This article is based on Dr Emma Cole’s 2024 Trendall Lecture, Experiencing immersion from antiquity to modernity, presented at the Australasian Society for Classical Studies Conference (ASCS) in February 2024. The full video of her lecture can be viewed at the end of this article.

Immersive experiences are big business within today’s creative economy. Forms range from analogue museum and theme park experiences, such as the Bluey’s World to open in Brisbane in August 2024, through to the digital mediums of virtual (VR), augmented (AR), and mixed reality (XR). Although the rhetoric surrounding immersive experiences would have you believe that these are innovative undertakings, the idea of immersion is not a new phenomenon. Paintings, sculpture, and theatre have all been theorised historically in terms of illusion, realism, and immersion, and textual critics in antiquity also theorised literature’s ability to create the sensation that a reader or a listener was present at the events being described.

What might we learn from putting immersion, ancient and modern, side by side? And what are the most promising routes for collaboration between researchers and third-sector organisations on future immersive experiences?

Immersion and influence: powerful or ‘corrupting’?

Immersive experiences can be defined as experiences that displace one from their present reality, engulf one’s senses, and encourage one to feel and/or think differently. Experiencing immersion is not necessarily an all-or-nothing state, but rather, as Rose Biggin argues, are graded, fleeting, and temporary experiences defined by an awareness of their temporal and spatial boundaries.

Critics in ancient Greece were both fascinated by and fearful of experiences which might encourage such sensations. Plato, for example, was concerned by the power of art to facilitate instances where a theatre audience might find themselves unable to distinguish between appearance and reality.

In The Republic, Plato argued that mimetic art risked facilitating a close identification between a listener and a character, which could have a corrupting influence upon the soul of a listener when a character is depicted as engaging in immoral behaviour. The conjuring of a hyper-realistic, alternate reality risked influencing one’s habits and shaping their soul.

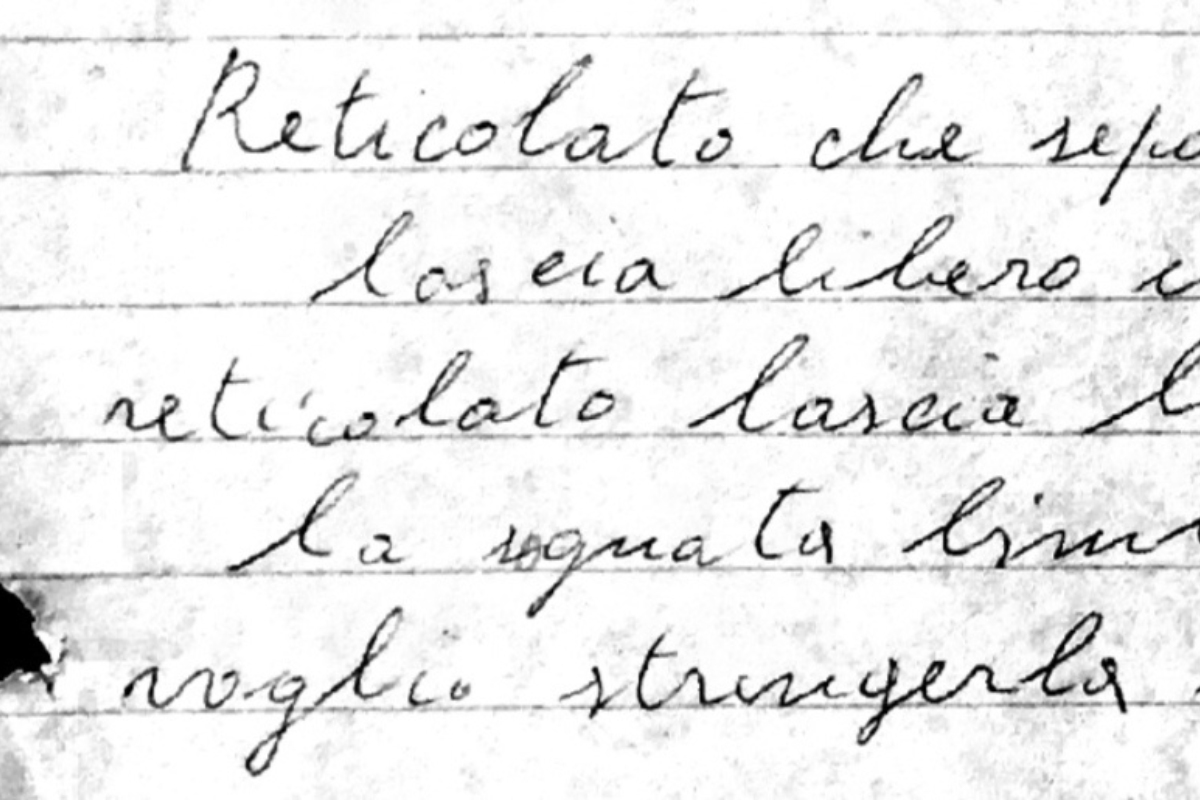

Although Plato’s consideration of mimesis focused on the dangers that immersion represents to humanity, many others in antiquity celebrated those techniques which drew in viewers, listeners, and readers. Narratives going back to Homer’s Trojan War epic The Iliad were renowned for their ability to create the sensation that a reader or listener was present at the events being described. The ancient Greeks even had a specific term for passages that facilitated this sensation: enargeia, meaning vividness.

‘Making imagining feel like doing’

Enargeia was defined by Dionysius of Halicarnassus as the power of ‘bringing the things that are said before the senses of the audience’ and enabling the audience to feel as if they ‘can see the actions which are being described going on and that they are meeting face-to-face the characters in the orator’s story’. Such passages could affect one emotionally, had a time-warping function, and also had a sensory dimension, making imagining feel like doing, and inviting an embodied response.

Ancient critics identified enargeia not only in Homer’s Iliad, but across a vast range of ancient poetry and prose. We find enargeia, for example, in ancient law-court speeches, such as Lysias 1. Here the accused, Euphiletos, defends himself for murdering his wife’s lover and utilises energeia to immerse judge and jury within his version of events so that they have no option but to acquit. We also find enargeia in ancient historiography, where Thucydides’ narration of a doomed expedition positions the readers as spectators, watching the Athenian defeat at Syracuse from the shore. Plutarch described this passage as so like the actual event that the representation became indistinguishable from reality, with the reader able to experience the exact same emotions as those at the event.

Bluey’s world: a modern synergy

There is a difference in directionality when it comes to the ancient understandings of immersion, and our modern experiences.

In the former, the imagined world enters our contemporary moment, while in the latter, we step into the other world. Yet the effect of both experiences is in synergy. Just as Bluey’s World is predicated on a desire for today’s children to experience, well, Bluey’s world, so too did the ancient experiences that brought myth, history, and even crime to life stand out as noteworthy precisely because they enabled one to experience an alternate reality.

The preoccupation with feeling like one has a first-person experience of a time, place, or story is a transhistorical urge. Historicising immersion reminds us to be cognisant of the ethics of immersivity, and not to be sniffy about the proliferation of experiences that are now being deemed immersive. And it is in the intersection between antiquity and immersivity where we can find perhaps the greatest opportunities for academic and creative collaboration on new experiences. The use of VR within the Australia Museum’s Ramses exhibition, the immersive classics-based video games such as Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey, and the Greek tragedy-based immersive theatrical experiences of companies such as Punchdrunk, about which my latest book Punchdrunk on the Classics investigates, all show the mileage to be found through this connection.

Borrowing the stories and techniques used to facilitate immersion in antiquity, and combining them with the technologies of today, holds countless opportunities for the future.

Stream the 2024 Trendall Lecture