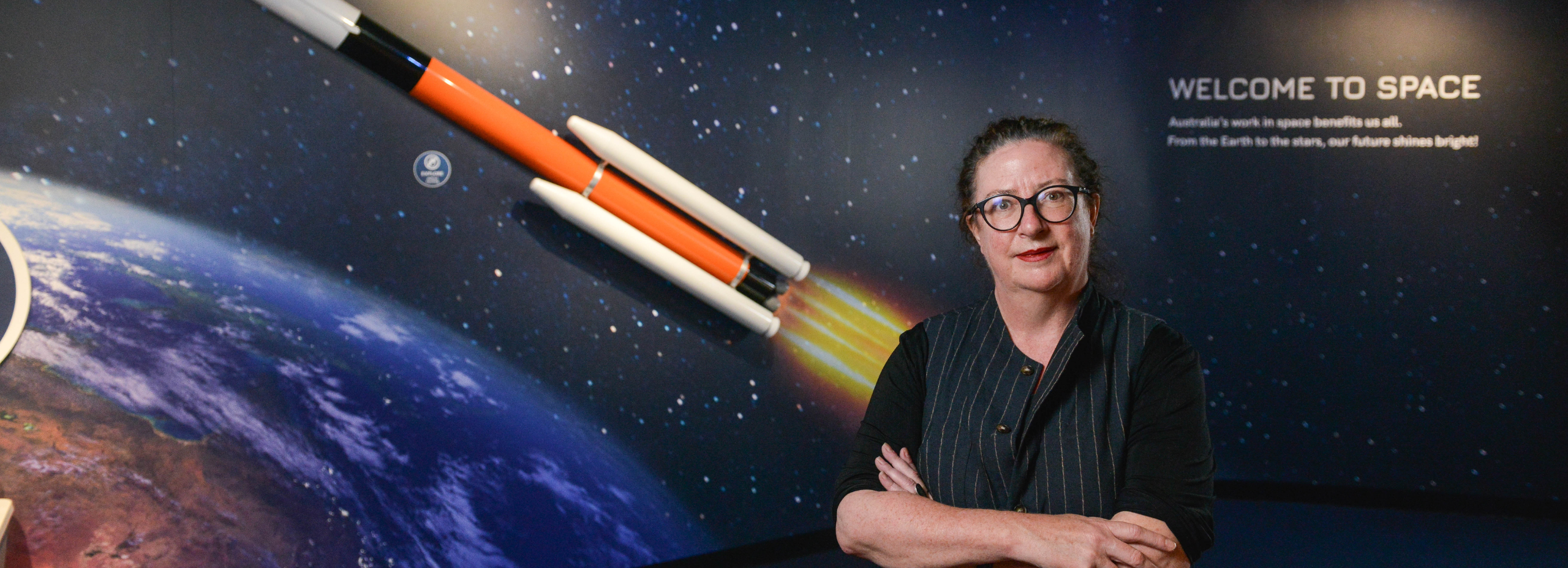

‘Why are you here?’ It was one of the first questions space archaeologist, Associate Professor Alice Gorman FAHA FSA, remembers being asked at a space industry conference in Canberra back in 2003.

Alice can still recall the mix of surprise and confusion her paper received. ‘People asked me “why are you here?” even as I was trying to explain why we needed to think about archaeological records in space and the cultural significance of those artefacts.’

Humans have been leaving remains in space since the 1950s but space archaeology — the study of human-made materials beyond Earth and their relation to humanity’s exploration of space — was a new idea in the early 2000s. It was also a far cry from Alice’s established work in Indigenous archaeology and cultural heritage.

‘I knew I wanted to devote everything to researching space archaeology. I’d resigned from my role as a heritage consultant, so when I came back from the 2003 World Archaeological Congress in Washington DC, I had no job, nowhere to live. I’m not ashamed to say I moved back with my parents — and I started going to Australian space events.’

A ‘suitable’ career for a rural girl

Growing up on a farm in rural Australia, Alice recalls late nights with her dad who would point out constellations in the night sky and talk about the ancient myths the stars inspired.

‘One day, a travelling salesman turned up selling encyclopedias and Dad invited him in for a drink. A few homebrews later, Dad had bought not one set but multiple sets of encyclopedias. From there I was entranced reading about the solar system, Earth, human evolution, Greek mythology, and Roman history.’

While at high school in her regional town in the mid 1970s, Alice recalls she was set on studying archaeology and astronomy from an early age while her teachers were encouraging students to consider a ‘suitable’ career for a woman such as nursing or teaching.

‘I wanted to be both,’ Alice says. ‘But there was a time when I knew I had to choose.’

When she felt she didn’t get the marks in her physics exam to study astrophysics, Alice chose archaeology. Later in life, she’d realise she scored the same marks as one of her male colleagues, who had gone on to become an astrophysicist.

A bolt from the blue

After graduating with a Bachelor of Arts with Honours from the University of Melbourne, Alice began consulting in the field of Indigenous heritage management and obtained her PhD at the University of New England in 2001.

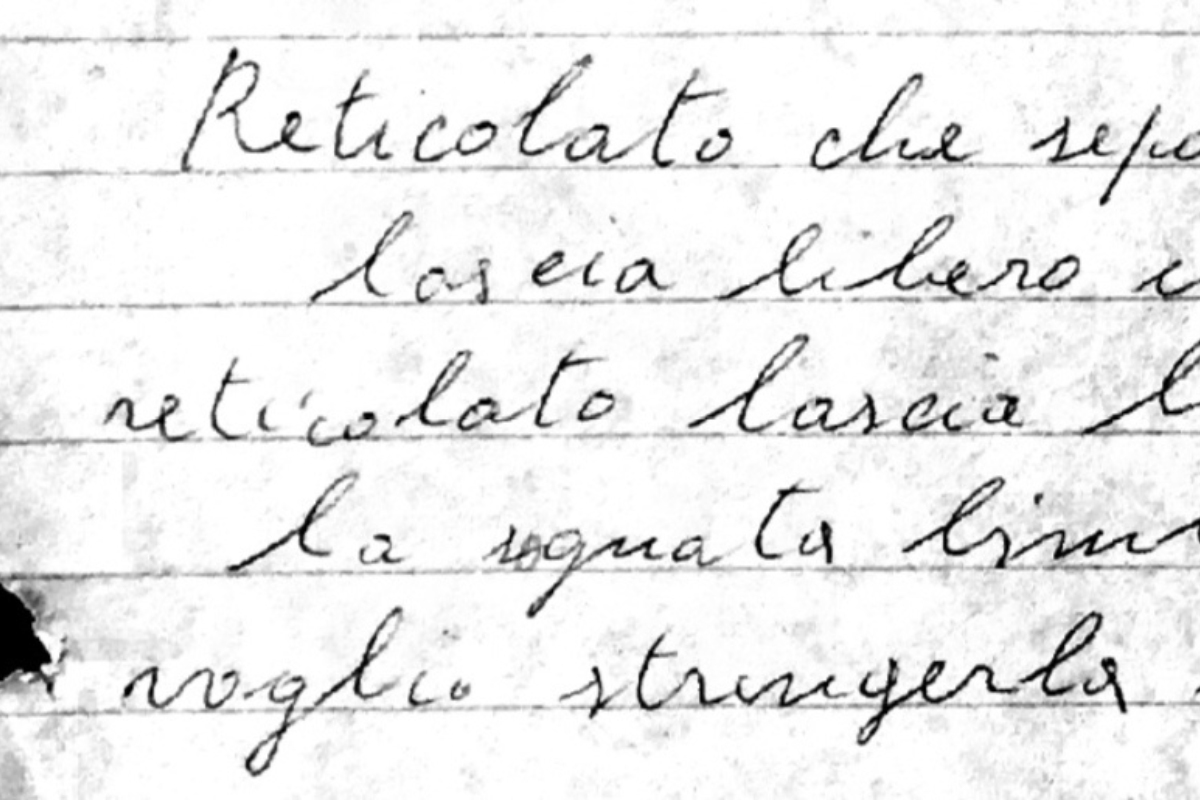

Her doctorate examined how archaeologists could identify tools used in body modification to provide evidence for symbolic behaviour in humans throughout antiquity. If you could pinpoint the time period when humans and their ancestors started using their bodies to express symbolic meanings, then you were one step closer to identifying the origins of language.

‘I was in my mid-thirties, and I was quite established in my career and consulting on various jobs on Indigenous heritage and archaeology throughout Queensland and NSW.’

One night, in the very early 2000s, Alice describes she had a ‘bolt from the blue’, and everything shifted.

‘I was sitting on the veranda enjoying a beer when I saw a satellite, and I just thought, “oh my god. I’m looking at human-made objects and space junk. That is an archaeological record.” At that moment, I knew that was my passion.’

What is a space archaeologist?

Alice recalls, with a laugh, that she spent every night researching and ‘getting up to speed’ with space history, doing as much research as her rural dial-up internet could handle.

She began researching the Vanguard 1 satellite — the oldest human-made object in orbit — and the Woomera launch site, combining her experience in heritage archaeology with her growing interest in space by researching the impact of launch sites on displaced Indigenous communities.

But it wasn’t until she attended the annual Australian Archaeological Association conference in Townsville and was introduced to Professor John Campbell, who was also exploring the field of space archaeology, that the dial shifted cosmically.

‘He told me he was running a session at the World Archaeological Congress in Washington DC and encouraged me to submit a paper. I ended up submitting two — both on my research on space archaeology — and they were both accepted. So, I went!’

Telling the story of humanity in space

After returning from Washington DC, Alice says she “became invested with doing the legwork” to develop the profile of space archaeology.

‘I began turning up to events and I’m sure people said, ‘oh there’s that strange archaeology lady again’ but I didn’t go away.’

‘One thing I dedicated myself to was learning the technical space literature. I knew I needed to know the tech stuff so I could speak the same language as the aerospace engineers,’ she says. ‘Now, I can be at a space conference or meeting and people won’t know I’m an archaeologist unless I tell them.’

Alice credits her humanities background as the vehicle to develop the skills she needed to communicate across disciplines as a space archaeologist.

‘Eventually, all that tech stuff became understandable, but it was my humanities background that helped use it to tell a story and develop the field of space archaeology further.’

‘I became a member of associations and began talking about the general field of space in Australia, not just space archaeology. Then, I started joining committees and things started to shift.’

In 2011, Alice became the first woman elected to the Advisory Council of the Space Industry Association of Australia (SIAA) — the national peak body for the Australian space industry. The SIAA’s successful bid to host the International Astronautical Congress in Australia in 2017 helped pave the way for the establishment of the Australian Space Agency, an achievement Alice is quick to add she, ‘only played a small part in.’

Now, if there’s a space event and Alice isn’t there, people notice.

Working in space & the artefacts we leave behind

‘People are not just interested in my heritage work and my background in archaeology,’ she says. ‘But they’re also interested in my broader philosophical approaches and opinions about the way we work in space, and what to do with the cultural artefacts we leave behind.’

‘Sometimes, I can be the only person in the room with a humanities background and I’ll say things that I don’t think, as a humanities scholar, are particularly remarkable but they’re aspects that my colleagues, who are mostly engineers, simply have not considered. That input is highly valued.’

In 2021, the International Astronomical Union named an asteroid orbiting between Mars and Jupiter in Alice’s honour, recognising her incredible contribution to the field of space research internationally. In 2022, she co-directed an archaeological survey on the International Space Station, which was the first archaeological fieldwork ever to take place outside Earth.

She is a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries in London, has her own episode of Alie Ward’s podcast, Ologies, about becoming a space archaeologist and in 2023, was named a Fellow of the Australian Academy of the Humanities.

She also shares a connection with another AAH Fellow. Biographer Brenda Niall, who was elected in 1990, is Alice’s cousin.

‘She was delighted with my election and sent her congratulations. I’m so pleased to join Brenda in the growing number of women elected to the Fellowship, and to continue the good fight the Academy fights in promoting the humanities in Australia. My background is in the humanities, and humanities training in general is something I know is essential understanding our past, present and future. It’s eroded at our own peril.