Translation helps us to see things from different angles. As individuals and as nations, we plainly have a critical need for that kind of insight.

Milan Kundera, in his personal essay on the novel, The Curtain, first published in French in 2007, argues that works of art can be understood in two fundamental contexts: the ‘small’ context of the nation and the ‘large’ context of the world, encompassing the supranational history of art forms themselves. Provincialism, Kundera argues, is the inability to imagine one’s national culture in the large context.

He thinks provincialism has done great damage to our understanding of literary history:

. . . if we consider just the history of the novel, it was to Rabelais that Lawrence Sterne was reacting, it was Sterne who set off Diderot, it was from Cervantes that Fielding drew constant inspiration, it was against Fielding that Stendhal measured himself, it was Flaubert’s tradition living on in Joyce, it was through his reflection on Joyce that Hermann Broch developed his own poetics of the novel, and it was Kafka who showed García Márquez the possibility of departing from tradition to ‘write another way’.

The entire history of literature, it might be argued, is informed by a process of transmission; a great work of literature, indeed any text, is able to enrich itself by generating new meanings as it enters new contexts. Kundera continues,

[G]eographic distance sets the observer back from the local context and allows him to embrace the large context of world literature, the only approach that can bring out a novel’s aesthetic value. . .[1]

Translation can be seen in this perspective as the secret metaphor of all literary communication.

But the way the English-speaking world views translation remains quite negative, despite everything that has been written by theorists, authors and translators themselves. The most common misconception is that translation always entail loss. There are the publishers, of course, who seem to see translation as an essentially mechanical process and who offer contracts that reflect that view. And reviewers who, strangely, appear not to notice that the work under review is a translation or, when they praise a translated ‘author’s’ style, usually fail to acknowledge that the writing is actually the translator’s.

One way to redress the view that translation is inherently inadequate is to foster a clearer appreciation of the fact that every translation of a text is a performance of that text. The performance is reflected in the selection and sequence of words on a page. If we can appreciate the dimension of performance in relation to music or theatre, why not also in relation to translation?

Translation is a kind of performance art that combines close reading and creative (re)writing. It’s an art of imitation: a quest to reproduce a text’s ‘voice’. This involves a multiplicity of exact choices concerning rhythm, register, sound, syntax, tone, texture: all those things that make up style and reflect the marriage between style and meaning.

Finding Proust’s voice

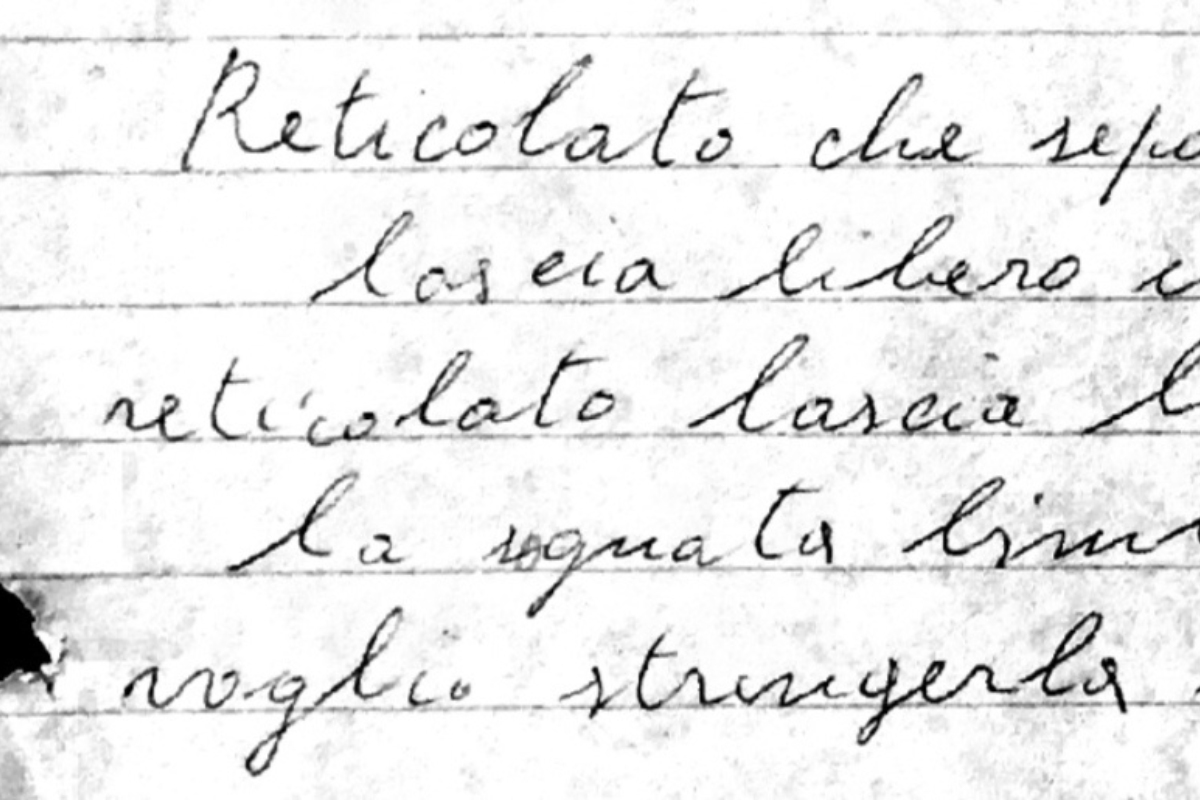

In my recent translation of the first volume of Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, The Swann Way, I strove, of course, to recreate Proust’s style.

His style is closely identified with his famous long sentences, with their coiling elaboration. As they uncoil, the sentences express the rhythms of a sensibility, the conflicts and convolutions of a mind that forms the framework – indeed the subject-matter – of the narrative as it unfolds, via many detours and with a dynamic backward- and forward-looking movement, from childhood beginnings to mature adulthood.

The narrative builds multiple perspectives into a symphonic structure, promoting a dramatic narration as the narrator comes slowly to understand the significance of his past life.

The Proustian sentence reflects the narrator’s exploration of his experience, presenting things as he sees them and reflects upon them. Thus, it is vital to deal effectively with the twists and folds, the carefully modulated rhythms and shapes, of Proust’s sentences. Style is vision; if you don’t get the style, you miss the vision.

Why translation matters

To the extent that we recognize the skill and creativity involved in literary translation, we will have more translations, even better translations and a better literary culture. We return to Kundera’s point. It goes to the heart of the enterprise of literature itself. Literature is enriched through the agency of translation.

The case for translation in these terms was made compellingly by Susan Sontag in her 2002 St Jerome Lecture on Literary Translation. Her essential argument was that a proper consideration of the art of literary translation is a claim for the value of literature itself.

My sense of what literature can be, my reverence for the practice of literature as a vocation, and my identification of the writer with the exercise of freedom – all these constituent elements of my sensibility are inconceivable without the books I read in translation from an early age. Literature was mental travel: travel into the past and to other countries. Literature was the vehicle that could take you anywhere.[2]

And yet, relatively speaking, English translates very little. Less than 3% of works published in the English-speaking world are translations, whereas the corresponding figure for a country like Sweden exceeds 50%.

That dismal percentage, less than 3%, is fraught with dangers of impoverishment: a restricted vision of the world, consolidation of the global domination of English, acceleration of the dwindling number of world languages taught, and encouragement of non-anglophone cultures to write in English in order to be heard by the rest of the world.

[1] Milan Kundera, The Curtain (London: Faber and Faber, 2007), pp. 35-36.

[2] Susan Sontag, ‘The World as India’, in At the Same Time: Essays and Speeches (London: Hamish Hamilton, 2007), pp. 156–79 (p. 179).