less as sources of radical hope and more as part of the failed business model that has driven the climate crisis.

Readers accustomed to thinking about climate change and the biodiversity crisis as environmental issues might be surprised to hear so much emphasis on work practices and institutional structures. But if the pandemic showed us anything, it is how converging crises will increasingly require us to deal with several different kinds of precarity at once. Paula Satizábal and colleagues are rethinking how to be scholars in ways that we can all learn from.

Our discussion drew out the essential role for the humanities in unpacking, and where necessary, shifting the words and concepts through which we understand the world. Two of particular relevance are environment and crisis.

Environment, crisis & the essential role of humanities

Environmental issues are still widely seen as STEM issues, including within universities. Humanities can tell the history of how the association between environment and STEM happened, and articulate alternatives. Humanities approaches elaborate the way environmental problems are human problems, and make space for worldviews that are less separationist, including Indigenous ones. Increasingly, these approaches demand a more relational understanding of the human, far removed from the individual Enlightenment subject.

Concepts of crisis and emergency are being reworked to consider what happens when multiple and converging temporalities are folded together. Converging or conjunctural crises demand complex policy and community responses and will increasingly challenge our social resources. They create ethically complex dilemmas.

In the time since that conversation, we also have a new federal government that promised much on the climate change front. There is little evidence of current decision-makers being prepared to confront the necessary scale of action. Indeed, there is a kind of green gaslighting going on – governments and companies perform a mode of action that does not solve the underlying problem but instead facilitates the maintenance of business as usual.

Fossil fuel vested interests appear to have a chokehold on Canberra and on the United Nation’s COP process. The only actions that are imagined as realistic and possible are those that do not interrupt the business of economic growth.

The increasing criminalisation of protest activities is a particularly chilling moment, allegedly justified because protests disrupt everyday life and people going about their legitimate business. As if increasing extreme weather events are not also doing that right now.

Using our unique humanities tools

Although, as Tom Ford commented, the humanities ‘don’t do anything in a nutshell’, I think there is one key area where we could focus our efforts. There is a ‘rapidly closing window to secure a liveable future‘, yet it is apparently unthinkable for Australian governments (among many others) to stop extracting fossil fuels – coal, oil, gas.

Before that window closes, we must make the necessary action thinkable, and help imagine and enact the alternative worlds that action will bring into being.

We have many tools to do so. We can challenge cultural denial by critical enquiry and provocative arts practice. We can contribute to the necessary socioeconomic transformation by telling stories of times and places where people live, and lived, rich lives under conditions of material simplicity. Examples come from history, from archaeology and from many places in the contemporary world.

None of this is easy. It may not be quick enough. Some of us will need to chain ourselves to trees, as Andrea Gaynor has done. But if we are ‘the privileged predecessors speaking from this side of extinction’, to use Tom Ford’s words that think the unthinkable, what is the alternative?