In Ukraine, evidence has been collected in Bucha and Mariupol and elsewhere of ill-treatment of prisoners, theft, and needless destruction of cities and of supplies necessary for civilian life, like food and water. The latest violence in Sudan raises the prospect of yet more African prosecutions before the International Criminal Court.

The issues seem straightforward: civilians and surrendered personnel have been gravely mistreated and sometimes killed, and justice should be done. Sandra Wilson FAHA and Robert Cribb FAHA look to the past to help us understand the complexities involved in prosecuting war criminals.

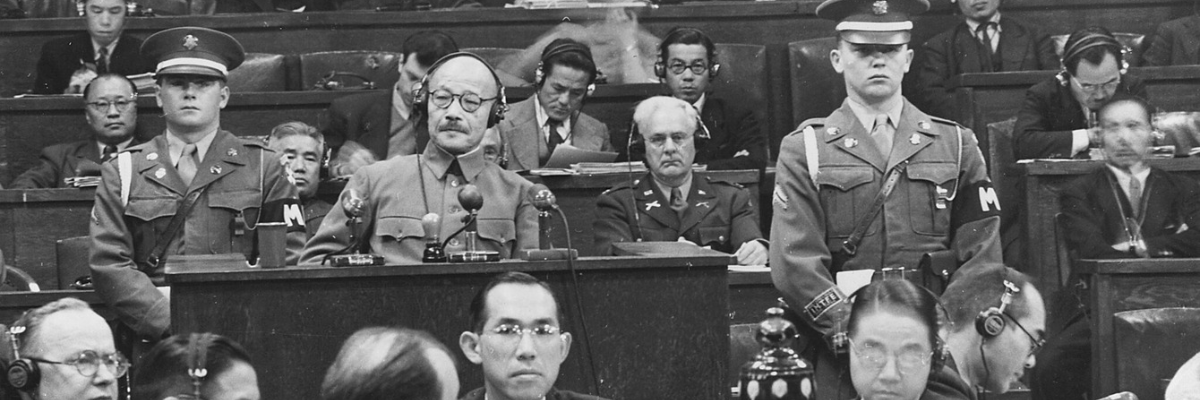

Today’s model for war crimes trials was set in the late 1940s after the end of the Second World War, when the victorious Allied powers embarked on a program of reckoning with their defeated adversaries.

The basic principle was to hold accountable the individual perpetrators of crimes, rather than the countries or institutions to which they belonged.

The proceedings against Nazi war crimes suspects in Nuremberg are well known. In Tokyo, the International Military Tribunal for the Far East prosecuted Japanese civilian and military leaders. In addition, thousands of military personnel of all ranks were prosecuted in national military tribunals in about 50 different venues around the Asia-Pacific region, including Darwin, Rabaul, Singapore, Kuala Lumpur, Hong Kong, Manila and Manus Island. Prosecutions stretched between 1945 and 1951, and Australia was a key player.

The circumstances of war in the middle of the 20th century differ from those of the first two decades of the 21st century. Yet, the crimes in the two eras are strikingly similar, and the impetus to hold trials is the same: wrongdoers should be punished.

The earlier war crimes trials, however, contain some clear lessons for authorities contemplating new proceedings.

Three lessons stand out:

Lesson one: it’s harder than you might think

The first lesson is that prosecuting suspected war criminals is an extremely difficult undertaking, no matter how straightforward the issues might seem to be.

Witnesses may be dead or otherwise unavailable or unwilling to talk. Recollection of events that had occurred in the heat of battle, perhaps long before, can be uncertain. Documents may have been destroyed or lost. Crime scenes will have been disturbed.

In the 1940s, prosecutors were able to rely on expedited procedures, including mass trials and proceedings as brief as a few hours. Courts accepted hearsay and other unreliable evidence. These shortcuts are unlikely to be acceptable today.

Lesson two: it’s difficult to figure out who should be held responsible

A second lesson is that questions of military hierarchy will always dog war crimes trials.

Allied officials planning for trials in the Pacific were determined to avoid prosecuting only the most junior soldiers who actually carried out, for instance, illegal executions. They wanted to reckon also with those who had issued the orders and those who had failed to take steps to prevent their subordinates from committing atrocities.

To deal with this issue, the tribunals developed the doctrine of command responsibility, under which officers could be held responsible for the actions of their troops.

A very large number of the Allied convictions of Japanese defendants were based on this doctrine.

The principle seemed straightforward. But in practice, command responsibility proved to be uncertain and ambiguous.

Many commanders were found guilty of the crimes of their subordinates, but it was difficult to decide how far up the chain of command it was necessary to look for culprits. Even when commanders were found guilty of the crimes of their subordinates, junior personnel, who may have committed war crimes in challenging circumstances, were generally not exonerated.

Lesson three: Law should not be prosecuted only by the victors

A third lesson is that one-sided prosecutions are a recipe for trouble.

In the late 1940s, international law did not permit the prosecution of Allied soldiers for any of the actions with which Japanese and German soldiers could be charged, most notably the killing of surrendered prisoners, a crime committed by all sides.

Japanese defendants were prevented from raising in court offences committed by the Allies. Allied soldiers could be prosecuted only under their own military law, but such prosecutions were very rare.

Moreover, at the very same time as Japanese military suspects were being tried, or shortly afterwards, Western colonial soldiers were fighting nationalist revolutions in Asia. In these conflicts they used many of the same techniques – arbitrary killing, torture, detention in appalling conditions – for which Japanese soldiers were being prosecuted.

No Western colonial soldiers fighting nationalist revolutions in Asia or Africa, however, were held accountable for these crimes.

The one-sidedness of the prosecutions gave rise to the powerful accusation that the trials constituted ‘victors’ justice’ rather than an impartial application of principles of legal reckoning. This perception seriously undermined the legitimacy of the trial process, especially in later years.

Convinced that they had fought a ‘good war’ against Japan and Germany, Allied leaders did not envisage prosecutions of perpetrators on their own side in the 1940s. Nonetheless, they were explicit that the standards they had set in the post-1945 trials would apply to everyone, presumably including their own heirs, far into the future, ideally forever.

Nothing worth doing is ever easy

As it turned out, however, war crimes prosecutions did not resume until the establishment of the 1993 International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia and the 1994 International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda.

There was no formal reckoning for atrocities committed during the many wars of the intervening period, including in Korea, Vietnam, India, Pakistan and Iraq, in part because of the difficulties that had been encountered in the trials held in the 1940s.

Australia, as an enthusiastic participant in the war crimes trials process after 1945, eventually committed itself to applying international law, not just to enemies but also, where necessary, to its own soldiers. Problems of evidence and the complexities of command responsibility mean that Australia’s commitment will be difficult to uphold.